Did this Viking helmet belong to a Norwegian warrior who served rulers in the East?

New interpretations of the so-called Gjermundbu find suggest that the Viking buried in one of Norway's richest male warrior graves had ties to great rulers in Eastern Europe.

The Gjermundbu find is famous.

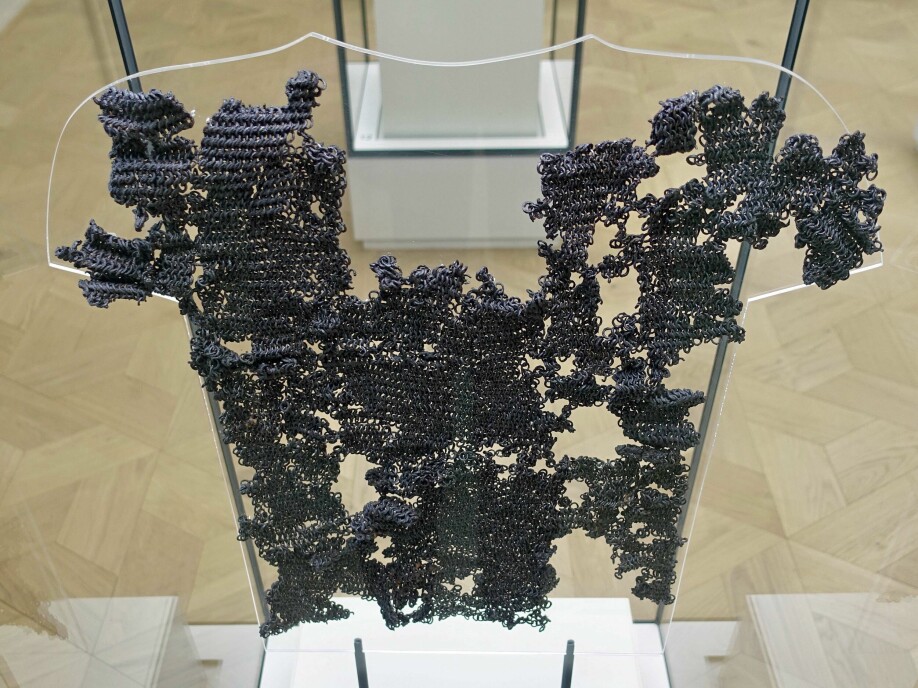

That helmet in the photo, as well as a chain mail that were both found in a mound at the farm Gjermundbu in Eastern Norway are rare objects within Viking archaeology.

Found in nine fragments in 1943, the helmet was subsequently restored. In their presentation of the helmet on their website, the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo refer to it as “The world’s only Viking helmet”.

The museum is however aware that a helmet found in the UK in the 1950s was recently established to have been from the Viking age, making it the second nearly complete Viking helmet in the world.

The Gjermundbu finds, however, have so much more to offer, according to archaeologist Frans-Arne H. Stylegar. Together with colleague Ragnar Løken Børsheim he has re-examined, re-interpreted and attempted to reconstruct the conditions for the find. The two have gone through all the original documentation, as well as newspaper articles and correspondence concerning the discovery, and searched for examples of similar objects and burial styles.

Their findings, which were recently published in the journal Viking, suggest that the helmet might not be so unique after all, at least not if we look East.

More helmets in Ukraine and Russia

Part of the reason for why the helmet and chain mail have been given so much attention, is that this find is unique in Scandinavia and Western-Europe, Stylegar writes.

However, when people claim that this is Europe’s only Viking helmet, they fail to take into account the Eastern parts of Europe.

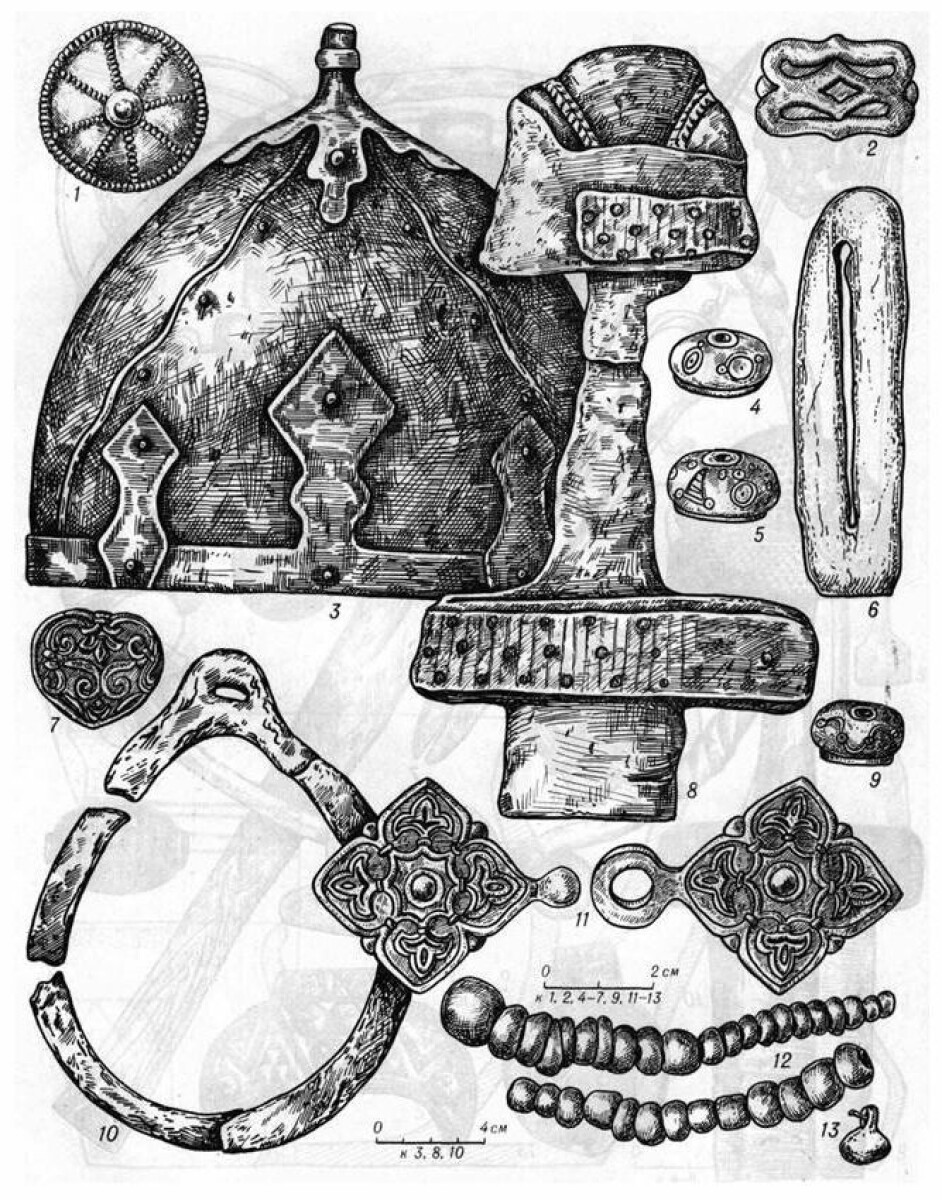

“Further East, in Kievan Rus, helmets and chain mails are characteristic items – if few in numbers – of rich male graves from the 900s,” Stylegar writes in a popular science article about the findings published on forskersonen.no (link in Norwegian).

