What happened to the landscape and people during the Stone Age flood disaster in Eastern Norway?

Around 10.000 years ago, a ‘plug’ in the ice barrier in a massive glacial lake loosened, causing a megaflood to sweep through the landscape. Scientists are learning more about exactly what happened during this catastrophic event.

Geologists have, since the end of the 19th century, suspected that a great flood swept through the landscape in Eastern Norway at the end of the last ice age.

It created strange geological phenomena and left traces that have now enabled scientists to establish not only that the megaflood indeed took place, but also what it did and how it fared through the landscape.

“We’ve now taken a closer look at the large areas that were flooded in Eastern Norway during the flooding calamity,” geologist Fredrik Høgaas says. “We also think we know exactly when the flood occurred.”

Formed Jutulhogget canyon

In 2021, Høgaas and his colleagues presented new findings about the megaflood.

The flood that happened during the Stone Age, some 10 000 years ago, turned out to be even bigger than scientists had previously assumed.

The huge masses of water managed to create the mighty Jutulhogget canyon between Østerdalen and Rendalen in a matter of only a few weeks.

But what happened when the megaflood reached today's densely populated areas further south in Eastern Norway?

Eight researchers associated with the Geological Survey of Norway (NGU), the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) and the County Government of Innlandet took a closer look at this in a new study.

Tail end of the Ice Age

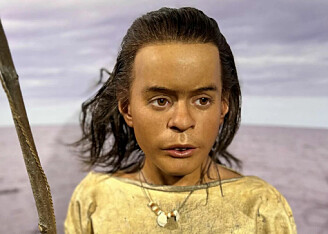

Stone tool findings indicate that the first people might have settled in Norway at least 11 000 years ago.

This was right after the Ice Age ended.

The people who had survived in Southern Europe during the Ice Age began to increase in number and spread out over a much larger area.

People probably came to Eastern Norway in boats through a protective archipelago in today's southern Sweden. People might also have come from the east.

When the megaflood hit Eastern Norway, people had lived here for about a thousand years.

