The inner parts of the Oslofjord contains some of the most exciting traces of Stone Age people in Europe

Archaeologists are now seeing how a landscape of fjords, straits and islands attracted people in the Stone Age. Few other places in Europe lend themselves as well to studying the lives and disappearances of the Stone Age people.

If you take the E6 motorway at Vinterbro, outside of Norway's capital Oslo, and head out towards the Nesoddtangen promontory, you will shortly afterwards pass the now quite unremarkable Havsjødalen.

Here, Stone Age settlements appear close together.

Until around 7 000 years ago, Havsjødalen was a fjord between the Drøbak Sound and Bunnefjord, a strait teeming with marine life – and people.

Few places in Norway offer as many traces of human activity in the Stone Age as here.

“We’ve understood for decades that this was an excavation area with enormous potential,” says archaeologist Axel Mjærum.

An improvement of the road to Nesodden municipality a few years ago opened up the possibility for the archaeologists to start digging in earnest.

A very special landscape

“Perhaps the densest population of people in Eastern Norway in the older and middle part of the Stone Age was found in the area around the inner part of the Bunnefjord,” says Mjærum.

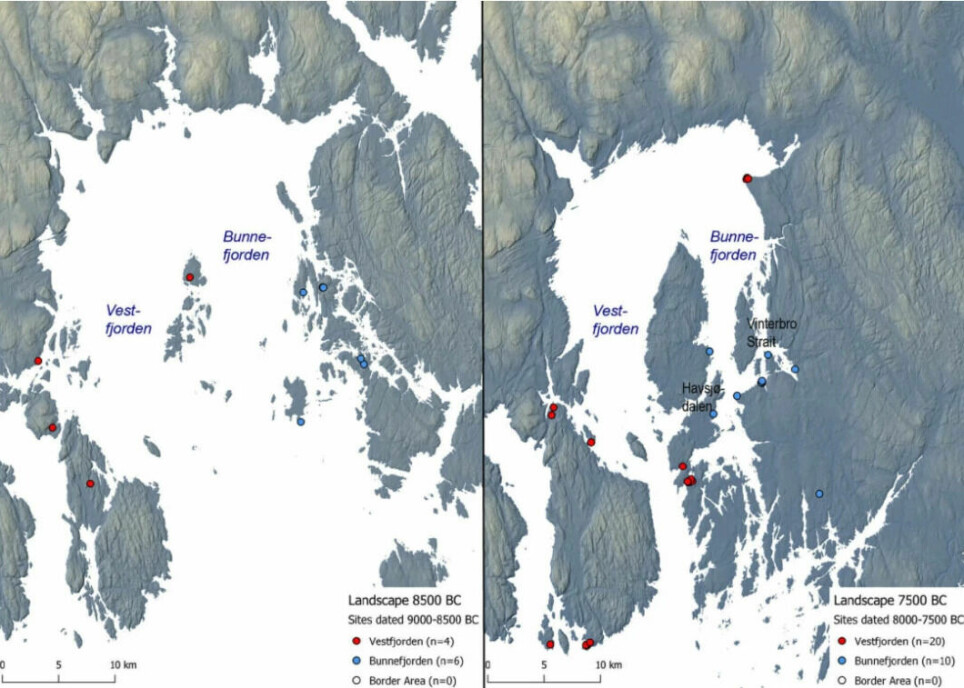

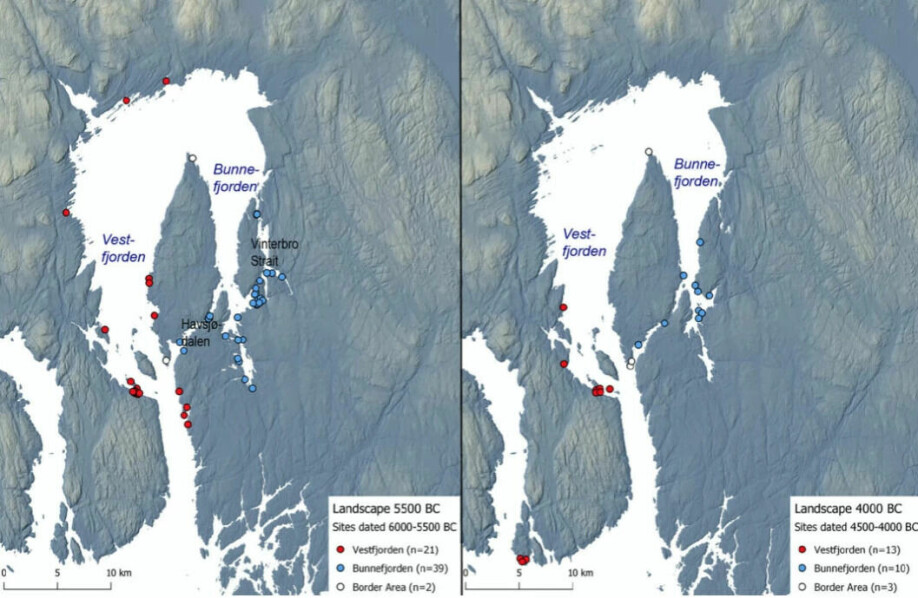

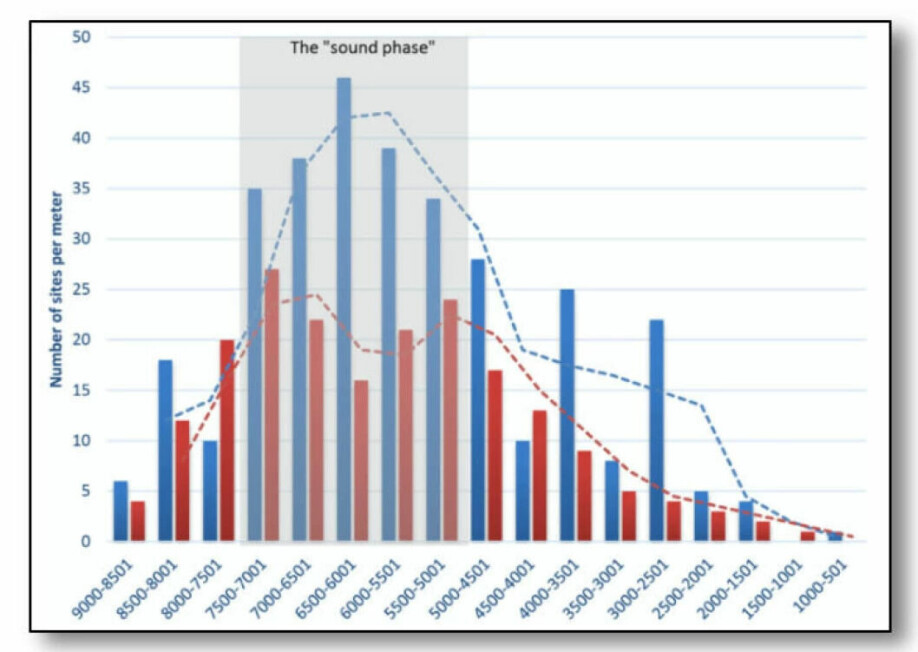

The archaeologist at the Norwegian Museum of Cultural History in Oslo led the excavation in Havsjødalen. In a separate study, he has now looked at how the rapid landscape changes after the ice age affected people and where they chose to settle.

“The Oslofjord is one of the populated places in the world where the shorelines moved the most during the Stone Age. It’s also one of the places where we find the most traces of settlements from this time,” Mjærum says.

These findings opened up some very special opportunities for Mjærum and his colleagues to study the connection between landscape change and people's settlements during the Stone Age.

Lived near the water's edge

In Stone Age Norway, people almost always lived near the water's edge, as they did in many other places in Europe.

People at that time commonly travelled a lot by boat.

They used the marine resources perhaps just as much as they hunted and gathered.

Archaeologists used to talk about people in the Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) as ‘hunter–gatherers’. Today they are often called ‘hunter–fisher–gatherers’.

Strait with lots of life

Try to imagine the shallow strait that stretched from Hallangspollen, just north of Drøbak in the Oslofjord, and into the Bunnefjord.

Here the ocean tide flowed in quickly and out again just as quickly.

The tide brought masses of nutrients along with it, perhaps almost like the Saltstraumen strait in Nordland county today.

It was teeming with fish. Lots of seals might have fed on the fish. Plenty of shells were found on the shore there.

Unique Stone Age landscape

During the Ice Age, an enormous glacier had weighed down the entire Nordic region.

Since then, the landscape around the Oslofjord has risen at least 200 metres above sea level.