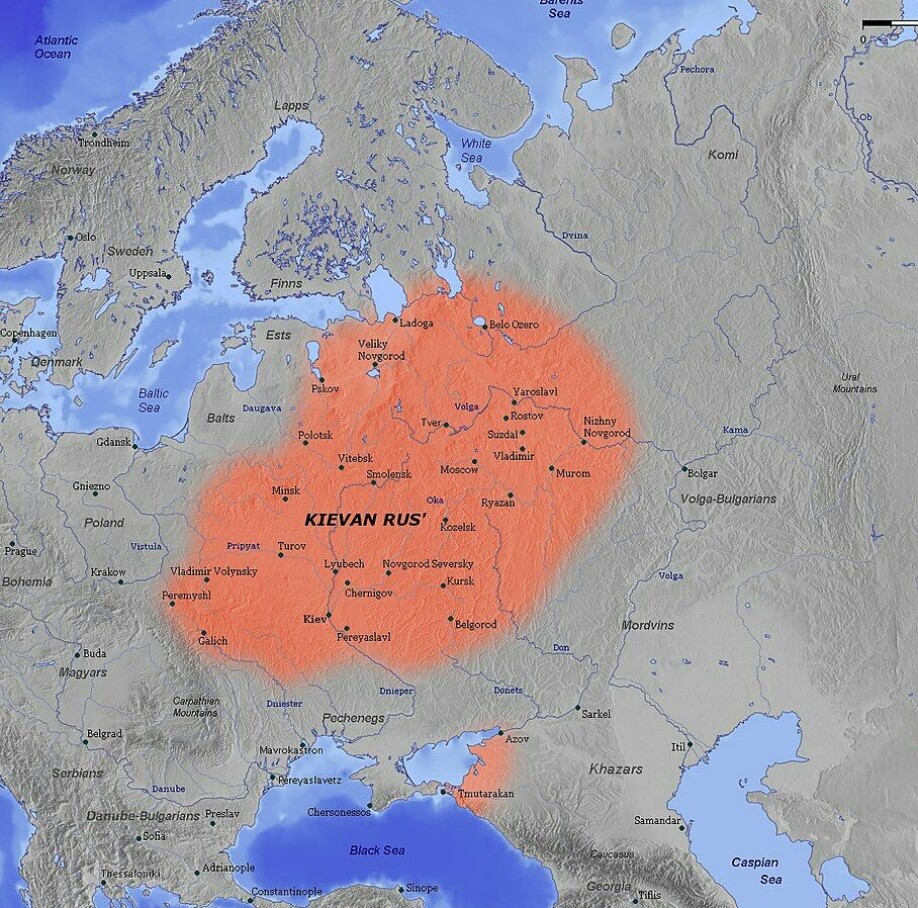

Kievan Rus, known as Gardarike in the Norse sagas, was according to legend founded by Scandinavian Vikings in the 800s. At the height of its existence, the kingdom consisted of large parts of present-day Ukraine and large parts of Western Russia.

“The graves where helmets and chain mails sometimes occur, are found in Russia and Ukraine,” Stylegar writes on forskersonen.no.

These are gravesites that are connected to the rulers of Kievan Rus and their closest companions, also known as druzhina. According to Stylegar, examples exist in graves from Gnezdovo near Smolensk and Jaroslavl, both in Russia, and in Chernihiv in Ukraine as well as in Ukraine’s capital Kiev.

In the mound of Chernaya Mogila in Chernihiv, two helmets and fragments of one or two chain mails were found in the remains from the funeral pyre, among other things.

The helmets in alle these graves are of different types than the one from Gjermundbu, but the idea of including them as grave goods is similar, Stylegar points out in an email to sciencenorway.no

Discovered by chance and hidden in a barn

Needless to say, excavating a Viking grave during wartime – Norway was under Nazi occupation from 1940 until the end of the second world war in 1945 – was no easy feat.

“With travel and other restrictions in place, a full-scale rescue excavation was not possible,” Stylegar and Børsheim write.

The discovery itself happened by chance, when farmer Lars Gjermundbo decided to remove a mound from his land. When Lars had to go undercover in the woods to hide from the Nazis, his son Gunnar found the treasure. He loaded it onto a wheelbarrow and hid it in the barn so the Germans wouldn’t get a hold of it.

Consequently, the find is poorly documented. It has since been overshadowed by the magnificent and famous helmet and chain mail and has according to Stylegar and Børsheim barely been examined and analyzed in its entirety since it was first presented by archaeologist Sigurd Grieg in 1947.

Another reason for why the find in its entirety has not had a huge impact on Norwegian Viking Age research is, according to Stylegar, that the Norwegian focus for many years after the war was on the Viking’s contact with the British Isles and other western connections.

