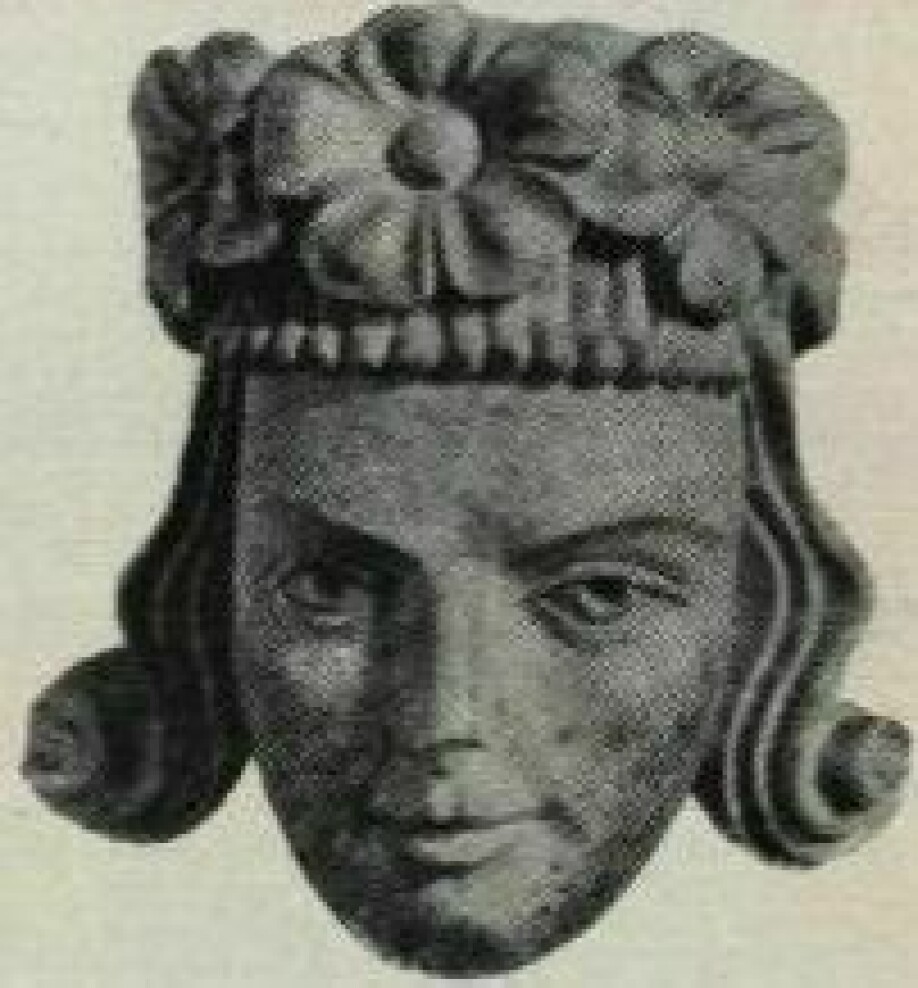

Knife handle in the shape of a king from the 13th century found in the Medieval Park in Oslo

It may be the oldest of its kind in Scandinavia, researchers believe.

The Medieval Park is located in the borough of Gamle Oslo, which literally means Old Oslo. It is a borough that can trace its history back more than 1000 years.

Archaeologists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) have since August been working their ways through the layers in order to secure traces of the past.

“We’ll keep going until March next year, so that means we’re about halfway through this dig”, says archaeologist Mark Oldham, project manager for the excavation.

On December 8, the archaeologist Ann-Ingeborg Floa Grindhaug found a small artefact, a knife handle, in the shape of a man.

The man wears a crown on his head and has a bird in his arm.

“We think it is a king holding a falcon”, Oldham says to sciencenorway.no.

Over at NIKU, the find has caused quite the stir. The archaeologists believe this may be the oldest example of an artefact depicting a falcon hunt in Scandinavia.

The knife handle is probably made of antler, according to project manager Oldham.

Easier to date royal items

Art historian Kjartan Hauglid from NIKU has dated the artefact to no later than 1250.

“The king’s robes are very typical of the first half of the 13th century”, he says.

Datings are however not always correct, he cautions.

“The artists at the time were very conservative. They often copied each other. So we have a margin of error of several generations”, he says.

Hauglid also believes that the knife handle was made for a member of a royal family. Being fashionable was most likely important in royal circles.

“This may have belonged to a royal, or a member of the higher aristocracy”, Hauglid says.

The crown has three visible holes. Hauglid believes that a ring of gold or silver might have been attached in these holes, or that the crown itself perhaps was made in a different material. It may also have been a so-called duke-garland.

Håkon V, king of Norway between 1299 and 1319, was always depicted with a garland made of roses.

MORE FROM THE SAME EXCAVATION:

- A bone and a stick inscribed with Norse runic text found in Oslo

- New runic find from medieval Oslo – this time it’s a name tag

Dating according to hair styles

There is one other Norwegian parallel to the king on knife handle. This artefact is at the Cultural History Museum in Oslo and was also found in Old Oslo. It is most likely not quite as old as the recent find from the Medieval Park.

“I believe this is slightly younger. The hair style looks a little more straight than what it did toward the end of the 1200s, the hair stuck out a bit more.”

Five artefacts from the Swedish national museum in Stockholm also spring to mind, Hauglid says. Two of the five are holding birds. These are also from a more recent date than the new find.

“They are from an old collection, and we don’t know where they were found. But they are dated somewhat later”.

Again, the hair is the giveaway.

“You can see how the hair extends out to the sides. This is the fashion in the 14th century”, Hauglid says.

Finding tiny items in large amounts of soil

The tiny artefact was found in a large area under excavation. So how do the archaeologists work in order to not miss a thing? We ask project manager Oldham.

“We’re not necessarily working to not miss something. You work at a certain tempo that gives a good balance between being able to find something at the same time as making sure that the project progresses. But archaeologists know what to look for, and in many cases can differentiate between unusual shapes, even when they dig with a mechanical excavator”, he says.

The knife handle was found in a layer of soil which most likely consists of old waste.

“You can find a lot of stuff in those kinds of layers, anything from gold rings to animal skeletons. At the same time, the things you find in layers of waste will have been redeposited, and so items from these kinds of layers of soil don’t necessarily have the same primary source value as items from for instance a grave or remains of a house”, Oldham says.

An important aristocratic activity

Falconry was not an activity enjoyed by most people, it would have been available to kings and members of the aristocracy.

“There are very few depictions of falconry in Norway. Falcons were costly and were given as gifts to other royals”, says Hauglid.

Quite a few royal falcons were given as gifts from Norway to the English royal family, according to Hauglid.

There is a fair bit more documentation of falconry from the 14th and 15th century than the previous centuries, he adds.

Falcons in 1500-year-old graves

Falconry can be traced very far back in time.

In Sweden there are 40 known finds of birds of prey from graves that date to the years between 500 and 900, historian Ragnar Orten Lie writes in spormagasin.no (link in Norewgian).

According to Orten Lie, falconry was popular among the elite in Sweden during the early Iron Age. He believes it is therefore likely that the same was true of Norway.

In 2010, bones found in the Gokstad mound were re-examined. The mound is dated to the 900s. Researcher Karin Hufthammer found bones from two goshawks.

Hunting with tame birds was supposedly widespread. Orten Lie writes that all nobility in Europe likely owned birds of prey during the Middle Age.

Up until the end of the 14th century, the Norwegian kings were active in falconry. They also had professional falcon catchers at their service, the historian writes.

Translated by: Ida Irene Bergstrøm

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no