Giant lake outburst

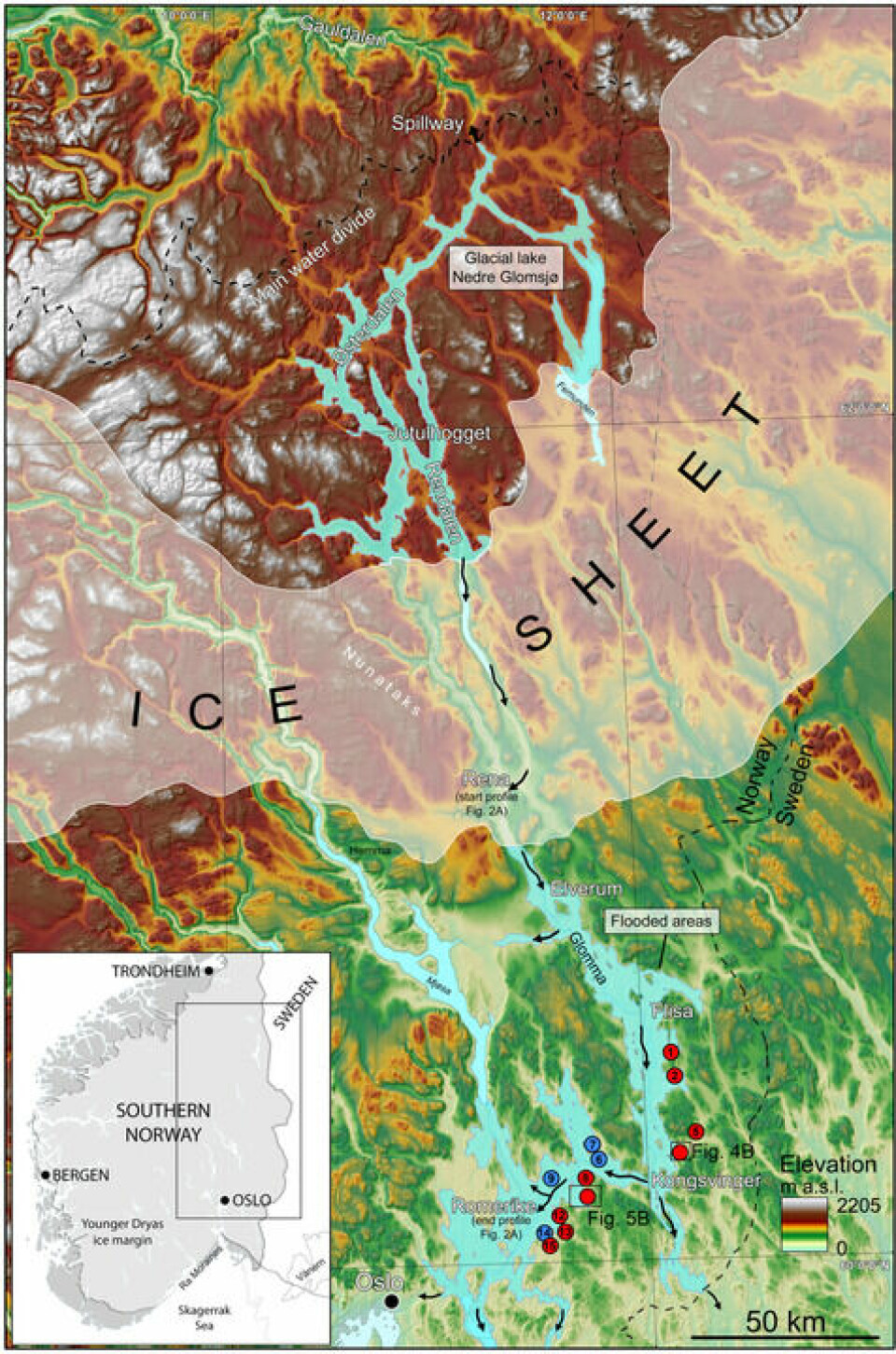

It was the gigantic lake called Nedre Glomsjø – with a volume twice as large as today's lake Mjøsa – that suddenly burst through an enormous glacial cap.

The glacial cap that dammed Nedre Glomsjø stretched almost all the way to Elverum, where the outburst flood drained out.

The water gushed down Østerdalen towards Eastern Norway.

Icebergs were carried downstream, and some became entrapped and ploughed deep furrows in the clay plains around the village of Vormsund.

At Romerike, the terrain is quite flat, and here the water spread out in what was then an ocean bay.

The water level rose a ‘mere’ 35-40 metres.

A sea level rise of 55 metres

Towards Kongsvinger in the east the flooding was even more powerful.

Here the water raged up to 85 metres above the valley floor, according to findings Høgaas and his colleagues now believe they can confirm.

“We believe that the sea at that time was approximately 170 metres above today's sea level, which means that the catastrophic flood led to a temporary rise in sea level of 55 metres!”

“At the same time, huge amounts of gravel, sand and mud were washed out over the landscape,” says Høgaas.

A wasteland of mud

A few days later the floodwaters were gone.

“The water level was the same as before the flood. But it left behind a wasteland of gravel, sand and mud,” says the geologist.

For the past two years, Høgaas and his colleagues have been taking a closer look at the destruction wrought in the areas of Eastern Norway that were inundated by the flood.

“If you dig into the ground in Romerike a little, in a lot of places you’ll find a characteristic light layer of silt that is called Romeriksmjele in Norwegian", Høgaas explains.

Mjelen or mjela refers to the silt bed remains after the flood, Høgaas informs us. Silt is fine sand, dust-like but solid, which has been transported by water or ice and been deposited as sediment.

The Romerike Silt Bed is up to 1.5 metres thick.

Mapped the silt bed

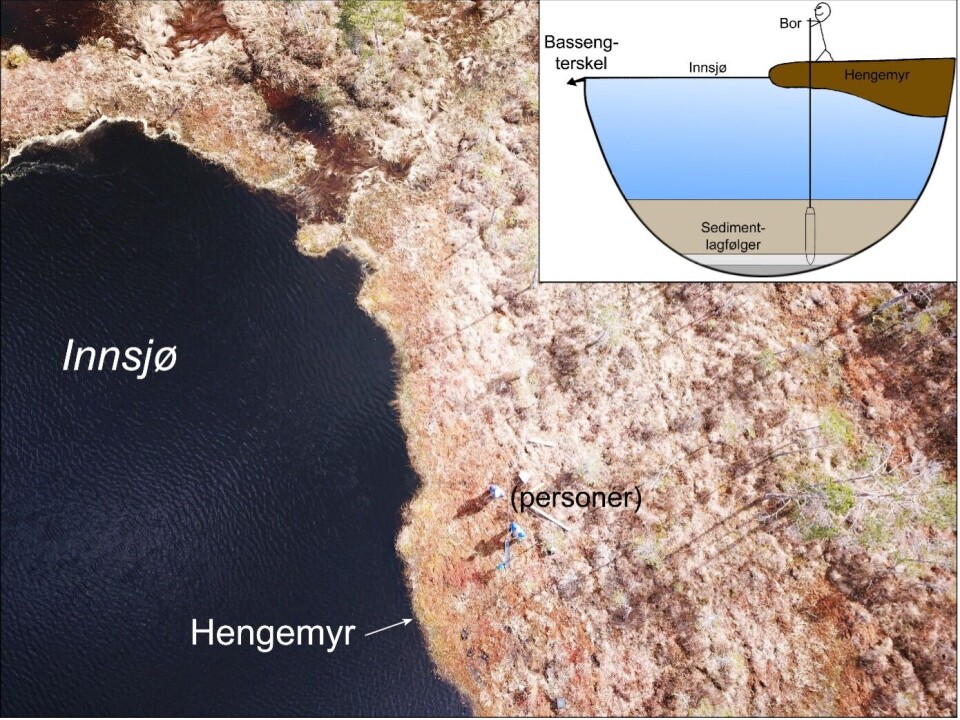

The geologists have now been able to precisely delineate the areas that were flooded by the megaflood by using the distribution of the sediment records in this silt bed.

They traced the silt bed upwards along the sides of the impacted terrain by examining sediments in the depressions.

