The long, harsh Fimbul winter is not a myth

Half of Norway and Sweden’s population may have died. Researchers now know more and more about the catastrophic year of 536.

"First came the Fimbul winter that lasted three years. This was a warning of the coming of Ragnarok, when everything living on Earth came to an end. "

This is how the story of the long harsh winter, called the Fimbul winter in Norwegian, begins, both in Norse mythology and in the Finnish national work of epic poetry, the Kalevala.

But why are stories that warn of a frozen end-time found in Nordic mythologies?

In recent years, researchers in Norway and Sweden have found increasingly clear evidence of a disaster that struck the planet 1500 years ago.

The disaster must have hit Norwegians and Swedes extremely hard — as hard as the Black Death. The same may have happened in the Baltics, Poland and northern Germany.

The moss scientist’s theory

In 1910, the Swedish geographer and reseacher of moss Rutger Sernander first launched the theory that the Fimbul winter may have been a real event in the Nordic countries. His hypothesis was that this was due to a climate disaster between 2000 and 2500 years ago.

For a few years, people listened to Sernander and his ideas. Then came the doubt, because archaeologists couldn’t find traces of such an ancient disaster.

We now know however, that a climate disaster struck the world — and especially the Nordic countries — just 1500 years ago.

And we know that it may have been followed by another disaster. Which might have been just as big.

NASA and a Swedish archaeologist

The new hunt for the Fimbul winter began with the US space agency NASA, in 1983.

At this time, two NASA scientists, Richard Stothers and Michael Rampino, published a scientific overview of known volcanic eruptions back in time. Much of their work was based on ice cores taken from ancient inland glacier ice on Greenland.

Archaeologists read the article. They understood that something very dramatic may have happened in the year 536.

Central to the new hunt for the Fimbul winter was Bo Gräslund, now a retired professor of archaeology at Uppsala University in Sweden.

Gräslund was first to suggest that the Fimbul winter was a real event, and that it took place in the years after 536. He also pointed out that the 13th century Icelandic historian Snorre in his book Edda was not only concerned that it was very cold and the winters were snowy — Snorre was also concerned because there were no summers for several years in a row.

Several years with no summer

The Fimbul winter then, meant several years in succession without a summer — which would have consequences about which we can only speculate for people who lived in the far north 1500 years ago.

Gräslund was also the first to estimate that the population of Sweden was halved in the 500s.

In the early years, many did not believe Gräslund's hypothesis.

In 2007 he publishes the article “Fimbulvintern, Ragnarök och klimatkrisen år 536–537 e. Kr.” (Fimbulvintern, Ragnarök and the climate crisis in the year 536–537 AD) in the Swedish journal Saga och sed.

After that, researchers began their hunt for the Fimbul winter in earnest.

Natural scientists and archaeologists make discoveries

In recent years, many discoveries have been made that clearly suggest that Bo Gräslund is right.

In Norway, pollen has been found deep in several bogs, evidence of a dramatic event that clearly changed the cultural landscape for a long time afterwards.

