Now we know who the Vikings had children with

DNA evidence from Norway points above all to Britain and Ireland rather than people from the north-east. But a lot of this hereditary material has mysteriously almost disappeared after the Viking Age.

The Vikings had a lot of contact with the different people around them. Many came from foreign lands to Norway, Sweden and Denmark.

Genes flowed into Viking society from the west, east, south and north-east – in line with whoever the Scandinavians of the time had children and formed families with.

Now a group of researchers from Iceland and Sweden have collected all genetic analyses that have been done of Vikings.

They have compared these with the genes of today's Norwegians, Swedes and Danes.

Today Norwegians have genes from the west and north-east

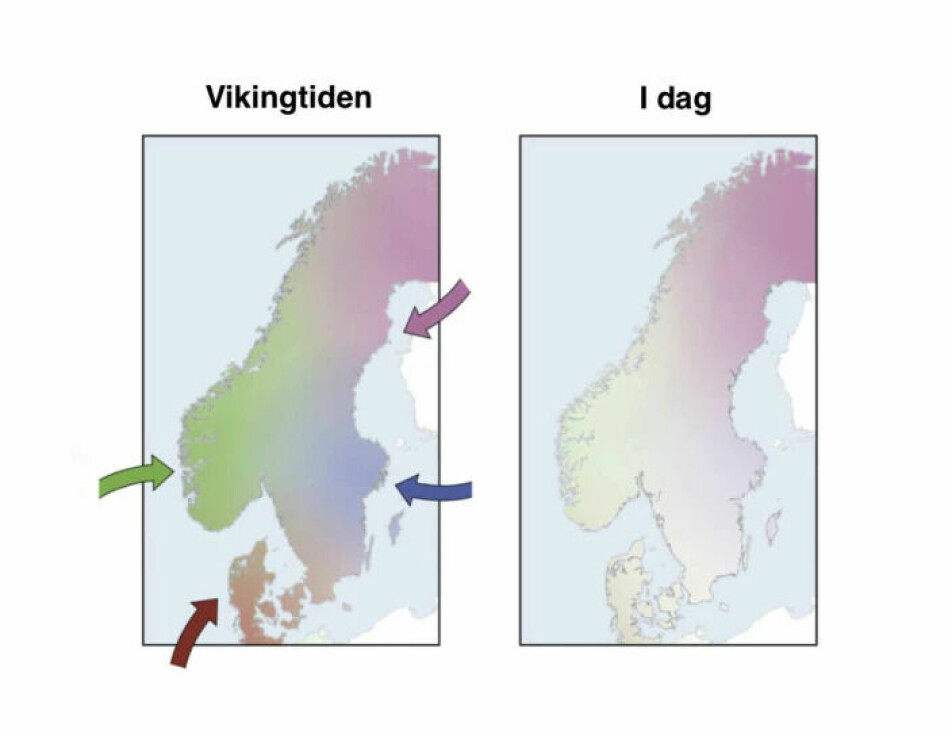

The map below on the left is a sketch of how genes from other peoples flowed into Scandinavia during the Viking Age.

The genes that came to southern Norway and central Norway came above all from the west (green arrow), from Great Britain and Ireland.

They came to Denmark from the west and south (red arrow). They came to central Sweden from the east (blue arrow). The genes that came to northern Norway and quite far down in Sweden came from people in the north-east.

The map to the right shows how traces of genes from Britain and Ireland are still found (light green) in Norwegians with origins in southern Norway.

The researchers found the same genetic traces from people in the west in today's Danes and quite far into Sweden.

In northern Norway and much of the rest of Sweden, it is above all Uralic genes from the north-east that can be traced in the genetic material of today's people.

But why has the genetic evidence of the people who came from the east and south more or less disappeared from Scandinavia?

The genes of 297 people from the past

A new study published in the life science journal Cell describes how researchers in Iceland and Sweden examined the genes of Scandinavians over the course of nearly 2,000 years.

The researchers collected DNA analyses from studies of a total of 297 people who lived in Scandinavia from around the year 0 until the 17th century.

A majority of these lived during the Viking Age, approximately 750-1050 CE.

The researchers compared these analyses with the DNA of 16,000 living Scandinavians, of whom just over 7,000 were Norwegian. They also compared this information with DNA from people who now live in the rest of Europe.

Found something strange

The most important findings reported by the researchers from the deCODE Genetics/AMGEN institute in Reykjavik and Stockholm University are:

- Vikings went east to today's Russia and Ukraine, to the Baltics and all the way down to Byzantium. The researchers found traces of genes from these areas above all in people who lived during the Viking Age on Gotland, around Stockholm and in the Mälardalen in central Sweden. But these genes from the east quickly began to disappear from Scandinavian DNA after the Viking Age. Why did this gene component disappear?

