Soviet prisoners of war in Second World War – nameless, until now

More than 13,700 prisoners of war from the Soviet Union died in Norway during the Second World War. Only a few were identified in the post-war years, but now names and graves are being matched.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

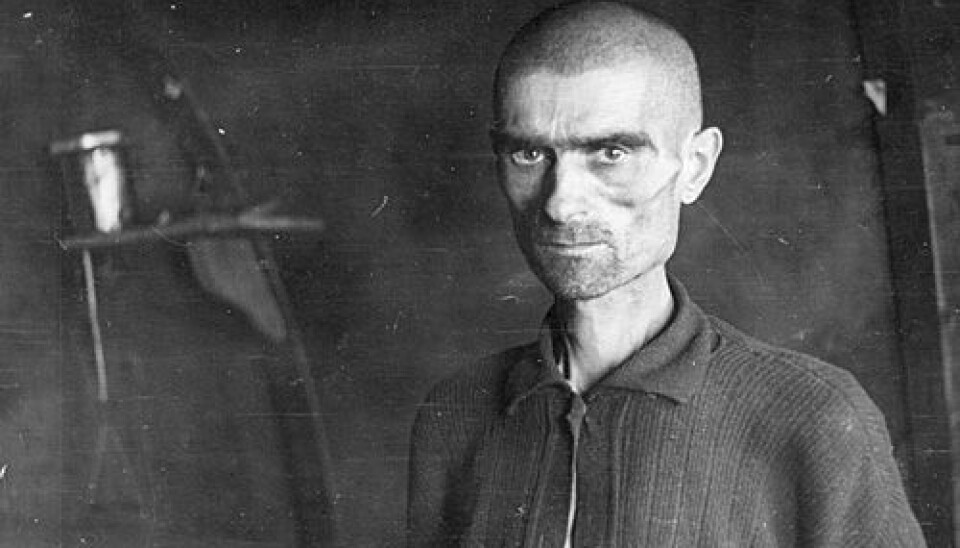

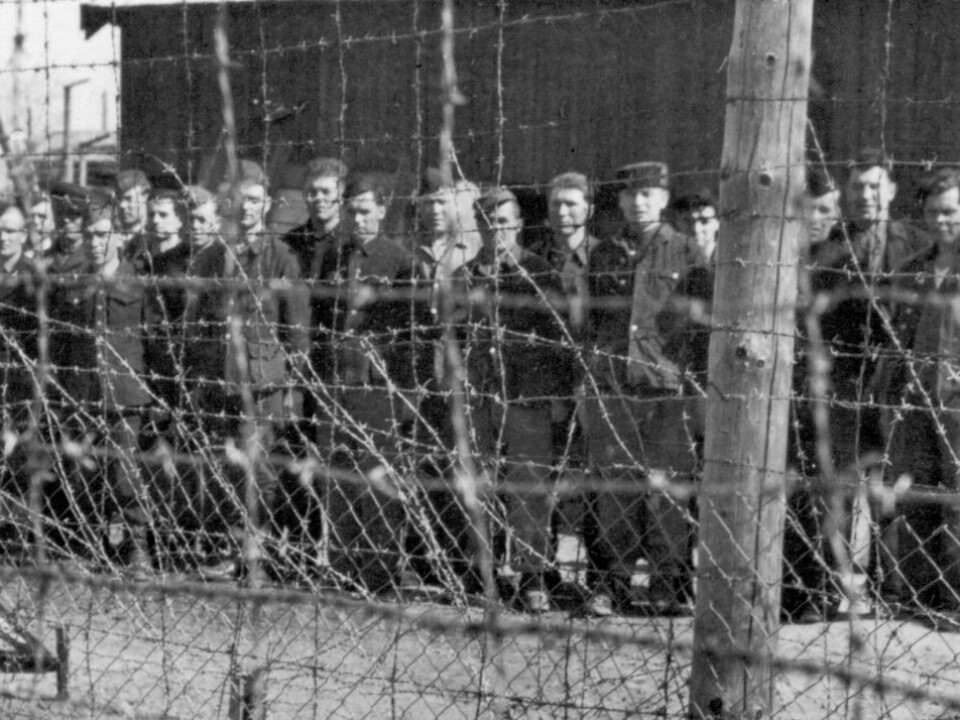

Germany attacked and occupied Norway in 1940, and invaded the Soviet Union the following year. Between 1941 and 1945 at least 98,000 Red Army soldiers were captured and sent to prison camps in Norway. These prisoners of war (POWs) were treated poorly and the Germans ignored several provisions of the Geneva Convention, particularly those regarding accommodation, diet and medical care.