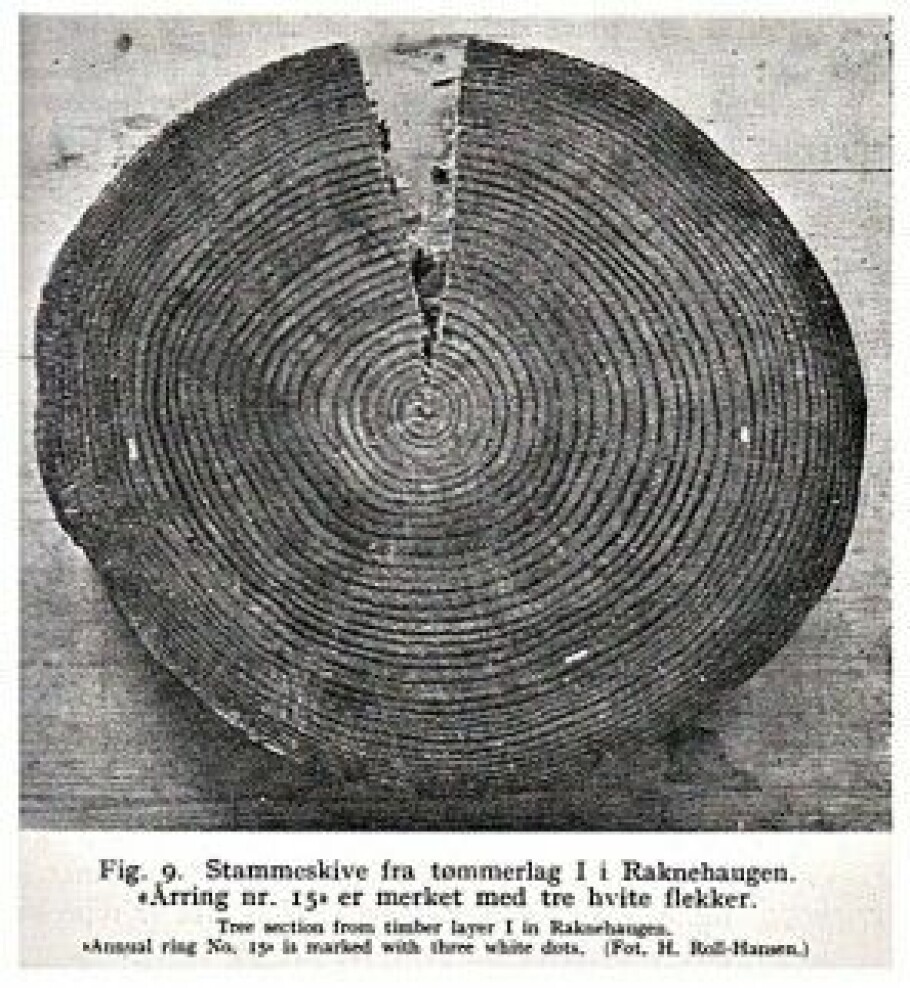

Tree rings from old trees provide another important clue.

Now that archaeologists know what to look for, these scientists are also finding more and more clues in their material. Today, archaeologists see that something dramatic happened to the farmsteads in Norway and Sweden 1500 years ago.

People moved. Or they disappeared. There are almost no grave finds from this period. Fine jewellery was no longer made. Beautiful pottery traditions in western Norway ceased.

Life seems miserable.

Also, more gold was sacrificed to the gods.

People left the mountains

Per Sjögren works as a paleoecologist at the Tromsø University Museum. He specializes in looking for clues about life from the past.

It was during his work on a major research project that examined changes in the Norwegian mountain cultural landscape that Sjögren and colleagues came on the trail of the Fimbul winter in Norway.

In pollen samples taken from boggy soil in the mountains, they saw clear traces of a dramatic climate event 1500 years ago.

“We found the first traces of the Fimbul winter in northern Norway. Eventually we found the same thing in southern Norway,” Sjögren says.

“We see that the landscape has grown back. That people and animals must have left the cultural landscapes they had used in the mountains,” he says.

Who left Storesætra in Stryn?

Kari Loe Hjelle is professor of natural history at the University of Bergen. She is interested in what pollen and other evidence from the past can tell us about people's lives — at a time when there are no written sources about life in Norway.

Hjelle describes a diagram that was created by paleoecologists when they examined the amounts of grass and tree pollen deep in the soil at Storesætra in Stryn. This was a sæter, or summer farm, just below Jostedalsbreen, in an area that people have used since the Stone Age.

The diagram clearly shows how people used this landscape between year 0 and year 500. The pollen record shows lots of grass and smaller trees.

Then something happens in the 500s. Grass pollen decreases dramatically. The trees were coming back.

Coal dust is another indication that people are using a landscape. This also disappears from Storesætra in Stryn in the 500s.

Massive devastation of farms in Norway

Frode Iversen is Professor of Archaeology at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo.

“From the 1960s, it has been known among archaeologists in Norway that there was a massive devastation of farms in Norway from the mid-500s. This is a known phenomenon, especially in Rogaland County,” he says.

But why were the farms ruined and abandoned?

It has been speculated that the Justinian plague that struck the world at that time also came all the way to Norway.

“There was a lot of attention to this among Norwegian archaeologists decades ago. Since then, we haven’t thought about it much, until it again became topical because of Bo Gräslund’s new theory on the Fimbul winter,” he says.

Now Iversen and colleagues have summarized much of what they know about the Fimbul winter in Norway in some of the chapters in their book "The Agrarian Life of the North 2000 BC – AD 1000". It is available (in English) free of charge as a PDF book at Cappelen Damm here.

“We see a very sharp decline in activity in Norway in the 500s,” Iversen says.