- The traces of genes from the south have also largely disappeared from Scandinavian DNA, mostly in Danes. Why?

- The Vikings' trading and plundering journeys to the west were above all targeted to Great Britain and Ireland. Genes from here left far more lasting evidence, especially in Norwegians' DNA, but also in Danes and Swedes.

- Nevertheless, all in all, much of the genetic material that flowed into Scandinavia during the Viking Age has since disappeared.

- The DNA component that has left the most lasting evidence in the genes of Scandinavians came from the north-east. More about this further down in the article.

Were they slaves?

Were the people who were brought from the east during the Viking Age slaves who didn’t have children with Scandinavians? Is that why there is so little genetic evidence of them?

“They may have belonged to groups that were not allowed to form a family or have children,” Anders Götherström said to the Swedish journal Forskning&Framsteg.

Götherström is a professor of evolutionary genetics at Stockholm University and one of the researchers behind the study.

“But they also could have belonged to other classes of people,” he said. “These people may also have been merchants or diplomats or their wives. They may also have been priests and monks who lived in celibacy.”

Don't know how many there were

The researchers have no idea how many people from the British Isles or from areas in the east, south or north settled in today's Norway, Sweden and Denmark during the Viking Age.

What they can read from the human DNA from around a thousand years ago is that the gene flow from the east seems to have been dominated by women.

The researchers didn’t find a similar predominance of people from one sex in people who came from the west.

Specific individuals among the 297 people from the past clearly stand out. A woman who at the end of the Viking Age was given a prestigious boat burial in Sala in central Sweden was completely British.

Before the Viking Age, Scandinavian genes contained only a small element from other places in Europe. One interesting exception is a young woman from the 4th century found in Denmark. She was of British-Irish descent.

A study in Trondheim

Strangely enough, the researchers saw that the fraction of genes from other peoples outside of Scandinavia decreased again in Scandinavians after the Viking Age.

The people who came from other places and their descendants must have had fewer children and fewer descendants than the original population.

In another study from 2022, researchers studied the genes of residents who lived in Trondheim before the plague hit the city in 1347. These residents were compared to Trondheimers from the 17th to 19th centuries. They were also compared to Trondheim residents from our own time.

Here, the researchers found something similar.

The British-Irish genetic component in people in Trondheim during the Viking Age disappeared after the Black Death. You can read more about the Trondheim study in this article from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

In Sweden, people from the east in particular left genetic traces on Gotland and in central Sweden. These genetic traces have also increasingly disappeared up to the present day.

A total of 54 people from Norway

In the DNA that the researchers in the Icelandic-Swedish study examined, 249 analyses were from individuals that had been examined previously.

A total of 54 of these DNA analyses are from people found in Norway – 16 in northern Norway, 24 in central Norway and 14 in southern Norway.

A majority of the Norwegian people were also from the Viking Age.

The researchers behind this new study have themselves analysed the DNA from an additional 48 people, including DNA from the remains of seven people who were victims of a massacre on the Swedish island of Øland towards the end of the 5th century.

The researchers have also examined the DNA of twelve people who were on board the Swedish warship ‘Kronan’, which was sunk in the Baltic Sea in 1676.

Genes from the north-east a thousand years ago

The researchers have particularly focused on the DNA of people in northern Sweden and northern Norway.

This is how they saw that a new genetic element arrived from the north-east and began to spread about a thousand years ago.

The Icelandic researcher Agnar Helgason compared samples from past people in Northern Scandinavia with DNA from today's Finns and Sami. He also made comparisons with the DNA of Native Americans and Central Asians.

In all these peoples he found a common Uralic component in the genes, a DNA feature that is particularly common among Sami and Finns today.

The Uralic gene component

Researchers are only aware of a single find in Scandinavia from the Viking Age where people have this Uralic component. It was found with a family buried in northern Norway.

Based on the limited number of DNA samples the researchers have from before the Viking Age — a total of 25 people — it’s not possible to determine whether this Uralic component was also present to any particular extent in Scandinavians before the Viking Age.

In the 14th century, the Uralic component had spread south into Scandinavia.

The researchers found this Uralic component again in the four men in the crew on board the Swedish warship "Kronan", which sank in 1676. Were these men recruited as crew from northern Sweden or perhaps from Finland?

