Seven rare gold pendants were sacrificed 1500 years ago in Østfold county of Norway

It must have been a considerable ritual act, reserved for only the most privileged in society, according to researchers.

The seven gold pendants – known by the name of bracteates – were found in a field and near a small hill at the edge of the field.

If this spot was in fact a place where gold bracteates would have been laid down for sacrifice, it has been disturbed in modern times by farming.

Save for an assembly of gold artefacts which included one bracteate which was found in Møre og Romsdal in 2014, it has been 70 years since similar findings were done in Norway.

“Such votive hoards are incredibly rare”, three archaeologists write in a blogpost on forskning.no (link in Norwegian).

Jessica Leigh McGraw, Margrete Figenschou Simonsen and Magne Samdal are all archaeologists working at the UiO Museum of Cultural History , and they have just undertaken an excavation on the site.

A scandie take on Roman culture

A total of about 160 bracteates have been found in Norway, whereas in total around 900 such pendants are known. They are considered a Scandinavian phenomenon, and when found in Germany and England are presumed to have been imported to those places.

The inspiration for the pendants, however, are the Roman Empire Medallions.

“In homely tradition, the portrait of the emperor has been replaced by Norse gods and animal figures in Germanic style”, the archaeologists write.

“People in Scandinavia took ownership in a status item from the Roman culture, gave it a Norse look and made it their own.”

Animals, humans, symbols and runes

The name bracteate is derived from the Latin bractea – meaning a thin piece of metal.

The pendants were single-sided, made out of gold, and usually worn as jewelry. They could also be laid down as votive gifts to the Gods, as hoards of gold bracteates suggest.

Bracteates are classified according to what they depict. The seven that were recently found in Råde in Østfold, are of the types C and D.

Type C bracteates depict scenes of a person on the back of a horse-like animal, often in combination with birds, other symbols and runes. The dominating feature, however, is a large human head with prominent hair.

Type D bracteates are different stylistically from the other classifications, and are assumed to be the youngest variants, dating from the 6th century AD. They depict various highly stylized animals and can be quite hard to understand and interpret today.

Pleasing the Gods

The bracteates are from the so-called Migration Period, a time of widespread migrations in Europe that mainly took place between the 4th and 6th century AD.

Norway has rich findings from this period from sites like farms, graves, hillforts and stray finds. Imported items from the Roman Empire as well as copies of antique status symbols show that Norway had cultural and economic ties to the continent, the archaeologists write in their blogpost.

This is also evident in the gold bracteates.

“There is little doubt that these were items connected to aristocratic communities within a Germanic elite in Scandinavia”, they write.

In the years AD 536-540 however, a series of volcanic eruptions lead to thick clouds of ashes that affected the climate. This is referred to as the Fimbul winter in Norse literature. The sun did not shine for more than a year, crops failed, and people starved.

“We don’t know if the gold bracteates from Råde were laid down before or after 536”, the archaeologists write.

“But it appears as though gold offerings become larger and more numerous during the 500s. In a time of bad years and insecurities, people may have felt a heightened need to try and avoid dangers and seek protection. The Gods needed pleasing, and an increased amount of gold offerings may have taken place”.

Read more about the Fimbul winter in this article: The long, harsh Fimbul winter is not a myth

Will be studied in detail

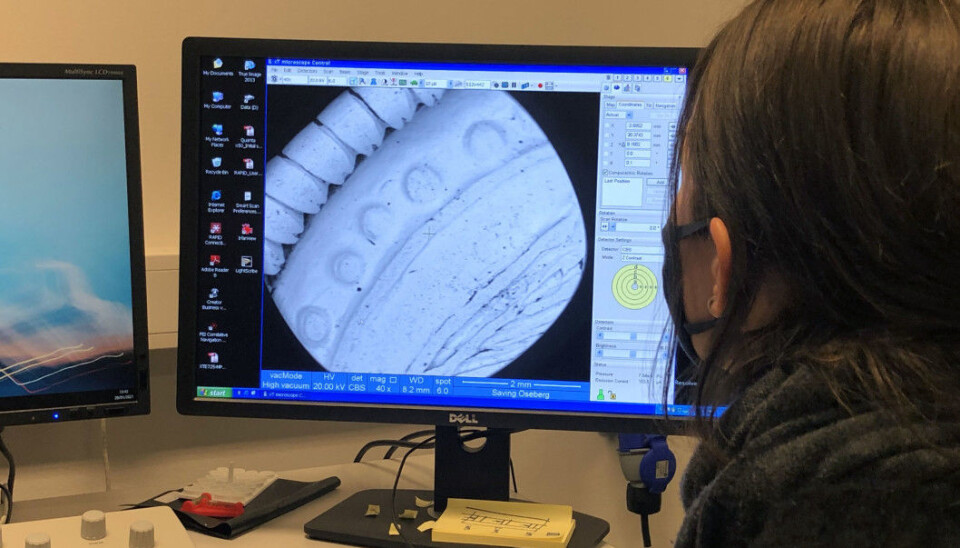

The seven gold bracteates will now be studied in detail at the UiO Museum of Cultural History in Oslo.

Some of them are a bit bent and the motifs are partly hidden.

Using advanced technology, the archaeologists hope to be able to say something about how the pendants were made, and perhaps even by whom and where.

They will also compare the newly found bracteates to old findings. This might tell us something about connections between the elites in Scandinavia or Northern Europe.

“Laying down seven gold bracteates must have been a considerable ritual act, reserved for only the most privileged in society”, the archaeologists write.

“Thus, they are also bearers of stories from the time before they were given as offerings”.