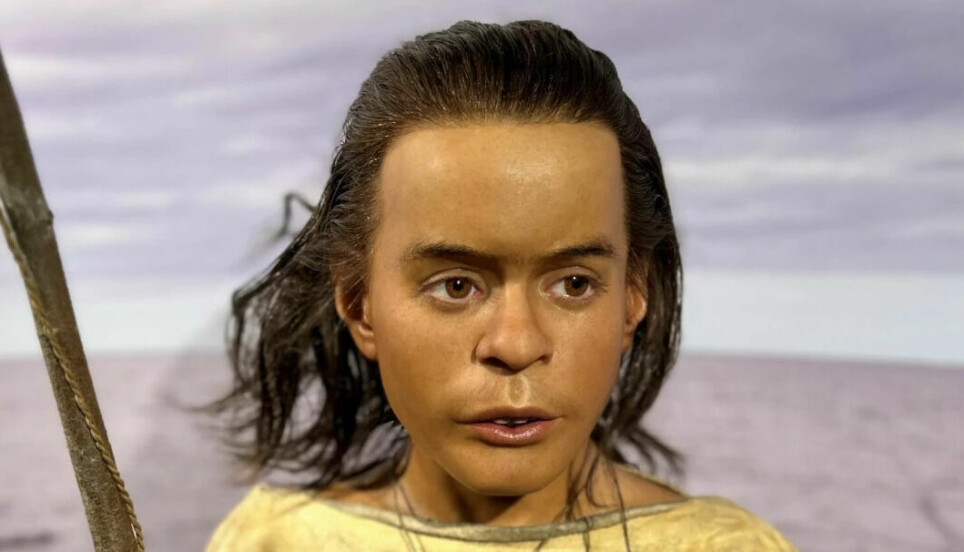

This is what a Norwegian boy looked like 8,000 years ago

The Stone Age boy has now been reconstructed using DNA analysis and modern forensic techniques.

Researchers do not know why Vistegutten – the boy from Viste – died at only 14 years old. He was apparently healthy.

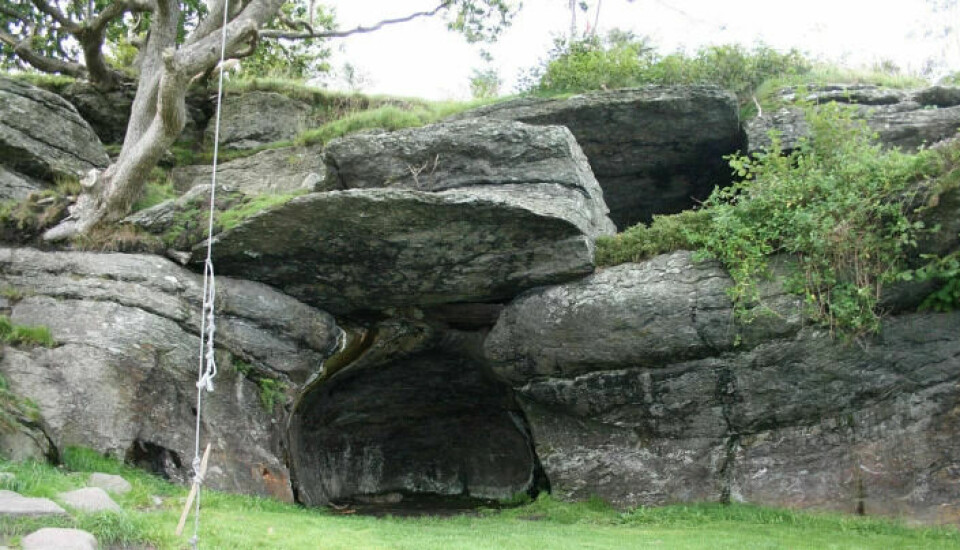

He was buried in the small Vistehola, a cave located a little north of Stavanger in southwestern Norway. The same little cave that his parents may have lived in.

He is the best-preserved person from the Stone Age in Norway.

Reconstruction of the boy

“I spend most of my day working with skeletons of ancient people,” archaeologist Sean Denham at the Museum of Archaeology in Stavanger says.

“But seeing a living person in front of me in this way is something completely different. Oscar Nilsson has done a fantastic job with this new reconstruction.”

Denham is also happy about the increased interest in the Stone Age in Rogaland and Norway that the museum, in collaboration with sculptor and archaeologist Nilsson, has now managed to achieve with this reconstruction.