One of the richest Viking graves

“What is certain, is that we are dealing with a very rich grave from the end of the 10th century, with few if any parallels outside the milieu of the large ship graves,” the archaeologists state in the scientific article.

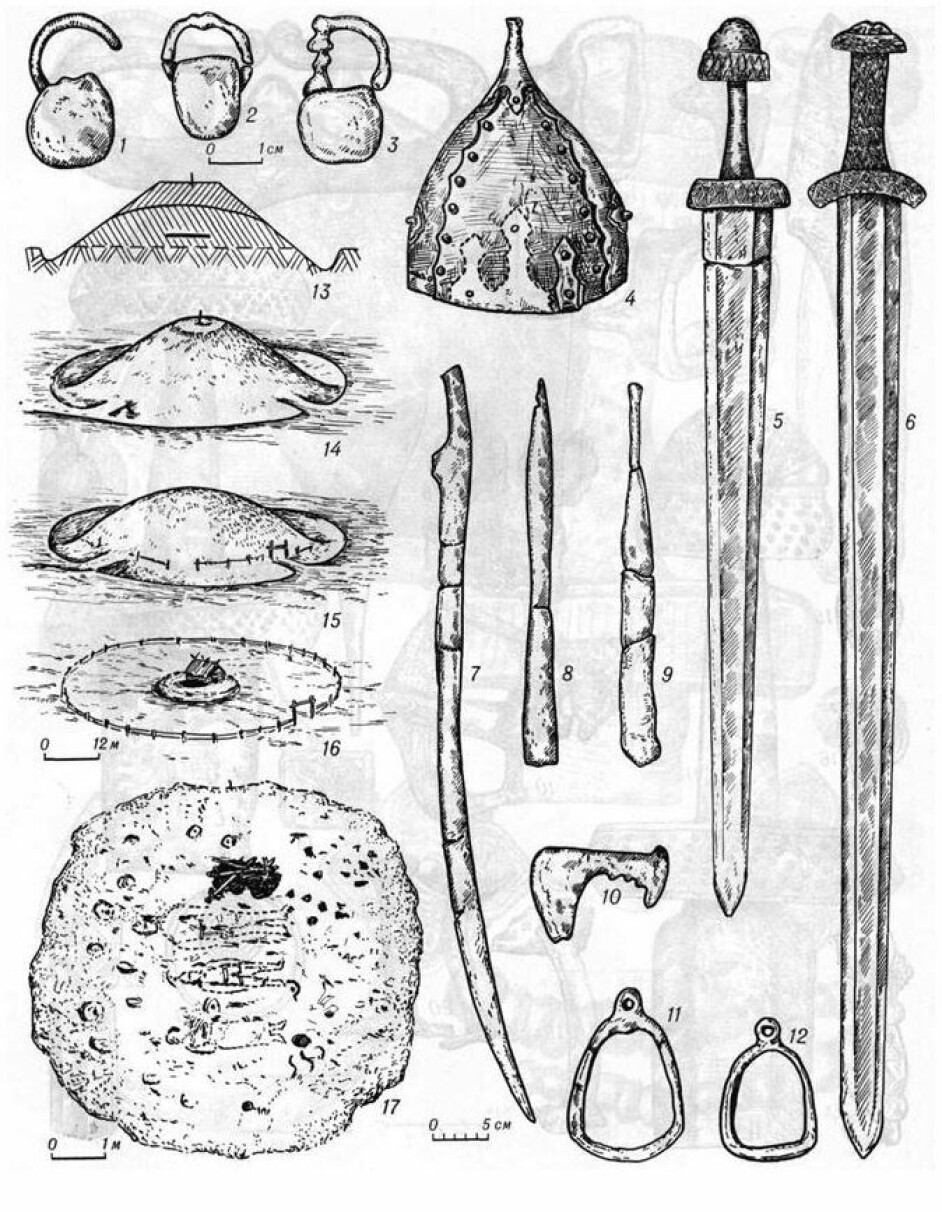

The large mound that covered the grave contained several items besides the helmet and chain mail: Two swords and a large knife weapon, two axes, two spears, four shields and arrows, dice and game pieces, equipment for at least five horses, one or maybe two sledges, several chests and caskets as well as various tools.

