Genetic tests uncover lethal legacy — at a price

It’s become ever easier to test for mutations that increase a woman’s risk of breast and ovarian cancer. But what kind of psychological burden does the test impose on women who take it?

Ann Kristin Kolstø-Johansen knew there might be a ticking time bomb in her genes.

Her mother’s mother died of cancer, and her mother and aunt both got breast cancer in their 40s and later died from it.

When her mother died from cancer at age 54, just after Kolstø-Johansen had given birth to her own daughter, she decided to get a test to see if she was genetically predisposed to the disease.

“I couldn’t continue with the uncertainty and risk that my own daughter would lose her mother at a young age,” the Stavanger, Norway resident said.

When the results showed she did indeed have a mutation that would make her more susceptible to breast and ovarian cancer, she was sad but relieved.

“I always felt like I must have the mutation,” she said. “When it was finally confirmed, it was a relief in a way to have a concrete answer, even though I was also crushed by the answer.”

Stress, but no regrets

Merete Bjørnslett, a researcher at the Norwegian Radium Hospital in Oslo, is interested in how women like Kolstø-Johansen handle the stress of genetic testing. She studied more than 300 women with ovarian cancer who had undergone genetic testing to see how they experienced the psychological burden of the test.

The women in the survey had been tested for mutations in the genes known as BRCA1 and BRCA2. Mutations in these genes increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer.

Late last year, Bjørnslett defended her PhD at the University of Oslo Faculty of Medicine on “Inherent Risk of Ovarian Cancer. Molecular Genetic and Questionnaire Studies in Women With Ovarian Cancer.”

“We found very high stress levels in women who got a positive test result, but also in roughly 10 per cent of women who received a negative test result,” Bjørnslett said.

In spite of the stress, none of the women in the study who Bjørnslett interviewed in depth regretted having taken the test, she said.

Uncovering familial risks

Less than half of the women in Bjørnslett’s study thought that their cancer could have been hereditary.

And because all the women in the study had already been diagnosed with ovarian cancer, their decision to get genetic testing didn’t matter in terms of determining their own cancer risk—although if found to have the mutation, their risk of breast cancer was increased.

Instead, all the women said the fact that family members could be monitored and have genetic testing was a very important reason that they themselves decided to get tested.

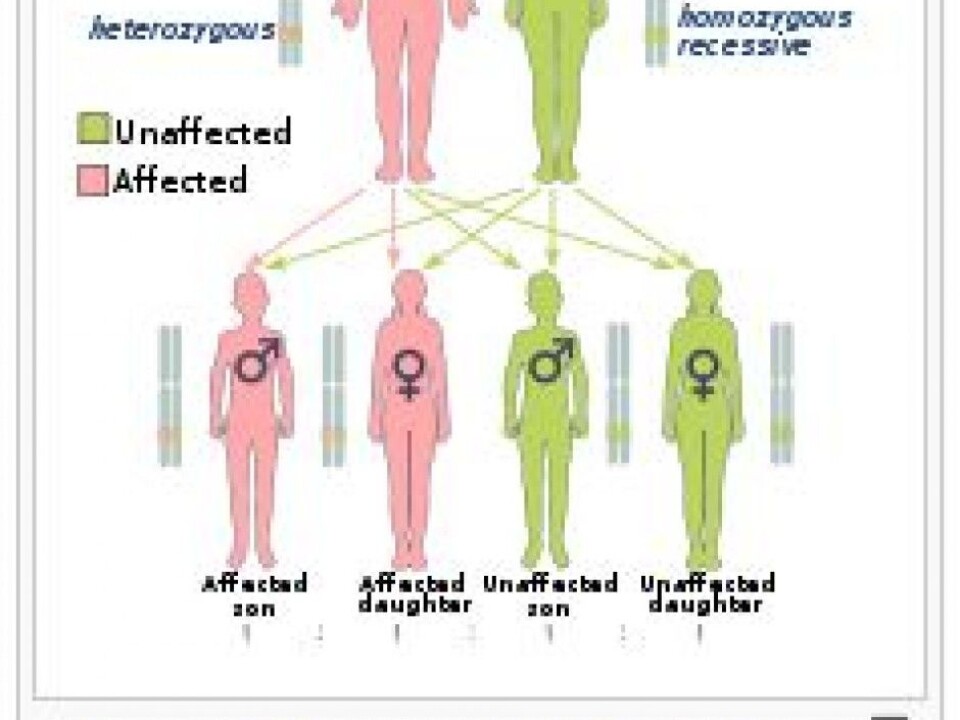

If a woman is found to have the genetic mutation, her immediate family and more distant relatives face potentially life-altering consequences.

A child whose mother carries one of the mutations has a 50 per cent chance of inheriting the mutation. It also means that the mutation had to have been inherited from one of the mother’s parents.

That also means that her siblings and members of her extended family would be at risk of having a hereditary predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer.

With knowledge comes an obligation

Half of all individuals with one of these gene mutations get breast cancer. That puts pressure on women for whom the test confirms that they carry the genetic mutation.

“They’re worried about their daughters and other family members. Women with these genetic mutations feel that they have a responsibility to inform all other family members, not just their closest family. This can be a great burden for women,” says Bjørnslett.

When a mutation is detected in a family, this does not automatically mean that other family members also have the genetic defect, although they have an increased risk of being a carrier, she said.

“By identifying a mutation, genetic testing can clarify which relatives might be predisposed to cancer, and doctors can follow up on these individuals clinically, and thus prevent them from becoming ill,” Bjørnslett said.

But it also means that relatives are involuntarily faced with the question of whether they will undergo genetic testing.

First no, then yes and an operation

When Kolstø-Johansen was a teenager, her mother was offered genetic testing at Haukeland Hospital.

“At the time, neither my mother nor I wanted to know if we had a hereditary predisposition, because we did not know what kinds of preventive measures were available at that time,” she says.

Now, after she decided to have the test and found that she had the faulty gene, Kolstø-Johansen decided to have both her breasts removed prophylactically.

“It wasn’t easy, because it’s sad to have to remove a healthy part of your body,” she said. “But I didn’t really feel like I had a choice.”

She said she simply could not take the chance of living with an increased risk of getting cancer.

“It wasn’t just to save my life, but also because of my daughter. I don’t want her to lose me as early as I lost my own mother,” Kolstø-Johansen said.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no