“In the first period after the ice disappeared, the landscape rose by as much as ten metres every hundred years.”

“Today we find the very oldest settlements from the Stone Age around the Oslofjord almost 200 metres above sea level.”

“The youngest Stone Age settlements are today around 20 metres above sea level,” says Mjærum.

Opposite of Europe

In most of Europe, the opposite has happened.

Because all the meltwater from the Ice Age caused the sea level to rise a lot, many of the Stone Age settlements in Europe have disappeared under water.

Along the Norwegian coast, the sea level rose just as much, but the land rose even more throughout the Stone Age.

“The strong rebount in the inner Oslofjord is a completely unique setting for studying the Stone Age,” says Mjærum.

“Here we have fantastically rich material with Stone Age settlements, which are lacking in the vast majority of other places in Europe.”

People followed after sea level dropped

What did people do when the land rebounded and water levels retreated?

“Most often people moved to get closer to the shore again,” says Mjærum.

“Only as an exception do we see that people chose to stay where they were.”

The excavation at Havsjødalen reveals that there was extreme activity among the people here, especially in the last few years before the strait closed and the fjord disappeared.

Mjærum points out that the food resources in the ocean gave Stone Age people in the Oslofjord a stable food supply. The archaeologist believes Havsjødalen must have been a very resource-rich place.

Seascape vanished

How did things go when the seascape – with its fjords, straits and islands on the east side of the Inner Oslofjord – almost completely vanished towards the Neolithic (New Stone Age)?

“At first people stayed. We can see that it took a few hundred years before the Stone Age people here understood that their livelihood was about to disappear.”

Mjærum points to several possible explanations.

“One possibility is that people in the Stone Age might not have lived at the subsistence level that we imagine. But archaeologists are still having lively debates about how well people actually lived in the Stone Age.”

Humans disappear in the Neolithic

As the Oslofjord enters the Neolithic Age, we find less and less human activity in the region.

“We find distinctly fewer settlements down to 40 metres above today's sea level.”

“At some point when the landscape had changed sufficiently, this society that had previously flourished subsequently suffered a population collapse,” says Mjærum.

“Can this tell us something about what could happen with more global warming, sea level rise and coastal landscapes that might disappear in our time?” asks the researcher.

References:

Axel Mjærum: A Matter of Scale: Responses to Landscape Changes in the Oslofjord, Norway, in the Mesolithic. Open Archaeology, 2022.

Report from archaeological excavation: Havsjødalen, et boplassområde fra Nøstvetfasen (Havsjødalen, a settlement area from the Nøstvedt phase). Museum of Cultural History, UiO, 2021. (in Norwegian)

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------