Fish and nuts

It was during an archaeological excavation of Vistehola in 1907 that researchers found the boy's remains.

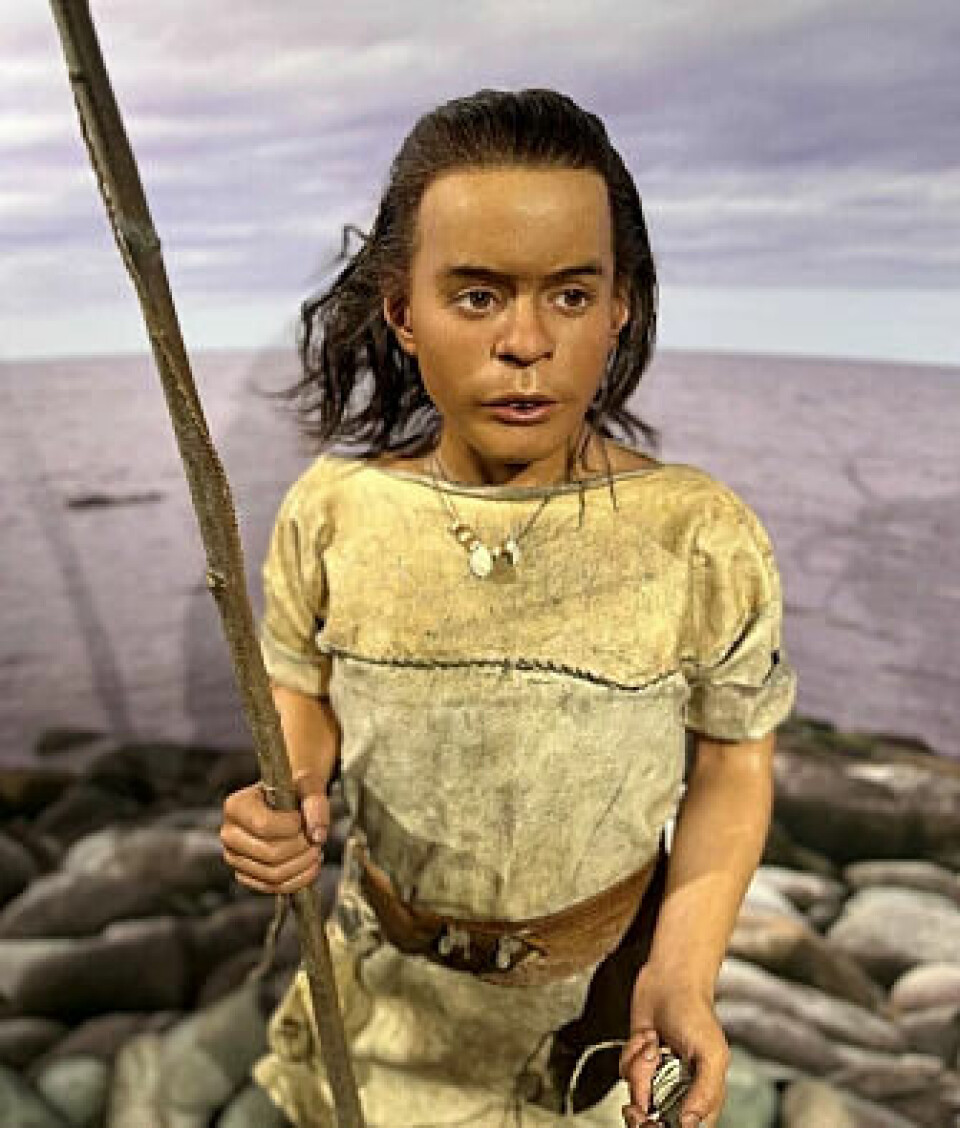

He was only 125 centimetres tall.

With the help of new research methods, the researchers know that the boy has eaten as much food from the sea as from land. Cod, seal, and wild boar were on the menu for those who lived near the beach at Jæren. So were shellfish and nuts.

Even for a Stone Age man, Vistegutten was small in stature. Adult men from the Stone Age in Norway were probably 165-170 centimetres tall. The women may have been 145-155 centimetres tall.

Both sexes had strong physiques, the signs of which can be seen in Vistegutten as well. Eyes and cheekbones were often quite prominent in people in Norway at the time.

The boy was probably fairly dark-skinned.

Face shape, skin and hair

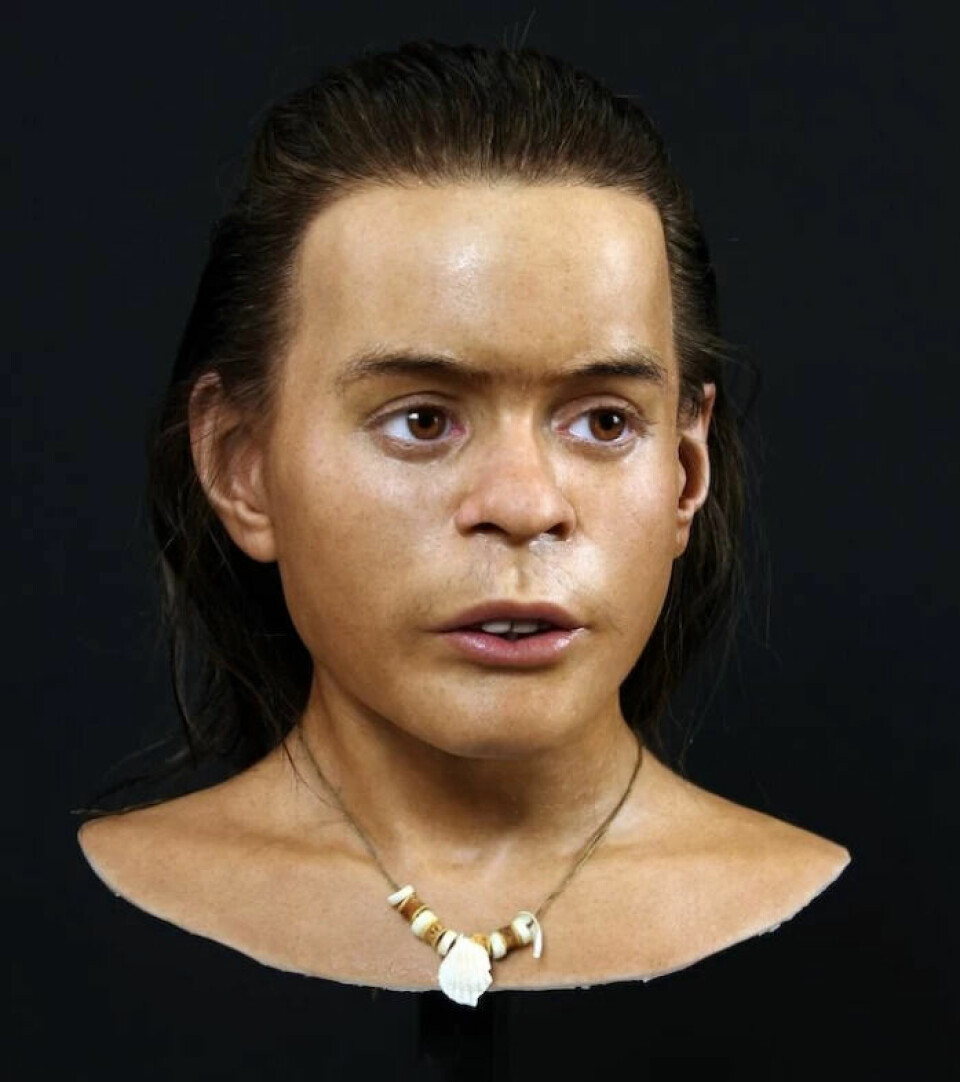

“For a while there was some doubt about whether this was a girl or a boy. But with the help of DNA analysis, we can now say with certainty that Vistegutten was a boy,” Denham says.

The reconstruction Oscar Nilsson has made is based on DNA analysis. It also builds on a project from 2011, where researchers at the University of Dundee in Scotland scanned the skull of Vistegutten with a laser, and created a 3D model of his head.

“The DNA analysis that was carried out later, tells us more about the shape of his head,” Denham says. “We are a little more uncertain about his skin colour, hair colour, and the colour of his eyes. So here we rely on the other finds we have of Stone Age people in Norway.”

The average lifespan in the Old Stone Age was not very high. This was largely due to the fact that so many young children died. When people first reached adulthood, it was not unusual for them to live to be over 50 years old.

We don't know why Vistegutten died so young.

Sources:

Norgeshistorie.no, Wikipedia, the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.