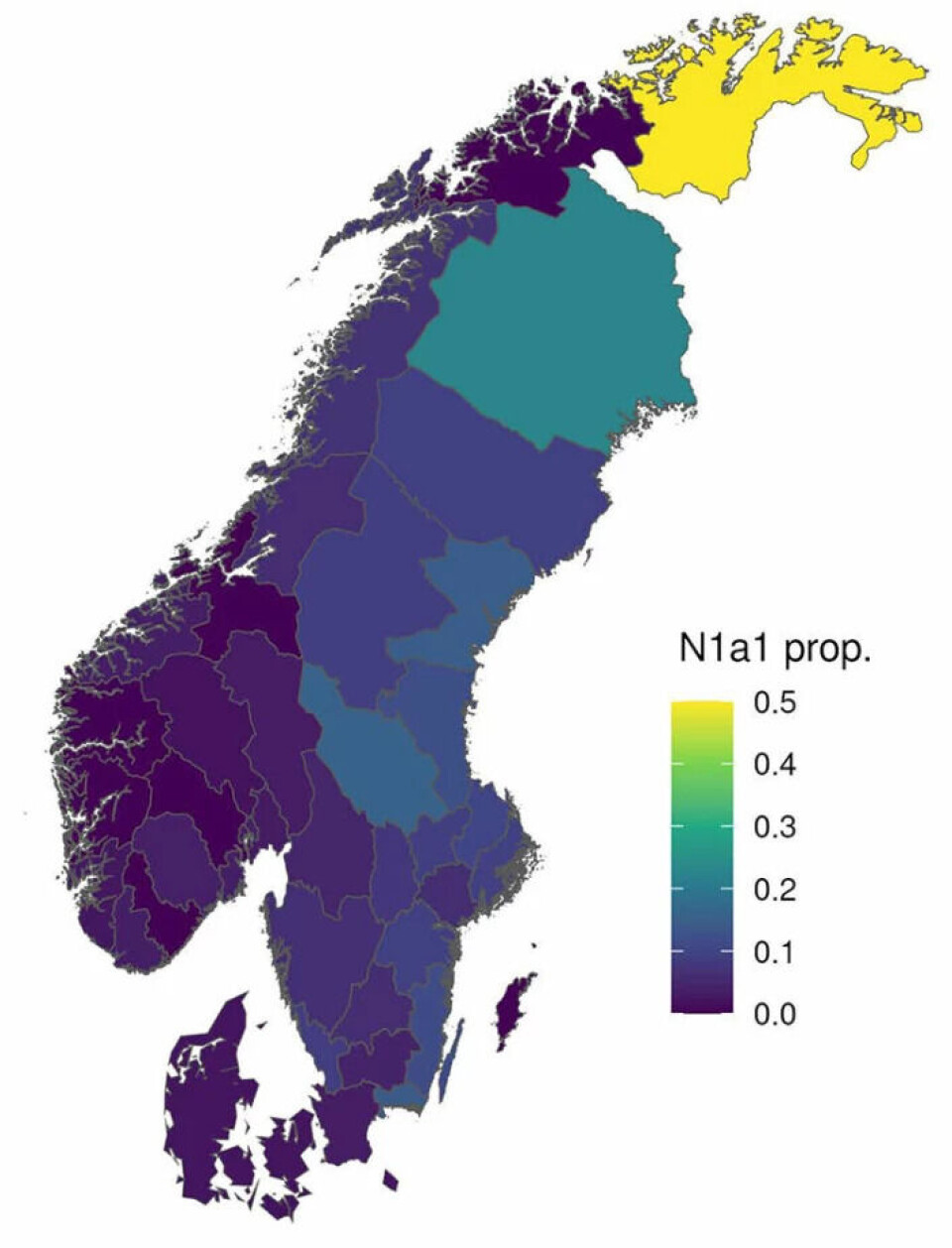

Today, the Uralic gene component that came from the north-east is found in the genes of far more northerners than in just people with Sami or Finnish identity.

In Norway, this gene component is clearly strongest in people from Finnmark in the north.

It is weakest in people in Sogn og Fjordane and in Rogaland, areas on Norway’s southwestern coast.

These genes are even more widespread in much of Sweden than in northern Norway, except in Finnmark.

Possible sources of error

There are several possible sources of error in genetic studies such as this.

A possible source of error lies in the fact that the number of people from long ago who have had all their genes (their entire genome) examined — who have undergone whole-genome sequencing — remains small.

Another possible source of error lies in the fact that excavations and finds of people from the Viking Age are primarily linked to the cities and towns of that time.

The people in these areas certainly had more contact with strangers than other, less urban, people had at the time. Researchers have thus not been able to analyse the genes from a completely random selection of people from the Viking Age.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

Forskning & Framsteg (Research&Progress): "Invandring under vikingatiden satte spår i dna” (Immigration during the Viking Age left traces in DNA), 5 January 2023.

Ricardo Rodríguez-Varela, Anders Götherström et.al.: The genetic history of Scandinavia from the Roman Iron Age to the present. Cell, 2022.

Shyam Gopalakrishnan et.al.: The population genomic legacy of the second plague pandemic. Cell, 2022.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------