Nearly 90 per cent fewer discoveries

Morten Vetrhus wrote his master’s thesis at the University of Bergen on what happened during the transition from the Migration Period to Merovingian Period — in other words, before and after about 550.

He reports a sharp decline in the number of sites where archaeologists found something interesting. The decline in discovery sites was as much as 70 per cent.

Even greater was the decline in the number of archaeological finds in Rogaland from the Migration Period to the Merovingian Period. This decline was 87 per cent.

This despite the fact that the Merovingian Period lasted a hundred years longer than the Migration Period. Even in a fertile area like Jæren, parts of the landscape was completely emptied of people.

“This is a very strong decline. What happened to these people? Why do we stop finding evidence of them?” Iversen asks.

Smaller farms abandoned

Iversen believes a strategy people used to face the crisis was to abandon the small and least productive farms. Larger and more centrally located lands were instead divided into smaller production units.

A lack of labour made it difficult to maintain farm operations in Rogaland and likely in the rest of Norway at the levels it had been at before the disaster in the mid-500s.

Iversen also wonders if the mass death caused more land to be available for people who survived. This may explain why archaeologists find traces of agriculture in Norway in the latter part of the 500s that reflects more animal husbandry. This is something similar to what other historians believe happened after the Black Death around 1350.

There are also some examples of new power centres being established in Norway after the disaster.

Raknehaugen in Romerike — the largest burial mound in the Nordic countries — probably reflects this. There were fewer powerful people left in the country, but those who remained might have had greater control and were even more powerful than before the disaster. Archaeologists have found evidence of the same in Sweden.

Iversen has no doubt that the disaster must also have had a major impact on social structures in Scandinavia.

His theory is that the disaster hit the upper and lower layers of society the hardest.

As a consequence, after the disaster, a "middle class" grew larger. And with this, a society where people were more equal than before.

The art of goldsmithing disappears

Ingunn Røstad, also a researcher at the Museum of Cultural History, has shown that the clothes and jewellery used by the Iron Age people in the 600s and 700s were of simpler quality than from before the early 500s.

“Fine gold and silver jewellery were less common,” says Iversen.

“The jewellery that was made became simpler. It almost looks ‘homemade’.”

Climate or plague?

Iversen now wonders if it was the climate disaster alone that destroyed the population.

Or was it — as more and more scientists are tending to believe— a combination of climate and a serious epidemic?

The Justinian plague hit Southern Europe in the year 541.

There’s no evidence that it also reached all the way to the Nordic countries. But researchers who have opened graves have recently been able to establish that the plague came to Germany. That makes it not unlikely that it also hit Norway.

The bacterium from the 500s — Yersina pestis — is the same that hit Europe during the Black Death in the 1300s.

In the vast city of Constantinople, it is estimated that about 40 per cent of the inhabitants died during the Justinian plague in the years 541 and 542.

The Justinian plague in northern Norway?

One of the world's foremost research communities on plague is found today at the University of Oslo under the leadership of Professor Nils Christian Stenseth.

Researchers there have determined that the plague bacterium must have been imported into Europe time and again. They also see that climate has a lot to do with the development of plagues. As the climate became colder, the rats died. Then the fleas that carried the plague shifted to people.

"If we are going to find traces of plague on people from as far back as the 500s, my tip is that we investigate skeletons in northern Norway," Iversen said.

The climate is cooler in northern Norway and skeletons are better preserved. In addition, some bone remnants in northern Norway are found in calcareous shell sand.

Iversen warns that scientists will need a lot of luck to find plague bacteria in people who lived 1500 years ago.

The entire Norrland depopulated

To find more pieces of the puzzle surrounding the Fimbul winter, we now travel to Sweden.

In recent years, several researchers have taken an interest in what Swedish scientists now commonly call "the incident in 536".

Now that Swedish archaeologists know what to look for from this time period, they, like their Norwegian counterparts, they find evidence of the disaster.

Archaeologists see that a large number of Swedish farms were abandoned in the mid-500s. Large areas where animals had grazed are being repopulated by trees — just like in Norway.

The northern part of Sweden — Norrland — may have been completely depopulated.

Half of Swedish farms abandoned

Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist is both a historian and climate scientist at Stockholm University.

“It is now clear from Swedish archaeological research that perhaps as much as 50 per cent of the population disappeared from Mälardalen, Öland and Gotland. Almost half of all buildings were abandoned,” he says.

Climate scientists believe there must have been a huge volcanic eruption in the year 536.

“It probably happened somewhere in the non-tropical part of the northern hemisphere. The outbreak caused large quantities of aerosols (tiny particles) to be sent high into the atmosphere,” he said.

This was followed by an even bigger volcanic disaster in the year 540.

“This must have happened somewhere near the Equator. Maybe it was El Chichón volcano in southern Mexico,” he said.

The tiny particles from the two volcanic eruptions remained in the atmosphere for several years, leading to strong cooling in the northern hemisphere. Ljungqvist points out that there are now a number of studies of annual rings in old trees that confirm this.

He points out that the cumulative effect of two huge volcanic eruptions in the years 536 and 540 was what made this cooling quite exceptional and very long lasting.

“Today we know that this is probably the most severe cooling the Earth has experienced in more than 2000 years,” says Ljungqvist.

Frost in trees in the middle of summer

It was so cold that frost formed inside trees in the middle of summer.

Traces of this have been found in Russia, among other places. It is very rare for trees to freeze internally during the summer.

“The cooling may have been 3-4 degrees on average in the summer of 536 and somewhat less the years that followed. About the same time, the cooling resumed in the year 540. It may not sound like much. But the cold was hardly spread evenly throughout the summer. Certain periods in the summer were probably extra cold, while other parts of the summer probably had normal temperatures,” Ljungqvist says.

Another issue was the low sunlight. Sunlight was unable to penetrate the ash layer in the atmosphere. Without sunlight, plants failed. People were not able to grow food. They couldn’t grow hay for their animals.

Ljungqvist notes that the cold summers after 536 in some places seem to have experienced heavy rainfall.

Grain matured, but rotted.

Then came the plague

There are no written sources from the Nordic countries from as early as the 500s.

- But in Italy, historian Flavius Cassidorus in 536 reports a sky full of dark clouds and sunlight lasting just a few hours a day.

- In Constantinople, the historian Prokopios writes of a constant solar eclipse.

- From Ireland there are depictions of famine.

- From China there are written sources that speak of snow in the middle of summer.

Then — in the year 541 — the Justinian plague comes to Europe.

“In southern Europe we know this plague epidemic was as brutal as the Black Death 800 years later. There is a lot of evidence that the plague in the 500s also reached Northern Europe, although we do not have written sources that describe it,” says Ljungqvist.

In 2013, German scientists were able to confirm that three people buried in today's Germany were infected by the pest bacterium Yersina pestis during this period.

If the plague reached north of the Alps, Ljungqvist considers it likely that it also reached Scandinavia.

“Together, the dramatic cooling of the climate and the Justinian plague may have created a disaster for people that was even greater than the Black Death,” Ljungqvist thinks. He has published a popular science book in Sweden, Klimatet och männskan under 12000 år, (Climate and Man over 12,000 Years).

Ljungqvist also co-authored a research article in 2016 in the journal Nature Geoscience. Here the researchers used the name Late Antique Little Ice Age to describe the period from 536 to 660.

A dramatic transition

In Norway, the centuries before the year 550 are called the Migration Period. The time after 550 and up to the year 800 is called the Merovingian Period. Then comes the Viking Age.

The transition from the Migration Period to the Merovingian Period around the year 550 also marks the transition from the older Iron Age to the younger Iron Age.

The catastrophe thus occurred in the transition between the Migration Period and the Merovingian Period, and in the transition from older to younger Iron Age.

This is transition where researchers — as you probably already have understood —have suspected for some time that something dramatic must have happened.

Now we know what this dramatic happening was.

The graves that disappeared

Here are some other indications from Norway of the disaster from 1500 years ago:

In Norway, the number of burial finds at the beginning of the Merovingian Period falls by at least 90 per cent, compared with the number of finds from the Migration Period. To repeat: This was the time before and after the disaster.

This change could certainly be due to new burial customs. But an equally likely cause is the combined effect of the volcanic eruptions in 536 and 540, and the Justinian plague.

In Denmark, archaeologist Morten Axboe found that large quantities of gold and other precious metal jewellery were sacrificed right after the climate shock.

Axboe's theory is that these sacrifices were actions of desperate people. They sought to mollify higher powers and asked them to bring the sun back into the sky.

A strangely quiet time

An article about the Merovingian Period (550-800) on Norgeshistorie.no is entitled “Hundre års tystnad,” which translates as “A hundred years of silence.”

