A name on a war monument

Einar Engedahl is one of 34 names on a memorial stone for a school’s alumni who fell in battle during WWII. His story has now been revealed through collaboration among pupils, a teacher and a researcher.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

A memorial stone stands on the grounds of Stavanger Cathedral school. Carved in granite are the names of 34 former pupils who were killed during World War II.

Today’s pupils rarely notice the monument, except on Norway's Constitution Day, May 17, when flowers are ceremonially placed there.

The late member of the WWII Resistance movement, Inge Steensland, knew many of the young men whose names are on the memorial. He did not want them to be forgotten, so he contacted historians at the University of Stavanger (UiS).

The fallen become a school project

Ole Kallelid, an assistant professor in history at UiS, was responsive and followed up together with his colleagues at the Department of Cultural Studies and Linguistics.

“We decided to contact the teachers at Stavanger Cathedral school. We wanted to make use of the pupils' connection and proximity to the memorial."

Heidi Løge was a history teacher at Stavanger Cathedral school when the request came from the university.

“Our curriculum calls for more research by the pupils themselves, and they are supposed to research a famous person,” says Løge.

“We started a project in history where final-year pupils were each given a name from the memorial and asked to write a biography,” explains Kallelid.

Into the life of a stranger

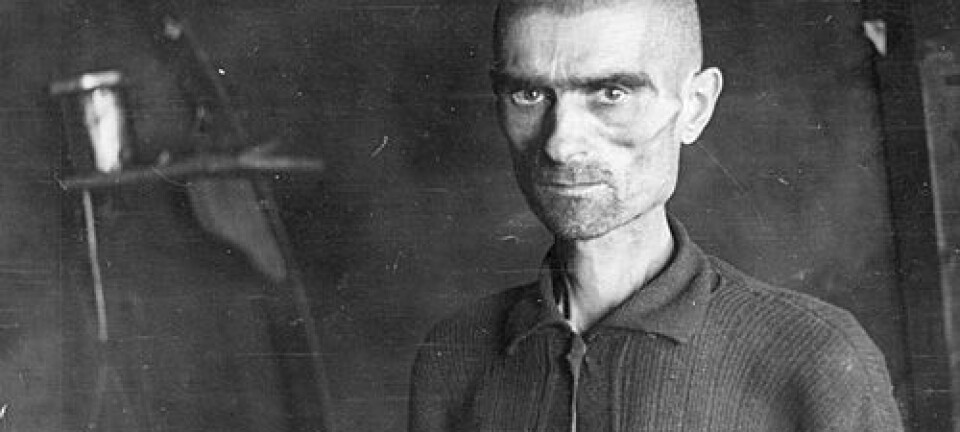

Einar Engedahl is one of the names inscribed on the monument:

In the early hours of 1 May 1944 the Gestapo hammered on his door. Together with his friend Alv Aanestad, he was nabbed and thrown into a car. The Germans were trying to find a cabin where an illegal transmitter was concealed. Einar wound up splayed on a table at Gestapo headquarters being beaten with a club. He claimed ignorance of any such cabin, to no avail.

Hanne Harbo is the pupil who was issued Einar’s name. The assignment was to write his history and tell why he became one of the names on the monument.

“It was really special to enter the life of a person who was a complete stranger," says Harbo. "I kept wanting to learn more about what he was like, what he experienced and how things went for his family."

Hunting for sources

Before the pupils started working on the project, researchers at UiS met with them and held a motivation and information seminar. The pupils were introduced to ethical issues, methods, how to react to taciturnity and selective memories and were given a push toward sources where they could start their searches.

“We were given useful tips from the researchers at the university before we started. We had meetings with them underway and they helped out if we got stuck. It was great that the university showed an interest in work by high-schoolers,” says Harbo, who was 18 at the time.

The pupils were directed toward newspaper archives, church records, literature and censuses, but also encouraged to seek out the families and others who had known the fallen alumni.

“Sometimes it was easy to find family members or old schoolmates, but other times the kids had to walk up and down the streets where the deceased had lived and ask old people whether they had known him,” says researcher Kallelid.

A friend relates

When Harbo started her work she was unable to locate any relatives of Einar Engedahl. But she had the name of his childhood friend, Emmanuel Aarrestad.

“It was wonderful talking to his friend. Aarrestad was 99 years old and the last remaining person who knew Engedahl. He didn’t give me all that many facts, but he described Einar in a way that no other sources could,” explains Harbo.

“The older information sources were surprised and delighted that today’s kids cared. Several of them telephoned around to others, trying to help the pupils,” says teacher Løge.

Youth as researchers

The project was demanding for pupils and their teacher. But Heidi Løge says it was rewarding:

“Here they faced challenges on personal and scholarly levels. The pupils met persons who told their history and got close to primary sources, which they seldom do otherwise. Several of the pupils were told stories that had never been told before," she explains.

The teacher thinks the history project became special because the teenagers entered it from their standpoints.

"They aren’t well-read, professional historians; they are naive and open,” she says.

The historians agree that the project benefited from the use of pupils:

“It might seem less difficult for the informers when a young pupil comes to talk with them. They aren’t as scary as a researcher,” says Ole Kallelid.

But being a teenager does pose some challenges:

“18-year-olds have active lives with school, part-time jobs, sports and exercise, not to mention hanging out at cafés. Some of the pupils had a tendency to postpone working on the project, so they had less time for reflection,” explains the historian.

Einar’s death

In addition to writing a biography of the person listed on the memorial, the pupils were required to write about the methods they used and their reflections on the assignment.

Through her insight into Einar Engedahl’s life, Harbo learned more about major episodes in WWII and how the war shaped modern Norwegian society.

“History suddenly became a completely different subject when I was given the opportunity to do my own digging. I also learned how important it really is to preserve the tales and memories we have from the war,” Harbo wrote in her assignment.

Engedahl was sent to the Natzweiler Concentration Camp in October 1943. According to Harbo’s paper, he had to work 12-14 hours a day at a stone quarry in thin cotton clothing and had to stand out in the cold listening to long propaganda speeches.

On 11 June 1944 Engedahl died at Natzweiler from malnutrition and dysentery, 34 years old.

A teacher’s dream

Engedahl’s life, war contribution and tragic death can now be found on eight closely-written pages, including pictures and sources written by Hanne Harbo. This will be combined with the other papers submitted by her classmates and the contributions of the researchers.

Historians at the university will use the work in a larger project about WWII. And they might have recruited some future colleagues:

“I have no doubts that some of these pupils will become researchers. I received plenty of feedback saying they got a new attitude regarding what the subject of history really is,” says teacher Heidi Løge.

“For me as a teacher the methodology of the project was the most fascinating. Experiencing the pupils’ reflections about the choices they made. How they tackled dead ends before discovering new inroads. It was just the way research work goes. I witnessed an involvement that a teacher can usually only dream of; it was a fantastic feeling!” says Heidi Løge.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling