7,000-year old fish traps excavated in Norwegian mountain lake – a race against time as the water is coming in

Four Stone Age fish traps were discovered by chance in the Norwegian mountains last summer. Archaeologists are now working against the clock to secure finds before the area is again covered in water.

In the seabed of the mountain lake Tesse in Jotunheimen, 850 metres above sea level, archaeologists from the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo (KHM) are digging as fast as they can. Towards the end of this week, all traces of the 7,000-year-old fish traps will be covered by water again.

The water in Tesse is drained every year to produce power, but quickly fills up when snow and ice in the mountains melt.

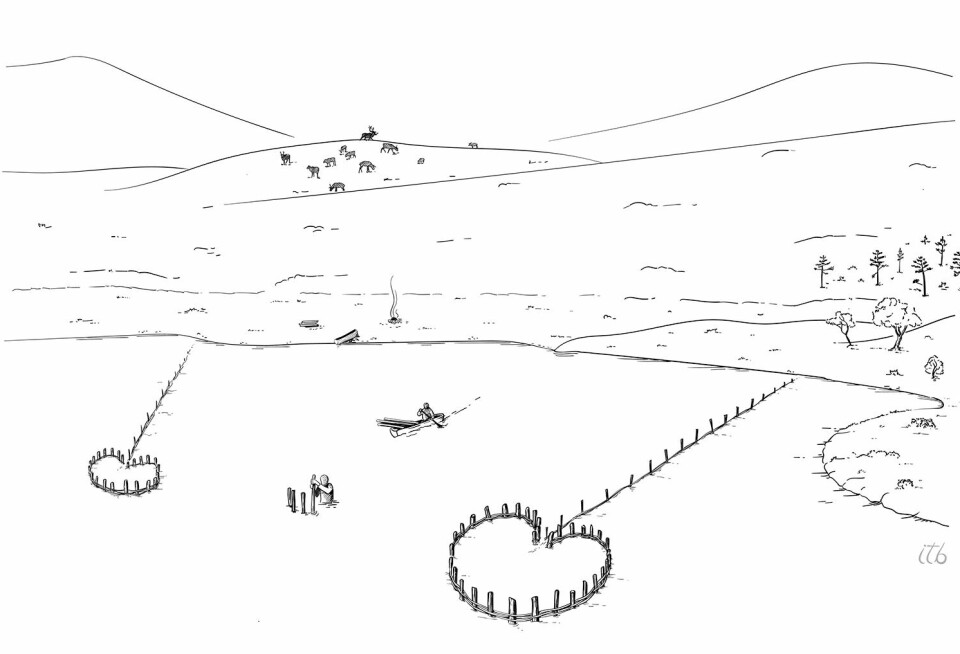

The four fish traps discovered by mountain hiker Reidar Marstein last summer consist of long poles that have been driven into the seabed. They form the pattern of a fence that has guided the fish into a chamber. From there, Stone Age folks could easily use a fishing net to catch the fish they needed.

"They have worked really hard to get them into the seabed"

“The poles are pointed at the end and were clearly driven into the seabed with quite a bit of force,” says Axel Mjærum, archaeologist at KHM and project manager for the excavation.“The pointed ends are slightly damaged at the tip, so we can see that they have worked really hard to get them into the seabed.”

Each chamber consisted of around 40-50 poles, and the archaeologists have found remains that are as much as 80 centimetres long. They are so well preserved that they ‘might as well have been cut last year’, they write enthusiastically on KHM's Facebook page.

In the Norwegian mountains, archaeologists mostly find stone objects and animal bones from the Stone Age. Processed wood from this time period has hardly been found before.

“Here we can also see how the wood has been designed,” Mjærum says.

“Actual traces of axe chopping from the Stone Age is something we almost never find in Norway otherwise.”

Perhaps the archaeologists will be able to find out what kind of tools were used to process the poles. In fact, perhaps they already found them, during previous excavations up here.

Found by the man of the mountain

At first, this year’s excavation needed to determine whether the poles Reidar Marstein found on that mountain trip last summer were in fact ancient fish traps. Mountain hiker Marstein also goes by the name of a hobby archaeologist. It is not the first time he has found unique archaeological objects in the Norwegian mountains.

“He is a man of the mountains who walks anywhere and everywhere, and he has found many of the ice patches where the glacial archaeologists in Innlandet county have discovered so many exciting things in recent years,” says Mjærum.

This time too, Marstein hit the mark.

“We were quite sure that we were dealing with fish traps here, but now we are absolutely certain,” says Mjærum.

It was known from earlier archaeological finds that building fish trapping chambers in this style to catch fish is an old tradition. The Tesse find is still remarkable, according to the archaeologists, because it is so very old. It is perpahs the oldest fish trapping facility of its kind ever excavated in northern Europe.

Mountain fishing for thousands of years

Last year, the archaeologists only had one carbon-14 dating, a wooden pole dated to 5,000 years BC. This year, more test results are available, which show that people also fished here in what is called the Neolithic Age, 3,700 years BC.