Høgaas says that lakes and marshes acted as natural "sediment traps" during the megaflood.

“At the bottom of these water beds we found a lot of sediments from the flood.”

“We worked based on the principle that the sediments carried by the masses of water were deposited up to a certain elevation in the landscape. This height reflects the peak flooding, and no trace of the flood sediments are found above that.”

In this way, the researchers have been able to infer the maximum flood level from the terrain.

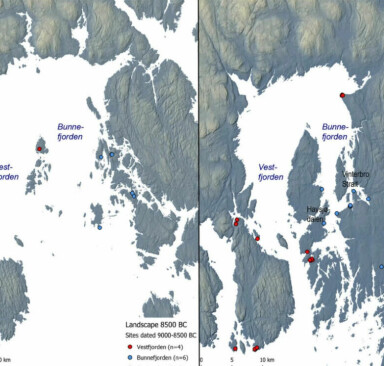

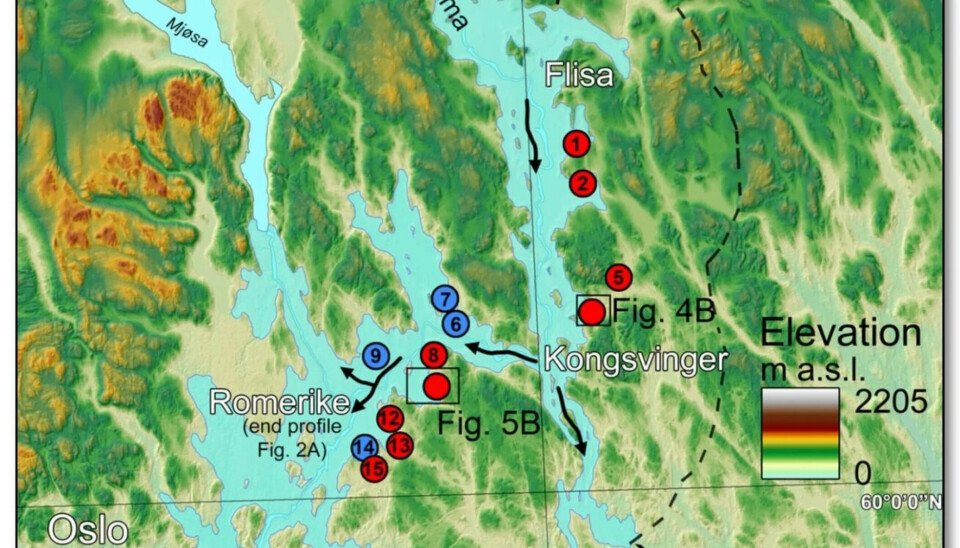

They have also been able to reconstruct just how large the flooded areas were, as shown on the map below.

Catastrophe happened 10 400 years ago

The red circles on the map show places around Flisa, Kongsvinger and on Romerike where geologists have collected sediment samples from lakes and marshes.

“Around Kongsvinger, the catastrophic flood reached 225 metres above today's sea level.”

“At Romerike, the area was flooded up to 190 metres above sea level.”

The researchers also sifted through the sediments in search of birch bark, leaves and other ancient organic material from before and after the flood. These have been dated using the radiocarbon method.

“The dating shows that the catastrophic flood from Nedre Glomsjø occurred around 10 400 years ago.”

Thick mud put a lid on Eastern Norway

Høgaas notes that the flood must have had enormous environmental consequences.

A thick layer of mud settled like a lid over the whole of this large landscape in Eastern Norway.

“In some places, the lid might have been several metres thick. Elsewhere it was thinner. In any case, it must have led to huge destruction.”

“Enormous areas were affected. Marine ecosystems were destroyed, and for shore-bound indigenous people who harvested from and were completely dependent on the sea, the consequences were no doubt tremendous,” Høgaas says.

“And then we have to consider the psychological perspective in a superstitious society. Who wants to live in a place that’s constantly hit by natural disasters?”

What were the people thinking?

Høgaas speculates whether the Stone Age people might have left parts of this area following the disaster.

Both Romerike and much of the land around the Oslofjord could have suddenly become much less attractive places to live.

Even several years after the Nedre Glomsjø disaster, people might have been forced to settle elsewhere in Eastern Norway.

Icebergs from Østerdalen far out to sea

The flood had an enormous reach.

In the 1920s Swedish geologists believed that a thick layer of silt mapped north of Lake Vänern was due to the draining of Nedre Glomsjø.

“And in studies of marine sediment cores from the Skagerrak, a special layer with a striking amount of sand and gravel has been linked to the melting of giant icebergs that were transported far out to sea during the event.”

The Skagerrak strait runs between the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, the southeast coast of Norway and the west coast of Sweden.

Høgaas suggests that the flood sediments will be able to serve as a well-dated "event marker" in the sedimentary sequences in Eastern Norway and in the surrounding areas.

Reference:

Fredrik Høgaas et.al.: Timing and maximum flood level of the Early Holocene35 glacial lake Nedre Glomsjø outburst flood, Norway. Boreas, 2023.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------