The gjellestad-dig:

Layers of soil and turf tell the tale of a grand Viking ship burial

The Gjellestad Viking ship has more or less disintegrated. But the ongoing dig to salvage the remains, the first Viking ship dig in Norway in a century, is still finding important clues to what happened here, a long time ago.

Once upon a time, or more precisely, sometime between the late 700s and the early 900s, the people who lived in what today is South-Eastern Norway, buried a king, or a queen. Or a king and a queen. Somebody powerful.

“It must have been somebody who had an exceptional role in society”, Camilla Cecilie Wenn says on the phone from the excavation site of the Gjellestad Viking ship.

Archaeologist Wenn is the leader of the excavation.

“We have many smaller boat graves in Norway. If we compare this to them, then clearly we are talking about a king or a chieftan, somebody who had a lot of power in this area, locally and maybe also regionally. It was clearly an elite burial”, she says to Sciencenorway.no.

“For one thing, you’d have to have a spare ship that could be used simply for burying somebody. That pretty much places you at the top”.

While we’re talking, somebody passes Wenn with a plastic bag, but apparently it doesn’t contain anything of interest. Her job for the day is to register finds in an excel sheet. Around 12 people are sitting or lying around the ship picking through the soil as carefully as possible. Students from the University of Oslo have arrived to help the team finish on time.

So far today, Wenn has registered a few pieces of ceramics, bone and fragments of iron.

Carefully rushing to get it all done

“This is very different to what we’re used to”, Wenn says.

“Everything is so fragmented and broken down that we have to work extremely carefully, so we understand what we find as we go along, and so that we can understand what we have removed”.

Winter is coming to Norway and working in the tent set up to protect the excavation site has become more difficult. It’s cold. The work slows down. Water hoses need to be kept from freezing so they can do the job of helping sift through the soil. At the same time, the cold helps preserve the remains of the ship. Five more days are left until the dig is supposed to be officially over.

Unless they find something unusual. Or perhaps the wood further down is more well preserved, in which case it needs to be dug out properly.

“It’s about to become really exciting here at Gjellestad”, says Wenn.

“We’re getting closer to the bottom of the ship, and thus closer to perhaps discovering items that may have been laid down here, as well as the rest of the construction of the ship”.

The hope is to find something that can tell us more about who was buried here. Perhaps some fragments of clothes. Or teeth, that would be hitting the jackpot. Teeth could contain DNA which allows for determining everything from age to gender, while isotope analysis could tell us what the person used to eat and what kind of environment they grew up in.

“There’s probably a higher chance that we find fragments of human teeth than bones”, Wenn comments.

“The potential here is huge”

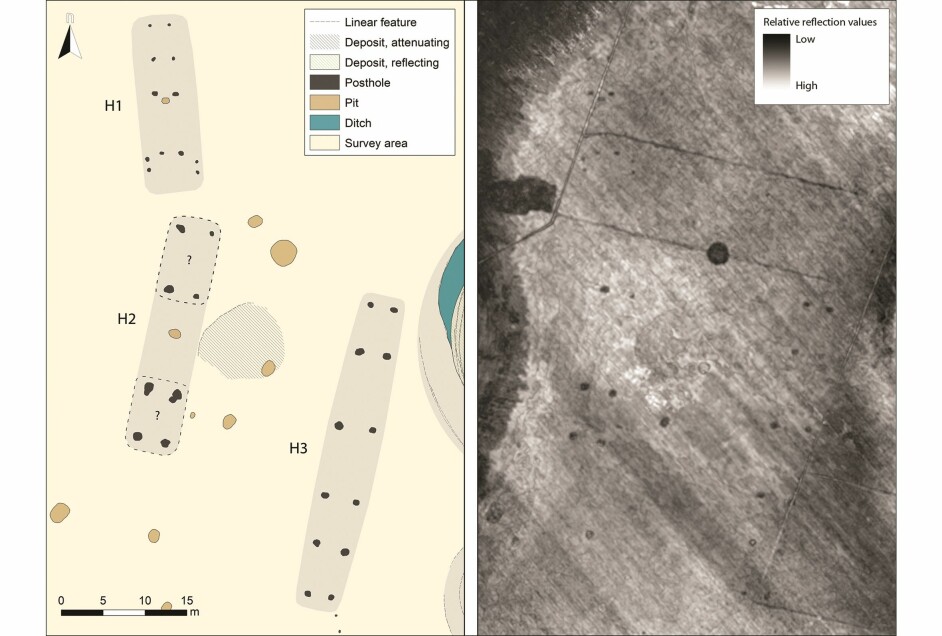

Discovered only a couple of years ago with a so-called georadar – an instrument mounted on an ATV or a small tractor that uses radar pulses to map patterns and artifacts found under the ground – it became clear that the Gjellestad ship was in dire conditions. It was a question of digging now, or forever losing the information still present in the mound.

Much has been made of the fact that it has been a century since a Viking ship from a grave mound was last excavated in Norway. And although it has been very clear from the get-go that an actual ship would not materialize from this grave, some commenters have expressed disappointment at the lack of glorious findings.

But these days, with new technology, a sample of soil may be as interesting as a well-preserved artifact.

“We’re going to get major findings from this dig”, Wenn assures.

“Our work lies more in interpreting differences in layers of soil than finding spectacular things. Finding spectacular items can be fun, but these are not always the things that tell us the most about the past”, she says.

Wenn believes the Gjellestad dig may give us a completely new and different kind of knowledge compared to that achieved through the excavations from a century ago.

“The potential here is huge. We are working with completely different methods in collaboration with the natural sciences, so our results may be completely different to what they found way back then”, she says.

The stage of a grand ceremony

The ship itself collapsed a long time ago, having both been looted perhaps a few generations after the burial, while the mound was still intact, as well as plowed down to create better conditions for agriculture in the late 1800s.

“There are tales of boat parts being found in this field when they removed the mounds. We don’t know if these stories are true, but if so, then the ship was probably fairly well preserved at the end of the 1800s”, Wenn says.

The end of the 1800s is also the time when the other famous Norwegian Viking ships were excavated, like the Gokstad ship, excavated in 1880 and the Oseberg ship, excavated in 1904. But it would appear that the farmers at Gjellestad were more interested in ploughing the earth than examining Viking remains.

Parts of the burial mound have collapsed with the ship, and thus been preserved. And this is exciting. By studying the remains of these collapsed layers of soil and turf, the archaeologists have discovered how the burial mound was built.

“You don’t just dig a hole, put a ship in it, and then you’re done with that”, Wenn says.

“What we find is that there was a really broad ditch around the ship, which has probably been open for quite a while, before the ship was covered. It might have been filled with water, creating a water mirror”, says Wenn.

The archaeologists imagine that this ditch created a separation between those who were part of the burial ritual in the ship, and those who were merely watching on the other side.

“It was a like a stage, where a show or a ceremony was performed”, Wenn believes.

And it went on for some time, the analyses of turf show.

“Did they come here every day, or with a few weeks in between to perform rituals? This we don’t know. But that it was a process that took time and was composed of different stages seems clear”, she says.

Analysing the material, finding the patterns

Wenn has excavated a site or two before in her career. The likelihood of heading the dig of a Viking ship may not have seemed very high, yet here she is.

“This is very unique. For many of us, who specialize in this period, this is one of the biggest things imaginable to be part of”, she says.

And the work of course, is not over once the dig ends. When the tent is taken down, samples need to be sent to various labs for a variety of analyses. Findings need to be systematized and catalogued, 3D models made. And then of course analysis. What are the patterns, what did they find, what is the story?

Then there’s the area surrounding the burial mound. Using georadar, settlements have been found, the remains of what may have been a feasting hall or a house for rituals, numerous other burial mounds, and a bit further on southwest, a possible trading site by the sea-shore. The past few years have seen a number of metal detector finds in the area as well.

Where previously it was thought that power during this time was centered west of the Oslo fjord, the Gjellestad-area on the South-Eastern side of the fjord is appearing to have been a powerhouse of sorts.

“It’s really exciting to do a dig, one house, one ship. But it’s when you see it all in a bigger context that society starts to appear”, says Wenn.

“When you see the Gjellestad Viking ship in a wider frame, you can start appreciating the site as an important place of power for the Viken region, and not least on a national scale. Only a handful of places in Norway are comparable.”

———

The biggest findings so far

The Gjellestad-archaeologists haven’t just found soil. Here’s a list of the biggest findings so far:

1. Three fragments of at least two different glass beads

2. A nail with an anchor-shaped rove

“It was really big, and it took time and extra competencies to understand what it was. It’s a big nail that was used to fasten the floortimber (the lowermost part of the frame) to the planks in the inner hull construction of the ship. One of the things we really want to be able to is to find out how the ship was constructed. When we found this anchor-shaped rove, we could calculate where the frames of the ship were, using knowledge from other known Viking ships. With this as our guide, we were now able to identify 8-10 of these frames in the soil. Given that the wood here is mostly decomposed, so what we’re looking for is nuances in soil, it was a lot easier to find when we knew where to look”, Wenn explains.

“All Viking ships are unique, and all details of construction give us a new understanding of the techniques used to build them.”

3. Fragments of a comb

4. Animal bones

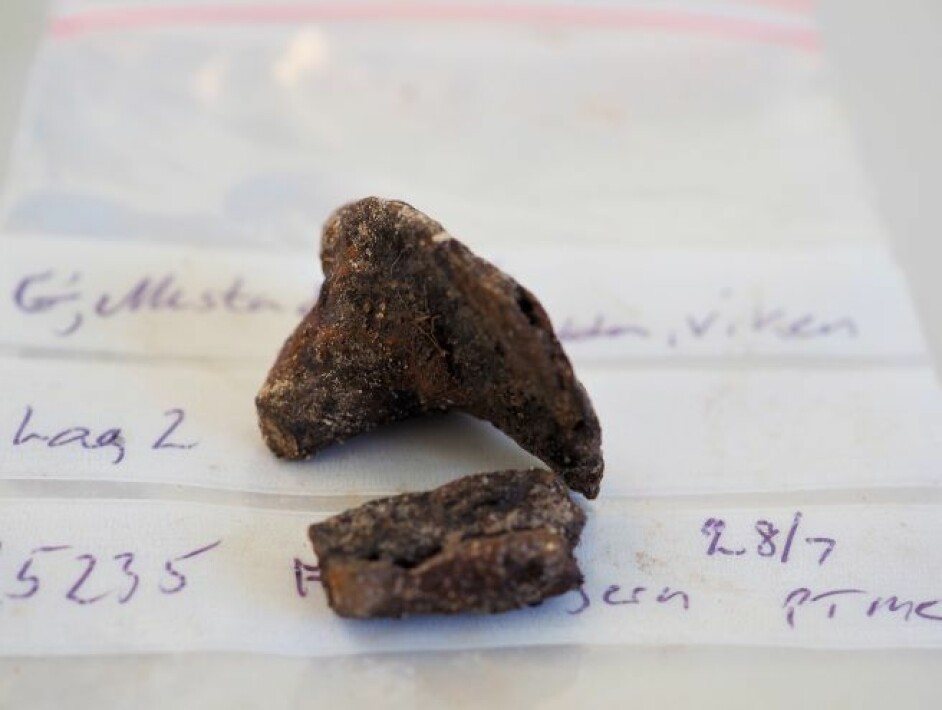

The archaeologists believe the bones are from large animals, perhaps a horse or cattle. They have also found fragments of teeth from animals that will be analysed.

The animal bones pictured here (the orange shapes) were uncovered in the mid/northern section of the ship.

5. Ship nails

The ship nail pictured here, which is almost completely intact, was discovered in situ, meaning in its original place.

6. Fragments of copper alloy

“These fragments could have been ornamentation on objects made by wood or bone. It suggests that these were rather nicer objects”.

———