Mysterious medieval moat found in the middle of Oslo: "Could suggest a desperate need for defense"

An untouched area of land in the middle of the city presented a puzzle to the archaeologists. Until they realized what it was: King Haakon Haakonsson’s moat. But why did the King build what was by then an outdated defense system?

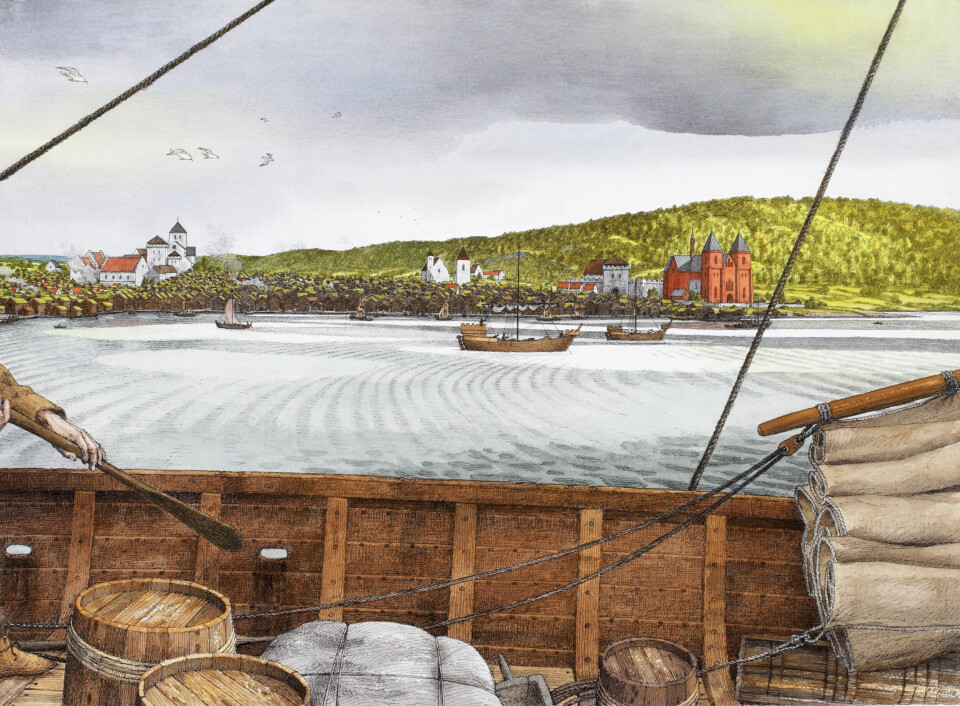

Oslo during the Middle Ages would have been a densely populated area jam packed with wooden buildings, and growing. Just southeast of the city lay the royal manor.

These older parts of Oslo have been subject for excavations throughout the centuries, particularly when building railways - be it 100 years ago or during the soon to be completed Follo line.

A large area with no traces of buildings or activities between what would have been the city and the royal manor, has left archaeologists scratching their heads.

“It’s odd that such attractive areas, close to the city, were left untouched”, says archaeologist Michael Derrick from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) in a press release.

Not a random ditch

The theory that this might have been a moat was first presented in the 1990s by archaeologist Erik Schia.

Derrick is now able to confirm: “We’ve most likely settled this question – the area was not empty land; it was in use as a moat and as defense facilities for the royal manor.”

In a recently published article, Derrick argues that the Norwegian king Haakon Haakonsson constructed the moat around the royal manor in Oslo after the city fire in 1254.

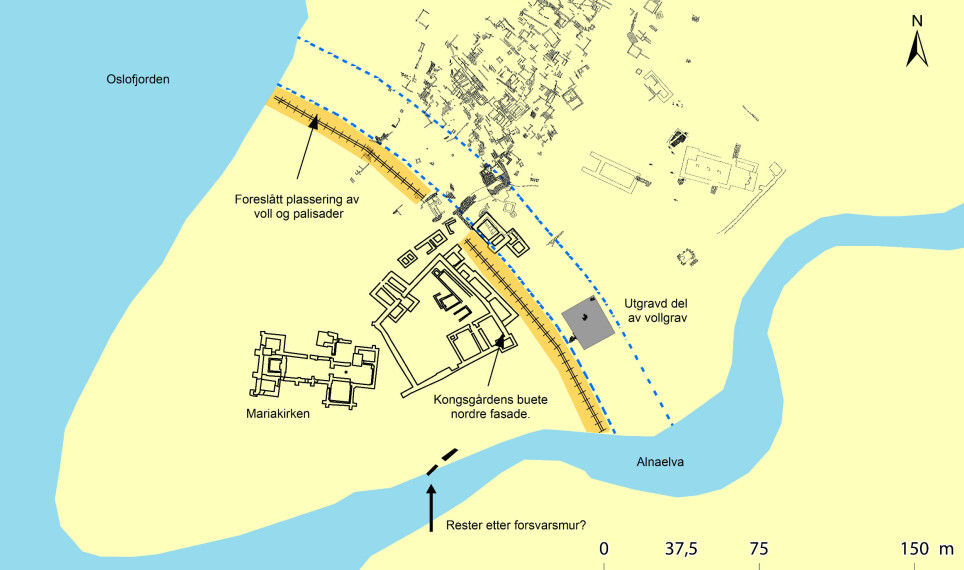

A combination of archaeological finds from the 19th and 20th century, Eric Schia’s finds of ditches in the 1990s as well as an excavation carried out in 2015 where a large ditch was found, reveal a 55 metre long empty area between the royal manor and the city centre.

When the various pieces of the puzzle were finally seen together, the image of a more comprehensive structure became apparent.

“These were not just random ditches, they were a defense system”, Derrick says in the press release.

- RELATED: Knife handle in the shape of a king from the 13th century found in the Medieval Park in Oslo

A formidable fiasco?

But who built it, and why?

Radiocarbon dating shows that it was most likely constructed between 1220 and 1260. According to Derrick’s calculations it was about 15 metres wide, and 3,7 metres deep.

“As a defense system the moat would have looked formidable. A very broad ditch with slippery and steep sides would have been difficult to cross. Add to that a mound, a palisade and an army, and you would have a hindrance that it would be difficult to get past,” Derrick says.

NIKU writes that the sagas tell tales of a royal manor not quite able to withstand attacks. When the king and his army were attacked by rival Hertug Skule in 1240, he had to retreat from the manor and to the nearby cemetery of the St. Hallvard’s Cathedral.

Oslo experienced a large fire in 1254, and archaeologist Derrick believes the moat was constructed by Haakon Haakonsson when rebuilding the city in the aftermath of the fire. The King, he believes, took this opportunity to improve the royal residence.

According to Derrick, the moat may have been inspired by defense systems in Sarpsborg and Trondheim, which included moats as a strategy for defense against attacks.

However, the archaeological datings show that it was in use for just a few decades. Some time between 1260 and 1280, it is no longer in use.

Those defense systems in Sarpsborg and Trondheim were built 100-200 years earlier. Moats were already outdated by the time one was built in Oslo.

“The moat can partly be viewed as a fiasco,” says Derrick.

He believes however, that it served as the precursor to another royal building – Akershus castle and Akershus fortress, built in Oslo in 1299-1304 – with a modern and comprehensive defense system in stone.

“The new fortress launched Oslo on the larger European scene, as a power to be reckoned with. The improvement of the royal manor was the precursor for this,” Derrick says.

Not just any king

“There aren’t many physical remains of moats around cities or royal manors in Norway, so this is an interesting find”, says Axel Christophersen, professor of historical archaeology at NTNU in Trondheim.

“We’ve thought that this is the case for a while, but now it’s been confirmed,” he says.

What remains a mystery, is why on earth Haakon Haakonsson built an outdated moat, which went out of use within a short period of time.

“It is a moat, that is for certain. And Haakon Haakonsson was involved. He was the one who used the royal manor in Oslo at that time,” says Christophersen.

“But what I don’t understand, is why he would build a moat. It was, already then, a completely antiquated defense system.”

Christophersen is skeptical as to whether Haakonsson was inspired by the old moats in Sarpsborg.

The reign of Haakonsson in Norway is known as the golden age of the Norwegian kingdom during the Middel Ages.

“Haakon wasn’t just any king in Norway. He was a king with European contacts. He was well versed in modern military defenses, and he had himself built a royal manor which we today know as Håkonshallen, The King Håkon’s Hall, in Bergen, with a massive wall around it – which was the modern way to protect a building during that time,” Christophersen says.

The moat in Oslo is certainly part of a defense system, says Christophersen, but it seems temporary in form, he suggests.

“It’s as if they had to quickly do something to protect – not even the city, but just the royal manor. Which in itself is odd,” Christophersen says.

“There’s something here which is not quite clear. There’s a story here that we don’t yet know.” He says.

Not a farm, but a royal palace

According to Christophersen, historians and archaeologists have for long imagined that the royal manors in Norway were a sort of refined farms that had simply been moved into the cities. A large farm, with nice buildings and fine architecture, that sort of thing.

He believes this description misses the point.

A royal manor in the 11th century should not be interpreted as a refined and enlarged version of a Norwegian farm, but rather as a modified Norwegian version of the royal palaces found in Europe.

“The kings of Norway, Olaf Trygvasson, Olaf II of Norway, Magnus the Good, Harald Hardrada – these Norwegian kings from the late 900s to the middle of the 1000s, they knew perfectly well what a royal residency should look like,” Christophersen says.

“They had aspirations. They wanted to be like the kings and princes of the contemporary Ottonian empire or the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in Britain.”

The first thing they had to do was make sure Norway was a Christian country. Being part of the royal European crowd was an important reason for bringing Christianity to Norway, according to Christophersen.

Then, they had to expose their regal right to be King, which was done among other ways by building the royal manors.

“We have to imagine that the royal manors in Norway were made according to the same models and systems as the royal palaces in Europe,” Christophersen says.

A recycled moat?

Written sources tell of a royal manor built by Harald Hardrada in Oslo with a sort of motte-and-bailey, says Christopheresen. A mound surrounded by a moat.

“What I am wondering, is if the moat from the middle of the 13th century, is in fact reusing these earlier moat facilities,” the archaeologist suggests.

Rather than the moat originating in 1254, as Derrick from NIKU suggests, Christophersen believes the finds of the moat should be seen in relation to the older royal manor, as it was once built in the 1000s.

“What Harald Hardrada built in the 1000s was obviously gone by the 1200s. But if you look at the walls on the northern side, it seems as though they might have built the house in relation to an older moat on the outside,” he says.

Christophersen believes that part of this old moat then might have been put to use in a pressed situation. If that is the case, then Haakon Haakonsson didn’t build an outdated moat in 1254, rather, he made an old moat wider and longer in order to solve a difficult matter at hand.

“If Haakon Haakonsson wanted to build a new defensive system around the old royal manor, he would have done so using the modern principles at the time, which was heavy fortresses with massive walls,” Christophersen says.

An interesting theory

Michael Derrick from NIKU agrees with Christophersen that the construction of the moat has a temporary feel to it, and that the reason for its construction is a mystery.

“The fact that Haakon Haakonsson chose this type of outdated defensive system could suggest a desperate need for defense, perhaps in an attempt to protect a partially constructed royal manor, or some other military emergency,” Derrick says to sciencenorway.no.

“This I believe shows Haakon to be a well-travelled pragmatic king who knew how to react in a crisis and when to abandon obsolete structures and ideas,” he says.

Christophersen’s suggestion that the moat might have been recycled from an earlier defense system is intriguing, Derrick says.

After the city fire in 1954, the royal manor would have been improved using stone as part of a big redevelopment. During excavations in the 1960s, the remains of a moat and mound were found under the stone structures of the manor. This was relatively small however, so Derrick believes it represents the remains of the royal keep – the place where people in the castle would hide if under attack.

This again would have been surrounded by a much larger bailey complex, including a moat.

“Could Håkon have recut this moat? Yes, it’s possible,” Derrick says.

“Unfortunately, any traces of an earlier moat are likely to have been obliterated by Haakon’s much larger defensive structure. Future archaeological investigation could help explore this interesting theory.”