Per Ditlof Fredriksen is an associate professor at the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History at the University of Oslo and authored the article.

Fredriksen calls the first part of this historical period a strangely quiet time in Norway. Like Iversen at the Museum of Cultural History, he points out that from the years 550 to 650 there are very few archaeological finds in Norway.

It’s not just that people stop building houses and burying their dead.

It also looks like people are forgetting how to make important tools. Tools they definitely needed.

It is only beginning around the year 650 that archaeologists see that human life in Norway was once again beginning to return to normal. But then much of the technology was new. A lot of knowledge had obviously disappeared. For example, people started making iron in a whole new way.

In Rogaland and the surrounding areas, until the disaster 1500 years ago, there were many skilled goldsmiths.

Both they and their craft disappeared.

The same thing happened to the many talented potters who had lived in western Norway before the Merovingian Period, from Jæren in the south to Sogn in the north.

It would take another thousand years before equally fine pottery was made in Norway.

Which volcanoes were they?

The clearest indications that there were two different volcanic eruptions in succession that created the Fimbul winter are from ice cores obtained from inland ice sheets on Greenland.

Some researchers have suggested the Ilopango volcano in El Salvador as the cause of the first disaster in 536. Another alternative is Krakatau in Indonesia.

Instead, Ljungqvist thinks El Chichón in southern Mexico was the most likely cause, based on what researchers know today.

In 1982 it turned out that El Chichón is still a deadly volcano. An eruption at that time cost 2000 people their lives. Prior to this, the volcano had not erupted since 1360 and people were not prepared for the sleeping giant to wake up.

There’s little doubt that aerosols released by volcanoes into the atmosphere can affect the Earth's climate today.

The higher in the atmosphere the aerosols reach, the longer the effect will last. What is probably decisive is whether the aerosols reach the stratosphere, or altitudes over 10,000 metres — which is the altitude where most of the air traffic is.

Huge volcanic eruptions are not uncommon

The United Nations Climate Panel (IPCC) wrote in a report from 2013 on how climate change over the last 2000 years may have been affected by volcanoes. Much of the knowledge researchers today have about the effects of volcanic eruptions back in time comes from ice cores gleaned from Greenland and Antarctica.

The researchers behind the IPCC report found that there have only been two or three hundred years since the Viking Age without very large volcanic eruptions that have affected the climate significantly.

The fact that the whole of the last century — the 20th century — was without gigantic volcanic eruptions may have helped make this be something that few of us imagine could happen again.

But it will certainly happen again.

Giant volcanic eruptions that affect the climate over a long period are actually not very rare.

It’s common for the climate and temperature of the Earth to be affected for one to three years after a huge volcanic eruption, depending on the number of aerosols that reach far into the atmosphere.

If several such gigantic volcanic eruptions were to occur in succession — as they probably did in years 536 and 540 — the impact on the climate would be even greater.

If this happens again, there are a lot more people on Earth who will need food.

On the other hand, society is much better prepared for this kind of disaster. We can transport food and mostly everything else we need over long distances. The people who lived in cold Norway 1500 years ago couldn’t do this. They were completely dependent on the food they grew and the animals they raised themselves.

1816 was "The Year Without Summer"

The year 1816 has become known as "The Year Without Summer".

It was an unusually cold year in Western Europe and the eastern part of North America. There was also an unusual amount of rain. In the spring after — in 1817 —grain prices in parts of Europe doubled.

The main cause of the unusually cold summer of 1816 was the explosion of the Tambora volcano in Indonesia. But in the years before the Tambora eruption, there had been four other major volcanic eruptions, all of which had spewed a lot of dust into the atmosphere.

The natural disaster in 1816 was hardly of the same magnitude as the disaster of 536. It was nevertheless severe.

It is therefore worth noting that the consequences were not at all the same. Two hundred years ago, the world was becoming modern.

In 1816 there was extensive international trade. Ships could carry a lot of food. People in distress could go to America, and many left. Several countries had a kind of social welfare system in place that could help the very poor. National health care systems and most people had become much better at preventing plague epidemics.

If we are again struck by a disaster like the one that happened in the 500s, we would be much better equipped to face it.

A lot of scientific articles will be written about what happened. Many will write books. Millions will tweet or post on Facebook.

Many of us nevertheless still believe in myths.

But we are unlikely to ever experience a Fimbul winter again.

———