“Our impression now after being up here, is that this is even more complicated than that and that we will find traces of even more time periods,” says Mjærum.

This is one of the things about the find that makes it so special, according to the archaeologist.

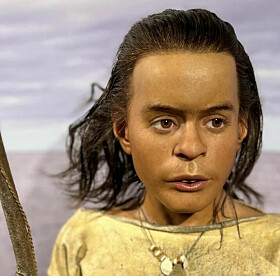

“It’s a find that brings us very close to the Stone Age people. Not that we can see an individual's work, but through the studies that we now have the opportunity to do on this amazingly well preserved wood, we will learn if they have been there many years in a row and when and how they have maintained the traps. It will give us detailed knowledge about the use of the mountain that we have been missing,” he says.

“A big question is whether they have used these dwellings for many seasons or whether they were only there once or a few times.”

Finding the answers to this in dendrochronological studies of the wood will give more reliable results than the carbon-14 datings that currently exist, which have higher levels of uncertainty.

Enabled the reindeer hunting

Stone Age people came to the mountains to hunt reindeer. The glacial archaeologists in Secrets of the Ice, from Innlandet County Municipality, have found extensive traces of reindeer hunting taking place over thousands of years. The older the ice that melts, the older the arrowheads.

Engaging in fishing up here as well may have functioned as a kind of reliable food supply, Mjærum believes.

“Fishing is safe and predictable. Hunting reindeer with a bow and arrow is perhaps more prestigious, but also more unpredictable. It is not the fish that have drawn these people to the mountains, they also had fish in the lowlands. But the fish have made it possible to engage in reindeer hunting, which we know has been important to them,” he says.

Mjærum believes that the work may have been organised in such a way that while some went hunting and trapping, others took care of the fishing.

“Perhaps this was a job for children and parents, who were not involved in the hunt itself,” he suggests.

The Vikings also fished here

In 2013 and 2014, there were extensive excavations around Tesse. The area was mapped, and Stone Age settlements were found around the entire bay where the fish traps are located.

That fishing in Tesse has been important is well known from other historical periods. Until it became a site of power production, this has been one of the mountain area's richest trout waters with exceptionally good fishing way back in time, according to Mjærum.

Archaeologists have found thousand-year-old net sinkers here that the Vikings used for net fishing in Tesse. Perhaps to secure food while they herded reindeer into their trapping facilities.

And a diploma from the Middle Ages testifies to disputes over fishing rights up here. The diploma establishes that farmers in Garmogrenda in Lom have the legal rights to fishing in Tesse.

Why didn't the archaeologists find the fish traps in the water at that time almost ten years ago?

“Firstly, archaeologists find what they are looking for,” Mjærum says.

“When we were there at that time, we looked for other things and made some great discoveries.”

In addition, Tesse is a large lake, and the closest searches for finds on the seabed took place around 50 metres away from the area where the fish traps are located.

More aware of fishing

Something has also happened in terms of the attention given to the importance of fishing during the Stone Age. They didn't just hunt and gather, they hunted, gathered, and fished.

“One reason for the lack of awareness on this is the archaeological material,” Mjærum explains.

Arrowheads are easy to detect. Fishing gear is often made of wood and bone and rots away.

“But in recent years, archaeologists have become better in the field and have acquired new methods. So when Marstein comes here in the summer of 2022, he is now more aware of fishing. And he is also a very knowledgeable man who knows a lot about archaeology,” Mjærum says.

Probably fishing like this also along the coast

Knut Andreas Bergsvik is a professor of archeology at the University of Bergen. Among other things, he conducts research on hunters and fishermen on the coast of Norway during the Stone Age.

Bergsvik, who is not involved in the excavation in Tesse, agrees that it is a pretty sensational discovery.

“We have believed that Stone Age people used different types of advanced fishing facilities. Clear indications of this have been found in Denmark and Sweden in recent decades. But this is the first time something like this has been discovered in Norway,” he says.

From the coast, it is well known that Stone Age people did a lot of fishing. At several of the settlements there, fishing tools and fish bones from many different types of fish have been found, Bergsvik says.

“The fish traps in the mountains tell us that this is something they did up there, but it also tells us that they have probably done this along the coast too, with controlled catching of fish in such facilities. The advantage of fish is that if you have the equipment to catch it, it represents security in life. Even if you don't manage to hunt and catch reindeer one day, you can eat fish. The fish has been a financial security to fall back on, and it has probably been incredibly important to have that kind of security."

More to come

This year's excavation in Tesse is coming to an end. Of the four fish traps, the archaeologists have concentrated on excavating one of them properly.

"Then we have one year to conduct analyses and obtain results, and then we will see what we do next," says Mjærum.

Perhaps the archaeologists will also be there the next time the water is drained.

“There are still important things in the ground that it is possible to do further work on.”

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no