Genetic test queues generated by Angelina Jolie

Since Angelina Jolie made her double mastectomy public in 2013, Norwegian women have streamed to hospitals to test against hereditary breast cancer.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

All the major hospitals in Norway that conduct genetic testing marked a spike in queries from women in the months after the news about Jolie splashed headlines. Referrals for tests rose by 70 percent at Oslo University Hospital.

Now, nearly a year later, the number of referrals is still 50 percent higher than before the superstar’s breast removal.

“This is brilliant,” says Lovise Mæhle, chief physician at the Norwegian Radium Hospital’s Department of Genetics.

“Angelina Jolie has done many women a great service by drawing attention to hereditary risks of breast cancer and ovarian cancer. Even if the women didn’t personally become more conscious of it, their MDs were prompted to refer patients to genetic testing.”

New York Times

In May 2013 the famous actress wrote a letter to the editor of The New York Times. She related her decision to have both breasts removed.

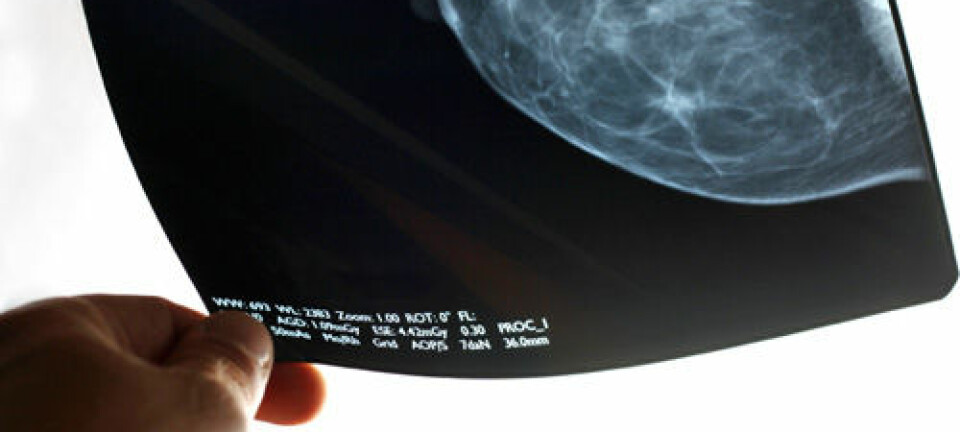

Jolie had taken a genetic test which revealed she had a hereditary breast cancer gene, a mutation in a gene called BRCA-1 [abbreviation for breast cancer -1]. This gave her a very high risk of developing breast cancer and ovarian cancer.

Many in the dark

About 5,000 men and women in Norway have already been found to have the same mutation as Jolie. Scientists think about that many again are unaware of having the mutated gene, which can shorten the life of women on average by 20 years.

Very few who have the BRCA-1 mutation contract cancer while in their 30s. But the risk of breast cancer mounts with time.

From the age of 35-40 the risks of ovarian cancer rise too.

By age 60, about 70 percent with the defect will develop breast and/or ovarian cancer unless preventive action is taken.

Everyone should be able to test themselves

Angelina Jolie had reason to be on the alert. Her mother died in 2007 after battling cancer for a decade.

In Norway the only women offered a genetic test are those who are already diagnosed with cancer, or who have a high incidence of breast and ovarian cancer in their family.

Not all women with this mutation have had a family history of such cancers. Many families are small, and the mutation can have passed through several generations of males. So these women are not spotted by the health services until a prospective cancer is diagnosed.

Mæhle hopes that soon everyone who wants the test will get it. The Norwegian health authorities have been restrictive, in part because of a notion that women with cancer should be protected from learning it could run in their family.

“We know that a high proportion of the women who are offered the genetic test agree to take it, even though it can make them confront the difficult decision about undergoing preventive surgery.

These patients have to make that decision themselves. They don’t need the authorities to make it for them,” asserts Mæhle.

“Most of them are glad to get the opportunity to make a choice which could enable them to be around longer for their children – a choice that women in previous generations never had the chance to take.”

Mammograms not enough

A timely mammogram does not improve survivability much for this group of breast cancer patients. The safest thing to do is to remove both breasts and the ovaries before the cancer can develop and spread.

According to US media the actress Jolie now has to mentally prepare for the latter operation as well.

“It has a big impact when celebrities like her are open about the disease. Other women can see that even she, whose career partly depends on her body and appearance, can make this rough decision. I think it encourage many other women,” says Mæhle.

Genetic counselling fills the waiting lists

In Norway everyone who is cancer-free has to get genetic counselling prior to being given a genetic test. This ensures that the persons being tested have been give thorough information about the possible consequences if the mutation is detected. They need to know what they are facing.

But it also creates long queues for genetic tests at Norwegian hospitals.

Currently at Oslo University Hospital the wait for genetic counselling and testing is up to 14 months, even though the test is fairly easily done in a laboratory.

Lovise Mæhle deems genetic counselling important, but she thinks it should be simplified so capacity can be increased and waiting lists foreshortened.

In her view, documentation shows that those who test positive – in other words have the BRCA-1 mutation – tackle the information well.

Knowledge can be a problem

Åshild Lunde has recently presented her doctoral dissertation about genetic counselling at the University of Bergen.

“Even though this new genetic knowledge will lead to better prevention and treatment of disease, the awareness can be problematic, both for the individual and for society,” she says.

The consequences of genetic findings are uncertain. A strong focus on genetic dispositions is bound to alter people’s lives. At the same time, when in touch with the health care system, patients are used to receiving specific advice about what they should do to improve their health.

“It’s a challenge providing information and counselling when the consequences of genetic testing are uncertain. Due to this complexity, counselling can sometimes be more confusing than illuminating,” says Lunde.

Ethical problem

Genetic counselling is steeped in ethical rules about not pressing patients to take a given course of action. The counselling should be a catalyst to help patients choose freely themselves.

But Lunde found in her PhD work that the health personnel who give genetic counselling sometimes find it ethically perplexing to refrain from giving patients concrete advice.

“We need to know more about how knowledge of genetic issues impact people’s lives so we can give counsel while protecting the interests of patients and their families,” she asserts.

------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling