The Norwegian medieval kings were known to give the best gifts: Falcons

Norwegian falcons given as gifts from the Norwegian king during the Middle Ages are said to have been valued more highly than silver and gold by the English royal family.

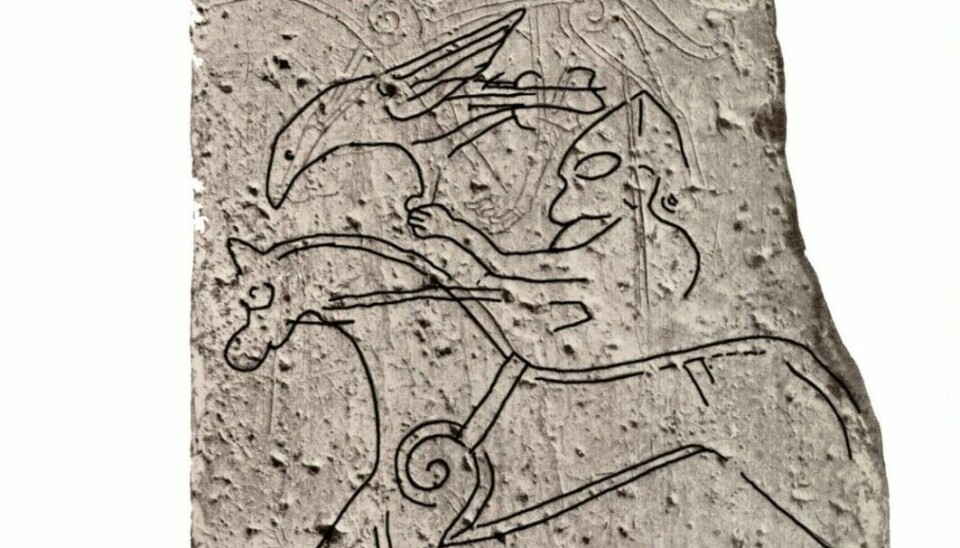

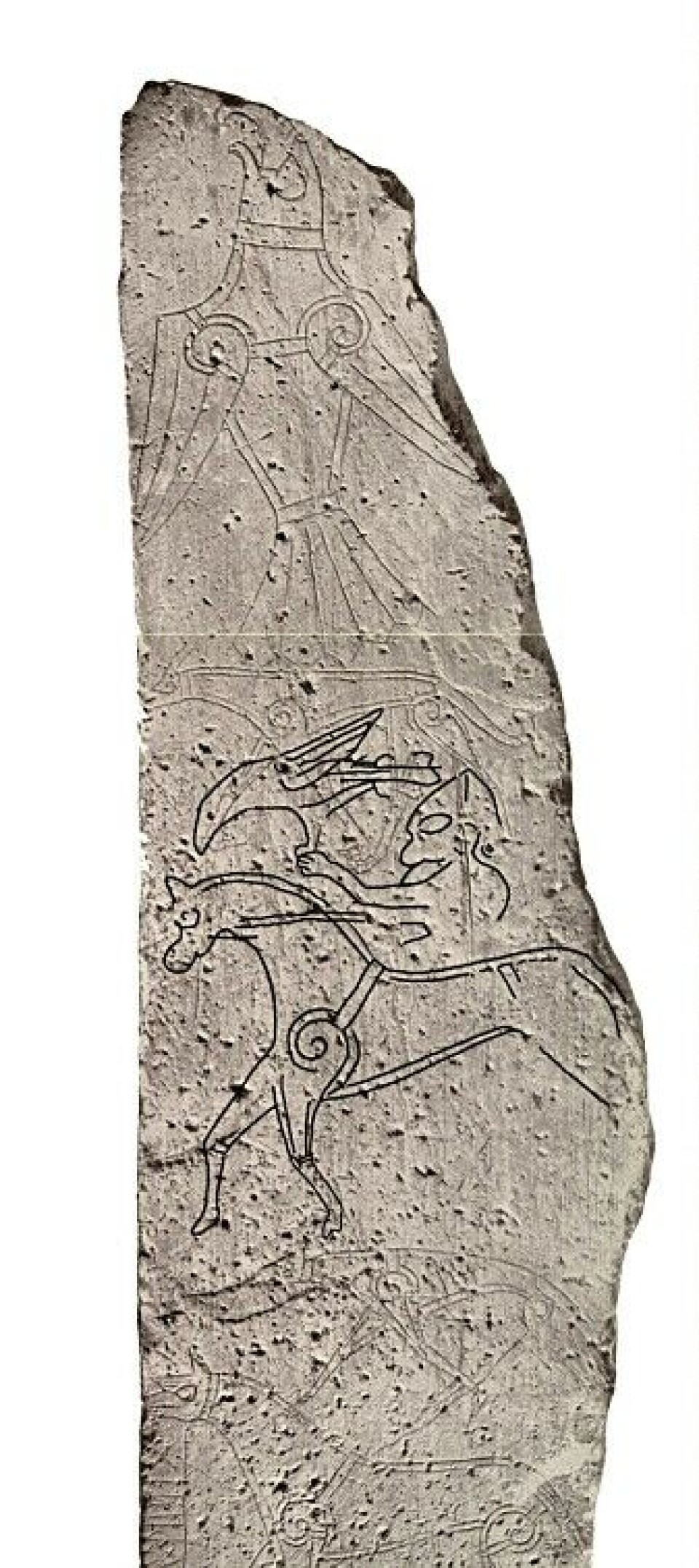

“The earliest evidence of falconry that we have is the Gokstad ship from around the year 900. The ship was used as a grave chamber and two northern goshawks were found among the grave goods. At that time, the elite were clearly the ones hunting with falcons,” says Ragnar Lie.

Lie works as a cultural heritage consultant in Vestfold and Telemark counties.

In 2021, the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research discovered a figure depicting a royal falconer during excavations in the Medival park of Oslo. The object probably originated no later than 1250.

Birds of prey were used to hunt both small game and other birds.

Although the earliest traces of falconry are from the year 900, the tradition may be older in Norway.

Phenomenon from Kazakhstan?

“Falconry probably started a little earlier,” says Lie. In Sweden you can find traces back to the 5th century.

“There’s no reason to believe that falconry didn't then also penetrate Norwegian aristocratic circles”, he says.

The phenomenon probably came to Europe in the 1st century CE. And it most likely came from the east, says the historian.

“The impulses came from the east, and the Eurasian steppe landscape is considered the area of falconry’s origin,” Lie says.

The practice might have occurred independently in different parts of the world.

Gift from royal house to royal house

That hunting with falcons was an activity for the elites has been oft repeated in books and scientific articles published on the subject.

The article ‘Norge og de britiske øer i middelalderen’ (Norway and the British Isles in the Middle Ages), written by historian Alexander Bugge in 1914, is one such example.

Norwegian and Icelandic falcons played no small role, both as export goods and as gifts, according to Bugge.

In the article, Bugge writes about so-called missions to England from the 12th to the 14th century.

“Most Norwegian missions had no other purpose than to bring gifts. Most often, the Norwegian kings sent hawks and goshawks as gifts,” writes Bugge. The gifts were to be given the royals on the other side of the North Sea.

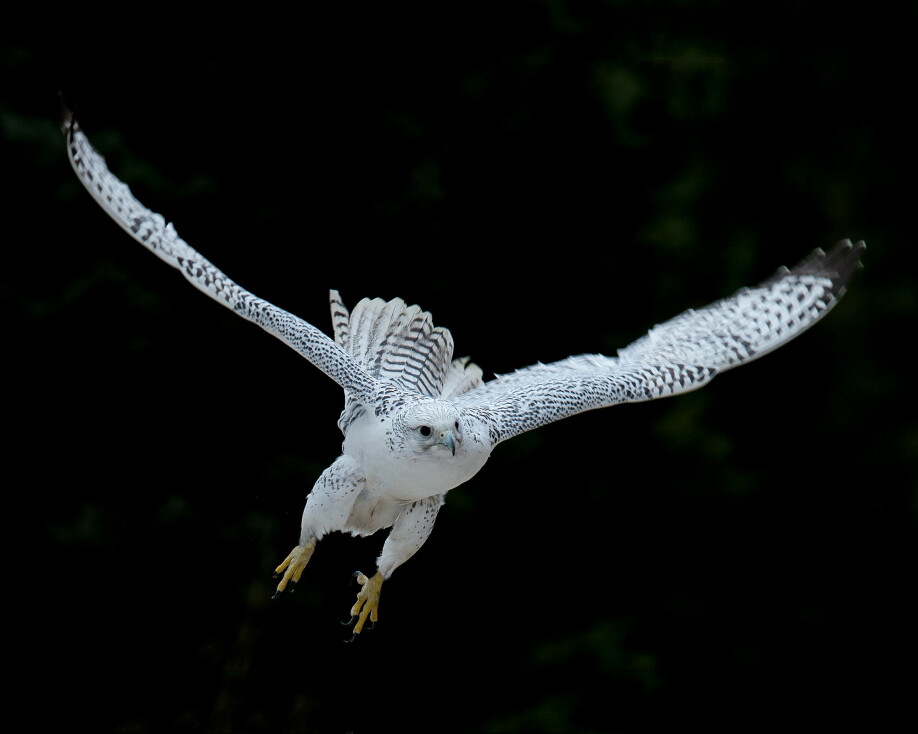

He further states that Haakon Haakonsen, who was king of Norway between 1217 and 1263, sent falconers to Iceland to capture white Icelandic falcons. These are said to have been valued more highly than silver and gold by the English royal family.

Northern goshawk most popular

Lie has also written about hawks and falcons as export goods.

Gyrfalcons were the most sought-after export item, since they were only found in northern areas and did not migrate south.

The goshawk’s status was somewhat lower than that of the falcon. But it was in many ways more convenient to use.

Whereas the bigger falcon requires large, open landscapes for hunting, the goshawk is also a skilled hunter in the forest or in cultural landscapes.

This contributed to the goshawk likely being a major export item, especially to England through the Middle Ages, Lie writes.

Only for the elite?

But couldn’t people in lower social classes also have used birds of prey as a tool in hunting?