Stylegar writes on forskersonen.no that the items are unusually well made, particularly a magnificent sword, and one of the spearheads. The helmet and the chain mail, he writes, are unique.

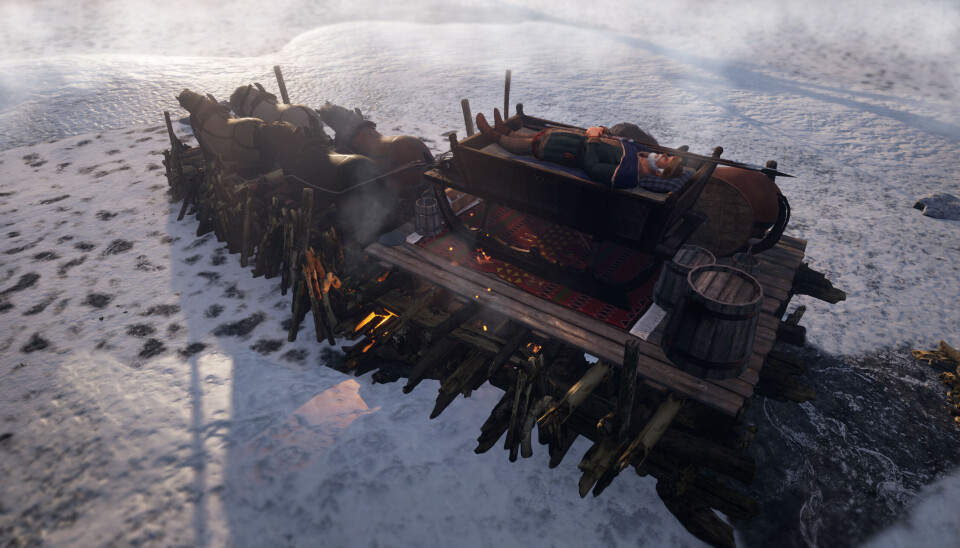

The grave is a cremation grave. The custom at the time would have been to leave the remains of the funeral pyre, ashes, burnt bones and gifts for the grave as they were and then cover them. In the Gjermundbu grave, however, most of the items were placed under a large iron kettle. This was placed under the layer that may be the remains of a funeral pyre.

The archaeologist Grieg believed that this must have meant that the mound contained two different graves. Stylegar comments that this may be, but if so, then both burials took place toward the end of the 900s. He also believes that what has traditionally been interpreted as different graves in the same mound may in fact be traces of the same burial but different ways of carrying out the ritual.

A burial with clear Eastern characteristics

The sledge or sledges found in Gjermundbu also have parallels further East, Stylegar writes on forskersonen.no.

They were known in Eastern Norway, and partly also in Eastern Sweden – but written sources also tell of the central role of sledges in burial rituals from Kievan Rus.

The Gjermundbu find is extraordinary, according to the archaeologist. It represents an expression of traditions that point to continuity in former ways of manifesting power, at the same time as it displays connections to the more international phenomena of richly equipped equestrian warrior graves that are found all over Europe in areas where the Christian ways of laying people to rest were not yet dominant.

“In our case, this mix displays clear Eastern characteristics,” he writes.

“Certain features of the burial, such as the helmet, the chain mail and the sledge, suggest that those who organized this funeral may have themselves experienced how rulers in the East were buried.”

A Norwegian Viking warrior who went East

So who was he, this great horseriding warrior, buried at Gjermundbu some time at the end of the 10th century? We will never know for sure, but Stylegar has some theories. The Eastern characteristics of the burial must have come from somewhere, he writes. Stylegar believes he may have been a Norwegian Viking warrior who participated in the druzinha of the ruler of Kievan Rus.

“It was not unusual for Scandinavian warriors to join the armed guards of famous rulers at the time,” he writes.

“Written and archaeological sources talk about men who went to England or the distant Byzantium, while others went to the princes in Kiev or Novgorod.”

And it is in the part of Norway where the Gjermundbu farm is found that we find the clearest traces of Norwegian Vikings who went into service of the Kievan Rus’ Princes. The runic inscription of the Alstad stone at Toten for instance, remembers a person who died in Kievan Rus. Several other Norwegian warriors are known to have had positions in Kievan Rus under Vladimir the Great.

“The heavy horseriding equipment that we find at Gjermundbu, combined with the helmet, chain mail, bow and arrows and several swords, are like an echo of the Kiev Prince’s battles against various horse mounted nomads on the steppes in the South and the East,” Stylegar writes.

“The person buried at Gjermundbu must have been a part of the tradition of travelling East. It is not unlikely that he had a leading role in this matter, perhaps he even organized it,” he suggests.

More research on Eastern connections to come

“It is of course interesting if the Eastern connection suggested here turns out to be correct, but it’s not necessarily sensational,” Christian Løchsen Rødsrud says to sciencenorway.no.

Archaeologist Løchsen Rødsrud is the project manager of the Gjellestad Viking ship dig.

“This find has in itself captured the imagination of most archaeologists since it was discovered during the war, so this new piece of work by Stylegar and Børsheim is welcome, and it brings the research in this area one step further,” he says.

“Perhaps it will inspire thought processes in other researchers, that may be able to activate other finds that point to Eastern connections.”

Løchsen Rødsrud confirms that archaeologists in Scandinavia have had blind spots when it comes to looking East.

“There has been a lot of focus on Western Europe, both due to availability and connections between researchers, but also due to language barriers,” he says.

“There has been some change in this matter in recent years, and I believe that we will be seeing interesting research on Eastern Viking connections in the future.”

No DNA in a cremation grave

It could be that the Gjermundbu-Viking originally was from the area where he was buried, and that he went East and had a career in the Kievan Prince’s druzinha or another eastern leaders’ retinue, Løchsen Rødsrud says. Or perhaps he went on a trade and/or plundering mission in the East and brought back these objects.

More speculatively he could have originally been from the East and brought the weapons and artifacts with him to Norway. Establishing this origin for sure may be difficult.

“To be absolutely sure we would need to do a DNA-analysis or find items with organic material that could be used for isotopic analysis to trace an origin,” Løchsen Rødsrud says.

But the grave in question was a cremation grave, making these kinds of examinations largely impossible.

In the future, according to Løchsen Rødsrud, the technology for establishing the origins of iron will become so good that it would be able to say something about the origins of the items in the grave. The method, however, is destructive to parts of the objects which are analyzed, and so must be carefully considered before using it on such unique material.

Unique among Scandinavian Viking age weapon graves

Vegard Vike works on conservation of archaeological objects at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo. He specializes in weapons and tools from the Viking age and has among other things worked on both the Gjermundbu helmet and chain mail.

“The theory that this burial is influenced by eastern tradition is definitely interesting as an explanation for the presence of the helmet and chain mail in the Gjermundbu grave, which is almost unique among the many thousands of Scandinavian weapon graves from the Viking age,” Vike writes in an email to sciencenorway.no.

Except for the sword chape, the other finds from the grave are, however, not distinctly eastern, he holds.

“I wouldn’t call the sword chape distinctly eastern necessarily, but scabbard chapes such as the one found here are not as common in Norway as they are further East, for instance in Sweden, the Baltics, Russia, Ukraine and so on. We have found as many as around 3000 Viking age swords in Norway – but only around ten such scabbard chapes for swords,” Vike says.

He also mentions, as does Stylegar, that the helmets found in eastern graves are of a different make than the one found in Gjermundbu.

“But this doesn’t disprove the theory,” he says, adding that the grave certainly was a very rich equestrian warrior grave.

The type of armour found in the grave, such as the chain mail, was reserved for professional warriors and other elites during the Viking age.

“We also assume that there were sledges in the grave, which were burned, but the remains of these are not certain,” Vike says.

“A good story is spiced up by assumptions,” he concludes.