“The conditions were terrible,” German historian Reinhard Otto tells ScienceNordic. “The Soviet POWs were seen as ‘untermensch’ (sub-human) by the Germans, and they were treated much worse than POWs from Western European countries.”

He says many Soviet POWs were placed in Northern Norway, where the German army feared an invasion and where their labor was needed the most. Prisoners were housed in poorly isolated barracks which offered little protection from wind, rain, and the winter season’s freezing temperatures, and these conditions made it virtually impossible to rest and recover from a long day’s strenuous labor.

Constant humidity in the buildings also promoted illnesses such as tuberculosis and pneumonia, which at the time were two of the most common causes of death.

Life for the Soviet POWs was further exacerbated by the poor food rations. The prisoners didn’t get the energy they needed to carry out the backbreaking work, and many of them were eventually tiered out.

Badly treated, but carefully counted

The mortality rate for the Soviet prisoners of war was high. According to The Falstad Centre, a Norwegian memorial and human rights centre, they were in fact the largest group of war casualties in Norway.

The total number of Norwegian war casualties is estimated at 10,262, significantly less than the 13,700 Soviet prisoners of war who lost their lives.

Reinhard Otto’s research shows that the German army did a very good job at keeping track of their Soviet prisoners – they were counted and identified, and if they died during captivity the official cause of death was often noted on the prisoner’s identity card. The card also contained the prisoner’s name and a specific number which linked them to their prison camp.

The identity cards were initially sent to archives in Berlin. When the war ended the records were confiscated by the Red Army, who brought them home to the Union. Here they gathered dust for decades, until the project ‘Soviet and German prisoners of war and internees’ was initiated and Germany and Russia began to share information about POWs and their burial sites.

The identity of deceased Soviet POWs and their whereabouts in Norwegian cemeteries were in other words not missing due to poor administrative work by the German army, as first thought, but rather because little was done in the post-war years.

No visitors

If deceased Soviet POWs and their burial sites in Norway were identified, many Soviets probably would’ve liked to visit these to pay respect to their fallen family members. But, in the age of the cold war with mutual mistrust between the capitalist west and communist east, neither Norway nor the Soviet Union wished for tourism across the Iron Curtain.

Reinhard Otto argues that Norway wanted to avoid Soviets visitors as they feared being infiltrated by spies, particularly in Northern Norway, an area NATO saw as a strategically important in case of a hot war. The Soviet Union, meanwhile, wanted to save their communist citizens from exposure to the alternate lifestyle in the capitalist west.

Naming graves is a responsibility

Reinhard Otto says it’s the responsibility of Germany, Norway and Russia to ensure that the families of the fallen POWs have graves to visit.

“It’s obviously easier to travel from the east to the west today, and many grandchildren want to visit their grandfathers’ graves,” says Otto. “And now that we are able to match graves and names we should do so.”

The Norwegian historian Michael Stokke has researched Soviet POWs in Norway for the past 13 years. He agrees with his German colleague, and he tells ScienceNordic that he has personally felt the need for this kind of information.

“We’ve been contacted by about 20 Russians who want to visit the graves of their fathers and grandfathers,” says Stokke.

“We were contacted by someone who thought their grandfather died in Ukraine, until they found out he was in fact buried in a cemetery in the outskirts of Bergen. They came over here and covered the grave with soil they’d brought from home.”

He says it was a powerful moment.

“It was a great relief for them, I think, to finally know where he was buried,” says Stokke.

Many names to go

Norwegian authorities contacted Reinhard Otto in 2008 as soon as they became aware of his work and learned that it was possible to identify most of the Soviet POWs who died in Norway.

In 2012, the work is still on-going. While Otto has returned to Germany, Norwegian researchers are still working on matching names and graves. About 8,000 of the 13,700 who died in Norway have been identified so far.

“I think at least 9,000 can be identified,” says Otto.

--

The Falstad Centre is currently adding names of dead POWs to their searchable archive - in English here. A similar archive which includes information from other countries is found at www.obd-memorial.ru.

Reinhard Otto’s article Cemeteries of Soviet Prisoners of War in Norway was recently published in the Norwegian journal Historisk Tidsskrift.