“The evidence we have shows falconry happening among the elite. Sweden has now discovered 40 different tombs containing birds of prey from the Iron Age”, says Lie.

However, there is one element of uncertainty.

“We never find the graves of the poor. So we can’t rule out that they might have done falconry, but the activity seems to belong to the aristocratic set. And if you’re seeking status, you forbid others to do that activity. However, it could be that birds and humans collaborated for a while in connection with supplementing the food supply.”

Hunting with falcons on a large scale must also have been very resource intensive.

“You can have a goshawk and hunt for yourself, but as soon as you build an apparatus around it, the costs quickly rise to a level that few could maintain,” Lie states.

Not politically correct

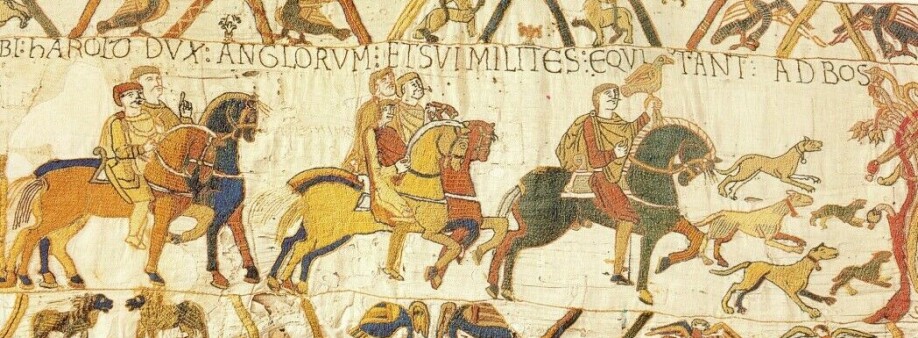

Falconry indeed became expensive when kings and noblemen went hunting. A falcon was not all that was required. Horses and dogs were often involved, you needed to have a hunting ground – and last but not least, gyrfalcon prices were very high.

“Before the French king was beheaded, people were starving while the king pursued hunting and falconry. A light went on for people that such an outrageous use of resources wasn’t politically correct,” Lie says.

King Louis XVI was beheaded in 1793. After the 17th and 18th centuries, the king was no longer to lead troops into battle. And the king who trained for hunting and achieved social status through hunting, disappeared.

Falconry became much less visible in society, and the tradition faded in Europe.

During the 18th century, the aristocratic use of birds of prey declined dramatically.

Waste or duty?

Even well before the French Revolution, falconry was viewed with a critical eye.

The church believed it was both a waste and a vanity. Ragnar Orten Lie and Frans-Arne Stylegar write about this in an article in the magazine Primitive Tider (Primitive times) in 2021.

The nobility came back with no shortage of counter-arguments. They argued that hunting was training for war – and that training for war was a duty. He who hunts does not sin.

In the 12th century, this type of hunting achieved a slightly different status, the authors write. Big game hunting remained raw and brutal. Falconry becomes a more sophisticated form of hunting that requires more knowledge.

From high status to total irrelevance

Many birds of prey were persecuted and hunted throughout the 19th century and parts of the 20th century, the Norwegian organisation Birdlife writes on its website. Several species were on the verge of extinction in the mid-20th century.

Lie believes falconry’s fluctuating status through the ages shows an exciting development. From being symbols of high status, birds of prey went on to be considered a nuisance.

Birds of prey were lumped together as being in competition with humans for the prey.

Employing shotguns, a war of extermination was started against birds of prey. Eggs were broken and young birds killed.

On top of that, acid rain entered the scene in the 1950s, 60s and 70s. Eggshells became fragile and broke during incubation. The result was that few young made it to adulthood.

In 1971, however, several species of birds of prey were protected.

“Once they’re protected, there’s absolutely no question of falconry in Norway anymore,” says Lie.

The population of many species has increased in recent decades. But some are still struggling, writes Birdlife, including sea eagles, ospreys and peregrine falcons.

More historically relevant than many are aware of

“What’s fun about working with the phenomenon is that it has great cultural-historical relevance,” says Lie, who has studied falconry since 1999.

He finds it especially exciting because many are not aware of how widespread falconry was in Norway during the Middle Ages.

There are also important environmental issues associated with hunting with these birds, says Lie, especially since the tradition is on its way back in some countries. In Norway it remains illegal.

In Denmark, however, falconry is legal for show.

In countries like the United Arab Emirates, gyrfalcons are even required to obtain their own passports. This came in handy when a Saudi prince booked airline tickets for his 80 falcons. Aftenposten wrote about this in 2017 (link in Norwegian).

The tradition of falconry can put pressure on the population of the birds of prey that are used. The female birds are slightly larger than the males, and thus more popular.

But many falconry groups are serious, and the cooperation between the environmental side and falconers is positive, says Lie.

Reference:

Lie, Ragnar Orten and Stylegar, Frans-Arne Hedlund: Veidekongen, olifanten og bøkeskogen (The Hunter king, the olifant and the beech forest): Hunting, war and aristocratic ideology in the Viking Age and the Middle Ages. Primitive tider, 2021. (Summary)

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no