A reindeer hunter lost this knife in the Norwegian mountains 1500 years ago

“It’s incredibly well preserved”, says archaeologist Lars Pilø from Secrets of the Ice.

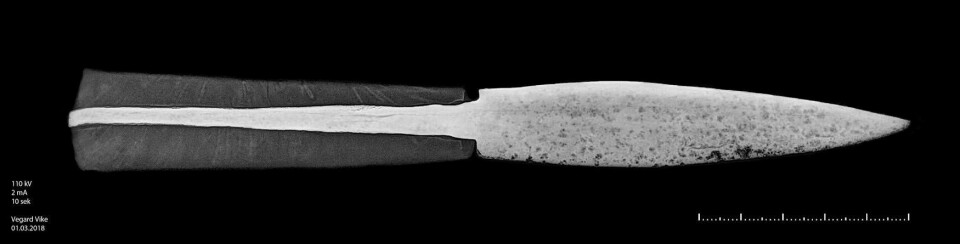

Beautifully carved out of curly birch, the burl handle of the knife and the rusty blade melted out of the ice just a few years ago.

It’s 1500 years old. But it looks as though it could have been in use last season.

“There’s something about it, you can just sort of visualize the person who used it to butcher a recently killed reindeer”, says glacial archaeologist Lars Pilø.

“And then somehow they lost it or forgot it. It’s something you can relate to, you know. Something that could happen to any of us out hunting today”, says Pilø.

The Trollsteinhøe site contained the usual suspects from a reindeer hunting location up in the Norwegian mountains: scaring sticks (used to manipulate the reindeer into position), arrows, hunting blinds, antlers and bones.

And then this gem of a find, a perfectly preserved knife.

Perfect conditions

At 2100 metres, Trollsteinhøe in the Jotunheimen Mountains is the highest site surveyed by the team of Norwegian archaeologists who make up the Secrets of the Ice programme in Innlandet county.

“This is an especially high altitude, it’s extremely cold and dry”, says Pilø.

It’s these conditions that preserve thousands of years old items so well.

During the first surveys of the site, all the items found were dated to around 1500 years ago, in the 5th and 6th century AD. The first finds here were discovered in 2011. After 2019 however – when a very warm summer melted away larger parts of the ice patch, even older items appeared, a 4000-year-old arrow from the late Neolithic as well as two arrows from the Bronze Age (3000 years ago).

“Items from the Bronze Age and the Stone Age are often buried further into the ice than the stuff from the Iron Age”, says Pilø.

All the new finds compelled the team to write a new internal report on the site, summed up by a series of posts on the programme’s popular Facebook page.

Lots of sticks for a tiny site

The tiny ice patch at Trollsteinhøe revealed an impressive number of scaring sticks – 362 in total.

At another site the team recently published a report on, Sandgrovskaret, a mere 32 sticks were retrieved.

The sticks were used to manipulate the easily scared reindeer into positions where they could be shot and killed with a bow and arrow.

Three other sites in addition to Trollsteinhøe have contained several hundred such sticks.

Why so many scaring sticks in one spot, and hardly any at another?

“Let me just say this as it is: there’s a lot of stuff we don’t fully understand yet”, says Pilø.

One theory suggests it has to do with the landscape. Some sites, where the landscape is open, would have required scaring sticks in order to enable the hunting. This is however not quite true for Trollsteinhøe.

Another possible explanation is that the large amounts of sticks might have been lost when a few hunts have been surprised by bad weather.

“Say if you had placed 200 sticks in a few lines in the snow, and then you got bad weather, early snow – this can happen in August in these heights. You had to leave, and your sticks were lost in the snow”, says Pilø.

“So it could be due to functional reasons, or just by chance”.

Three of the woollen threads on the scaring sticks have been dated to the 5th and 6th century. The pine wood has been dated to the 3rd century – but Pilø believes the woollen dating is more precise. They also match the dating of the arrows found at the site.

- RELATED: People have lost arrows and other objects at this spot in Jotunheimen — for more than 6000 years

The Vikings nearly wiped them out

Starting around 536 with several volcanoes erupting and thus affecting climate all over the planet, the late antique little ice age made life hard in the cold north.

“Our finds from the mountains show that this worsening of the climate, which must have made regular agricultural activity very difficult, led to increased hunting activities”, says Pilø.

Up until the Viking Age, the hunting was largely a sustainable activity. The number of hunters and kills did not affect the animal population.

“At this point in time a Northern-European market for trading in reindeer skin and antlers was established”, Pilø says.

This caused the hunting to completely change character. The Vikings established mass hunting facilities where they could collect and kill hordes of reindeer for export.

“Other studies from this area in Norway have shown that something happens to the genetic material from the animals during this time. There were few animals left, and it seems as though the mass hunting made a substantial dent in the animal population”, Pilø says.

Going off piste to find the Stone Age

So far, the Secrets of the Ice project has mostly surveyed sites that they know have been connected to farms down in the valleys. This makes sense if you only go a couple of thousands of years back in time.

The same farms, however, might not have been relevant for the Stone Age or Bronze Age hunters.

“They might have used this landscape in totally different ways. Areas that we today consider as totally remote might not have been so during that time”, says the glacial archaeologist.

Bound by resources, exploring areas that are difficult to access and full of snow is not always possible to prioritize. But it’s certainly on the wish list.

The tiny ice patch that is Trollsteinhøe will most likely soon be no more.

“The ice in the Norwegian mountains will largely disappear during this century”, says Pilø.

“That’s the dramatic and less nice background for all of our exciting finds”.

------