Do we see the same colours?

ASK A RESEARCHER: We might agree that something is red or blue. But what if what I see as purple actually looks yellow to you?

We learn early on to call things blue, red, or yellow and might assume that means we also see the same thing.

But what if you and I don't see the same shade of red – even though we both call it red?

According to researchers, there are actually good reasons to believe that we don't perceive colours exactly the same.

“Even people with normal colour vision can experience colours differently,” Elise Dees Krekling writes in an email to sciencenorway.no.

She works as an associate professor at the University of South-Eastern Norway's National Centre for Optics, Vision and Eye Health.

What are colours?

“Light consists of invisible waves called electromagnetic waves. They have different lengths, and it's these waves our brain interprets as colours,” says Krekling.

Red light has longer wavelengths, while blue light has shorter ones. When light hits an object, some of the waves are reflected to our eyes.

“The combination of light waves that are reflected from a sweater, for example, is what causes us to perceive the colour as red or blue,” she says.

Special cells in the brain

When light waves hit the eye, they are captured by special cells in the retina called cone cells. Krekling writes that these cells are what allow us to see details and colours.

“How many types of cone cells we have, and how they register the light, affect how we perceive colours,” she says.

The eye's lens and a colour pigment in the retina also filter out some of the short-wavelength light. Therefore, the light that actually reaches the cone cells can vary from person to person, according to Krekling.

How we perceive colours can therefore be influenced both by how our eye is structured and by how the brain interprets the signals from the visual cells.

Krekling suggests that the type of light our eyes are used to, and how the light and colours around us affect each other, also play a role.

“It’s difficult to know for sure whether people see colours in the same way because colour perception is subjective. We might describe colours the same way and agree on the names, but the experience itself can vary. That’s why it’s hard to know if the shade of red I see is the same one you see,” she writes.

What does the research say?

Several studies have tried to find out whether people perceive colours in the same way.

In a study published in the journal Vision Research in 2017, participants were shown 36 different hues and asked to describe how the colours looked by placing them along two colour axes: red–green and blue–yellow.

They were also asked to choose one of eight predefined colour names that fit best, such as red, blue, yellow, or orange.

The results showed that people often described the same colours in different ways.

Another study from 2023, published in the Annual Review of Psychology, looked at how the ability to see and understand colours develops from infancy to adulthood.

The researchers found that even very young children already have basic colour vision after 2–3 months, but that the ability to distinguish and interpret colours continues to develop throughout childhood and adolescence.

The study also pointed out that experience and environment can play an important role. For example, children who grow up in special lighting conditions, such as north of the Arctic Circle, may develop a better sense fo certain shades of colour.

Can people with blue eyes see colours differently?

A commonly held belief is that people with different eye colours might see colours slightly differently.

According to Lene Aarvelta Hagen, this is not the case – at least not directly. Hagen is also a researcher at the National Centre for Optics, Vision and Eye Health.

“There might be indirect connections, since iris colour can be linked to other factors in the eye, such as light sensitivity or the filtering of certain wavelengths,” she says.

However, she points out that there are colours humans simply are not able to see, regardless of eye colour. Our colour vision is limited to the visible light spectrum.

Certain wavelengths, such as infrared and ultraviolet light, are beyond what we can perceive.

“Animals like bees and birds can see ultraviolet light. Artificial intelligence combined with special cameras can also detect these invisible colours,” she says.

When the world truly looks different

Some people actually do see colours completely differently than most – namely those with colour vision deficiency.

"This is often referred to as colour blindness, but it's rare for someone to completely lack colour vision,” says Hagen.

Most people have what is called red-green colour vision deficiency and see fewer shades within this spectrum.

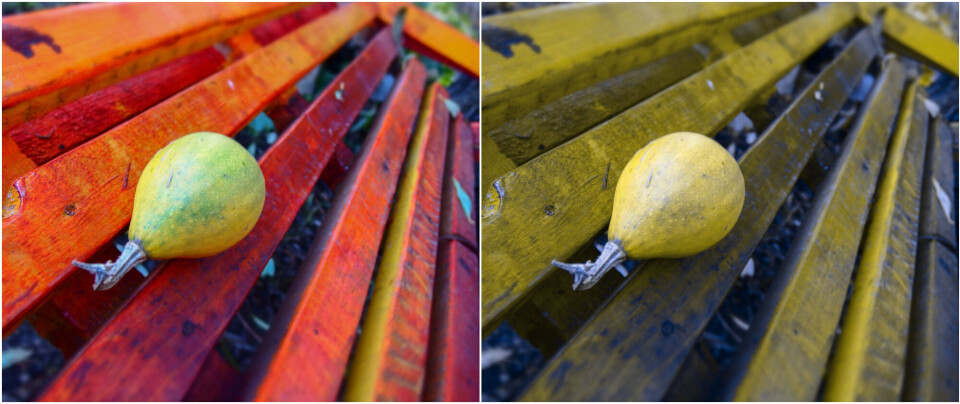

“Many with red-green colour vision deficiency confuse colours like purple and pink with grey, and yellow with greenish colours. In the most severe cases, red, orange, yellow, and green can all appear as the same colour,” she syas.

Colour vision deficiency is usually caused by genetic mutations that affect the function of cone cells.

“There are different types and degrees of colour vision deficiency. Some have a strong degree and only see a few colours. Others have a milder form and don’t notice it much in daily life,” says Hagen.

Colour vision deficiency can also develop later in life due to diseases that affect the eye or nervous system, medication use, or ageing.

“People with colour vision deficiency may face challenges in everyday life, but they usually have normal detailed vision,” she says.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.