People have lost arrows and other objects at this spot in Jotunheimen — for more than 6000 years

Archaeologists have found many artefacts here in recent years. What do these finds tell us about the people who hunted here thousands of years ago?

For many thousands of years, people have gone up to snow and ice patches up in Jotunheimen to hunt reindeer with bows and arrows. Jotunheimen, which translates as “Home of the Giants”, is a mountain area in mid-southern Norway containing the country’s highest peaks.

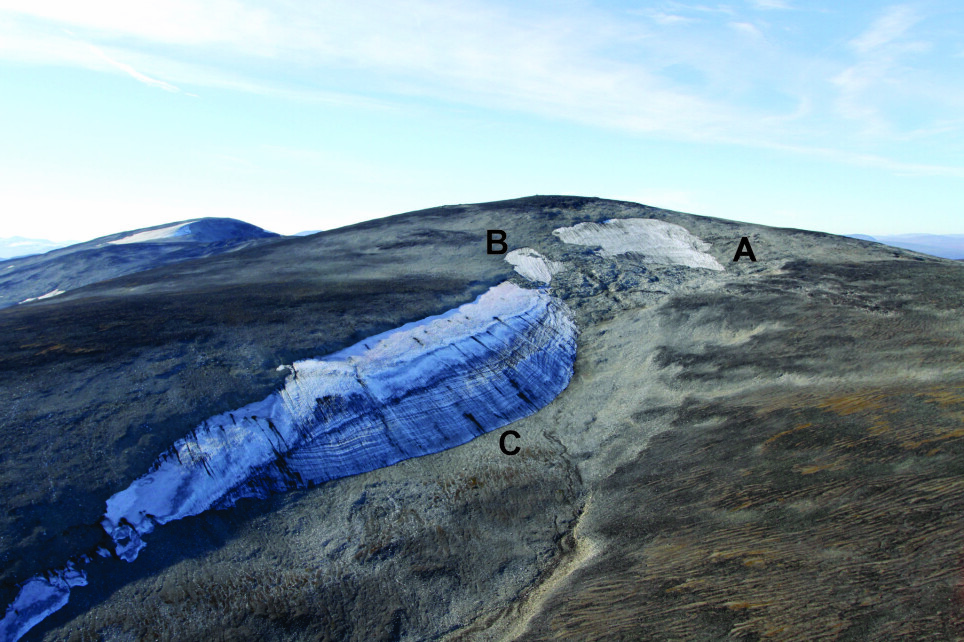

One of these areas is called Langfonne, which sciencenorway.no visited in 2016 with archaeologists from the former Oppland County Municipality, now called Innlandet.

As the ice melts away in the Norwegian high mountains, more and more objects that have been used and lost by people are revealed by the retreating ice. The ice can act as a time capsule, preserving things that would otherwise weather away.

Among other things, archaeologists have found a more than 3,000-year-old, almost completely intact leather shoe here, and several other objects both here and at other ice patches.

The method the researchers use is mainly to conduct a systematic hunt, by visually searching for objects that have melted out of the ice.

And what archaeologists find most at Langfonne are arrows.

In the summer, reindeer come up to the snow to escape reindeer warble fly — an insect that lays its eggs in the reindeer's skin, nose and throat. These eggs hatch, and larvae begin to live in the animal.

People have exploited the reindeer’s habits to hunt them when they are up on the snow. Archaeologists have found almost 70 arrows here, and carbon dating of the arrows shows that their dates span a lengthy period: The oldest are around 6100 years old, while the newest are from the 13th century AD.

“We see that they are getting better at making arrows. They go from using straight branches to make arrows, to making arrows of higher quality from split wood. We can see arrowhead technology evolving,” Lars Pilø says to sciencenorway.no. Pilø is an archaeologist for the Innlandet County Council, and has worked with glacier archaeology for more than ten years.

“But there is an enormous amount of continuity in these finds. Basically, people have been engaged in the same kind of hunt for centuries,” he said.

But what do the finds tell us? In a new research article published in the journal The Holocene, archaeologists have tried to piece together a larger story, and to put the findings in context.

They may have found evidence of an increase in reindeer hunting that may be linked all the way to the import market in Denmark in the 700s — during the early Viking Age.

But while these objects can be pretty well preserved over a long period, nature nevertheless poses challenges for the archaeologists.

Ground up by ice, bad weather

“This site differs so enormously from other archaeological sites in the lowlands,” Pilø said to sciencenorway.no.

While archaeologists have practiced their craft with archaeological digs for a long time, and know the processes that allow objects and evidence of people to be interpreted and put in context with other surrounding finds, glaciers and ice patches are something completely different.

If archaeologists find many things from a particular time period, does that mean there were more people there and thus more things from this period, or is it only that conditions on the mountain have allowed these objects to be preserved?

Arrows, clothes or anything that has been lost on the ice can lie untouched for a long time before the ice and snow melt, and can then be re-frozen into the ice and melt out repeatedly, until the process destroys them.

When it is warmer in the mountains, meltwater can form small streams over the ice, which can carry objects down to the terrain.

Those conditions can mean you end up with a mashup of discoveries, as Pilø calls it, where arrows made several thousand years apart end up in the same place. The objects may be well preserved, but much of the context is gone.

At the same time, the ice inside the ice patch also moves. Langfonne is not a glacier, but is rather an ice form that has built up over many thousands of years. It’s probably around 7600 years old, Pilø said. There is so much movement in a glacier that objects are crushed over a relatively short time. The ice patches themselves also move, only much slower than glaciers.

All this movement can crush arrows and other objects from specific time periods. At the same time, things that have melted out are exposed to strong winds and weather in the high mountains before archaeologists can find them.

“So the question is: Are the exciting patterns we see just due to natural phenomena?” Pilø asks.

Pilø emphasizes that archaeologists must be very careful when interpreting these finds, but that they nevertheless believe they can draw some conclusions.

Bone combs and reindeer hunting

The researchers have looked at how the finds are distributed over time, and which periods stand out.

Very many of the arrows date from between the 3rd and 13th century AD, with a peak around the year 750. This is the very beginning of the Viking Age, where hunting reindeer may have become more interesting from an economic standpoint, and thus may have drawn more hunters to the mountains.

“We know that reindeer antlers became economically valuable at this time, and that there was a market for them outside the region,” Pilø said.

Pilø points to finds from a Viking marketplace in Ribe, Denmark from the 8th century. Elegantly carved combs made from reindeer antlers have been found there, indicating that this was an export item, according to this article from The Guardian. No one knows yet where these antlers came from.

But why do archaeologists believe this may be a period when many things were actually lost due to increasing hunting, rather than just randomly conserved?

Archaeologists have also collected antlers and bones from reindeer. Reindeer drop their antlers as they grow, and the antlers are also preserved in the ice.

The antlers from the ice patch have also been radiocarbon dated. By comparing the dating of the objects and antlers and bones from dead animals, the researchers believe they have found a pattern.

There were almost no antlers from the same period as there were most arrows. This may mean that the entire animal, with bones and antlers, was systematically removed from the ice during the same period as there may have been more hunting, according to the research article. Hunters may also have collected antlers that the reindeer had dropped naturally during this period.

Pilø argues that this may be a real pattern, meaning that the finds reflect a period when there were more people and more hunting there.

“Evidence of more intense reindeer hunting at this time can also be found elsewhere, such as remains of larger trapping facilities,” he said.

But other patterns may be more difficult to explain.

A 1400-year break?

The oldest arrows date from around 6100 years ago. But of all the objects that have been dated so far, archaeologists have not found anything that dates from a 1400-year-long period, between 5700 and 4350 years ago.

“We believe that the earliest finds have been exposed from ice movements,” Pilø said.

But then there is a long period without any finds. This does not necessarily mean that people took a 1400-year break from hunting on Langfonne, however.

Pilø says they have finds from other ice patches that indicate there was hunting during the same period from when there were no finds from Langfonne.

“The arrows from this period may still be hidden in the ice,” he said.

At the same time, if there were recent discoveries still to be found in the old ice up on Langfonne, it’s strange that the earliest arrows have already melted out of the ice patch.

“This is something we don’t fully understand,” Pilø said.

The ice in the Norwegian mountains surely still contains a number of objects from several thousand years ago.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

Reference:

Pilø et al: Interpreting archaeological site-formation processes at a mountain ice patch: A case study from Langfonne, Norway. The Holocene, 2020. DOI: 10.1177 / 0959683620972775.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no