Butchery law with anti-Semitic roots

The kosher method of butchery, called shechita, was fiercely debated in Norway and the rest of Europe before WWII, often with anti-Semitic undertones. Norway is one of three European countries that still forbids the practice.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

A debate regarding ritual slaughtering methods began in Norway around 1890. Members of the newly founded animal rights association Dyrebeskyttelsen criticised Norwegian agricultural practices because of inhumane treatment and slaughter of livestock.

They wanted to see new routines implemented to minimise the fear and agony experienced by animals.

Within roughly 20 years the group’s work started to show results. New technology and rising consciousness about animal welfare promoted use of more humane practices on farms and in slaughterhouses. That done, the growing animal protection movement turned its eyes on the Jewish form of kosher ritual slaughter, called shechita.

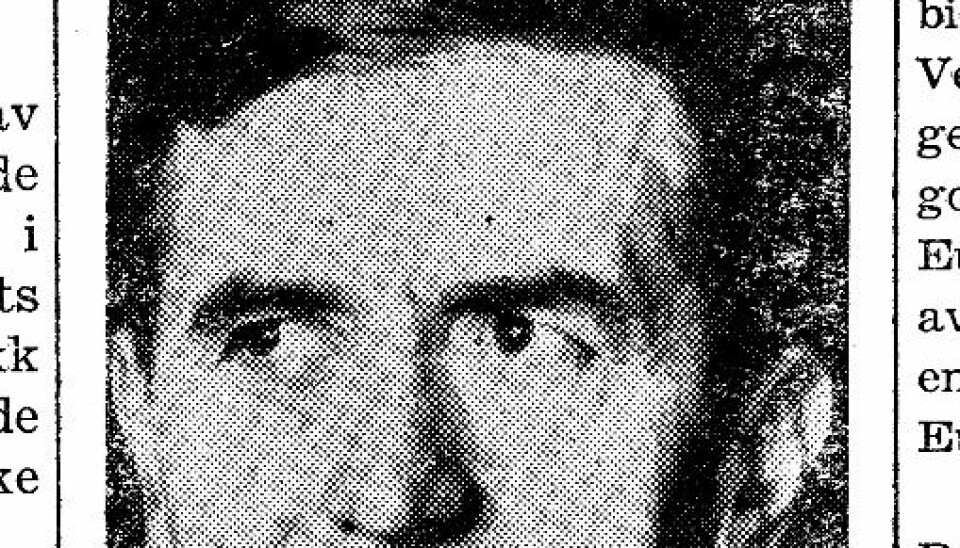

Andreas Snildal, a PhD student at the University of Oslo, is working on a thesis about a public debate which in Norway was called the schächtningsaken – the shechita issue.

He has studied and analysed reams of archival material and followed the debate over ritual slaughter from the late 1800s until a butchering law was enacted in 1929.

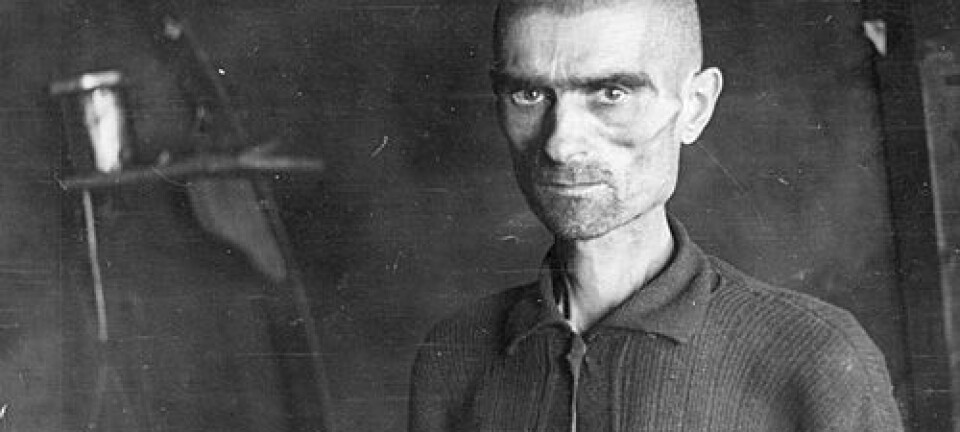

According to Snildal, the content of the arguments remained about the same over the decades, but the rhetoric used started to take on an anti-Semitic character. The welfare of the animals was the focus, but some individuals became preoccupied with the kosher method of butchering animals, referring to Jews as immoral and as people who glorified violence.

Complex background

Snildal says that shechita has complex religious roots. This Jewish method of slaughter is not mentioned in the Torah, but rather in various rabbinic texts or edicts dealing with Judaism’s traditional oral laws.

Shechita calls for an animal’s throat to be quickly slit, ideally severing the oesophagus and several arteries, veins and nerves in a single motion. A sharp, clean, long knife must be used.

This is to ensure that the animal loses consciousness after a few seconds and dies immediately afterwards.

In accordance with kosher tradition, any animal that is to be slaughtered must be free of injury or disease. Jews who keep kosher interpret this to prohibit the stunning or anaesthetising of the animal prior to slaughter. This is what stirred up resistance to shechita and gave it a reputation of being inhumane.

Support from veterinarians

While the debate raged, veterinarians were the most supportive group in defending the Jews’ rights to use their traditional method of slaughter. While confirming that shechita caused the animals some additional pain and prolonged their deaths, they didn’t think it crossed ethical lines. They also felt that respect for religious dogma should be a consideration.

“Veterinarians, in other words the professionals in this field, defended the method of slaughter on a religious basis. So they stepped outside their professional roles. This wasn’t uncommon among experts and public officials of the day. They didn’t only make pronouncements as professionals in their field, but also expressed judgements from general viewpoints,” says Snildal.

Norway, Sweden and Switzerland

Snildal has also looked into the differences in ways the shechita issue was tackled in Norway as compared to comparable controversies elsewhere in Europe. The shechita debate raged in many countries in the first half of the 20th century and bans were passed in Norway, Germany, Sweden and other countries. But the only European countries which still ban the practice are Norway, Sweden and Switzerland.

Switzerland had a more explicitly ideological anti-Semitic movement, especially in German-speaking regions. This movement managed to mobilise a rather large share of the population. After a referendum passed in 1893, the ritual kosher slaughter was banned, against the will of the government.

Swiss Jews who believe in the shechita mandates have had to import kosher meat from neighbouring countries. Jews in Norway imported kosher meat from Sweden until the Swedes enacted a ban on the ritual slaughter in 1937.

New legislation

A new Norwegian law regulating the slaughter of animals was passed in the national assembly in 1929 by a solid majority. This has now been superceded by the Animal Welfare Act, but the content on one point is nearly identical.

Animals that are owned or in any way kept by people must be stunned before being killed. The stunning method must ensure loss of consciousness which lasts from when the killing starts until death occurs.

This provision is incompatible with shechita.

The legal text has not changed much since 1929. It has never contained any explicit reference to Jews or to religious ritual slaughter. But Snildal thinks that the issue must be seen in the context of the public debate that preceded it.

“The law derived directly from the wish to ban shechita. Norway’s first Animal Welfare Act was taking form in 1929 and was enacted in 1935. The law regulating the slaughter of animals could easily have been incorporated in the act, but it was given priority because of pressure to pass a ban,” says Snildal.

Those who exerted the most pressure were Norway’s anti-Semites.

----------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling