On the track of the world’s first farmer

The very first farmer may have lived in a barren mountain landscape in Turkey over 10,000 years ago.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

When and where did humankind first start cultivating the soil? The experts haven’t formed a single chorus on that issue, but a very good candidate for the site is found near the Mountain Karacadağ in Anatolia − in southeastern Turkey.

This is where the first humanly modified grain was developed − einkorn [literally: single grain] wheat.

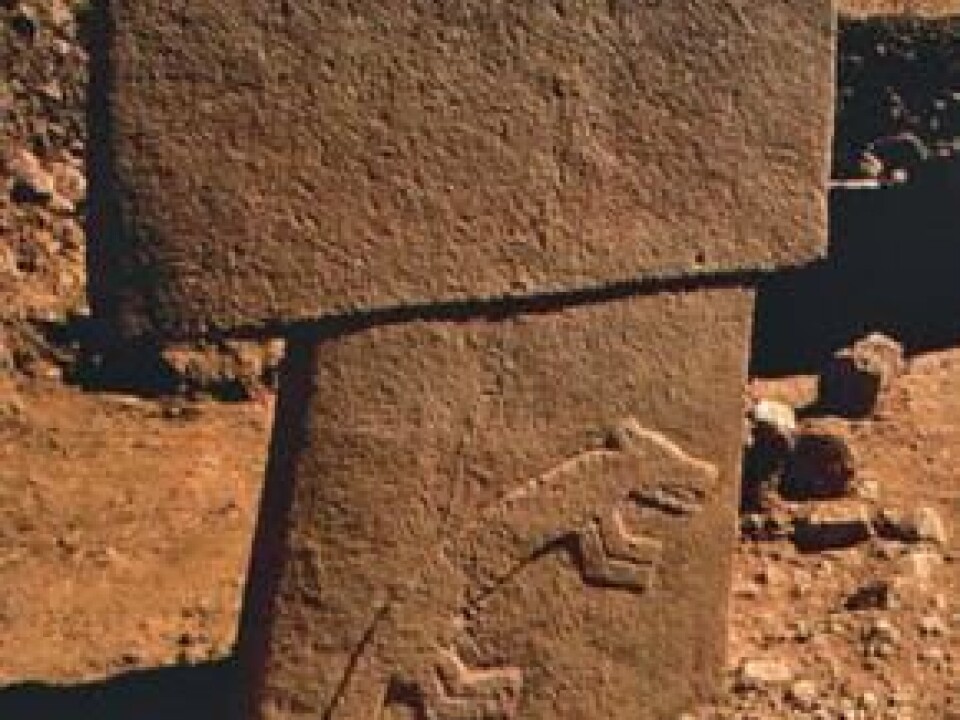

The grain is now being more closely linked to one of archaeology’s major puzzles – the mysterious and ancient site Göbekli Tepe with its limestone megaliths decorated with bas-reliefs of animals. Nobody has been able to satisfactorily interpret their full significance.

Göbkeli Tepe is in southeast Turkey, about 30 km from Karacadağ.

Could hunter-gatherers have been the people who constructed this site 7,000 years before Stonehenge and the Great Pyramids of Egypt, and also become the first people to start cultivating the soil? Plant genetics can help answer that question.

A significant find

Professor Manfred Heun at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB) is an expert on cereals. Along with Italian and Turkish colleagues in 1997 he determined that Karacadağ could be the original home of the cultivated form of einkorn.

He’s returned time and again ever since.

“It feels great being there. This is a mountainous area − Karacadağ has an elevation of over 1,900 metres. But it doesn’t look like a high mountain, it’s more like a Norwegian mountain plateau,” says Heun.

The people who currently dwell in the region are stationary Kurds and Turks as well as nomadic Arabs who making a living off herding sheep, cows and goats.

The primal wheat

Evidence indicates that einkorn is our first cereal. It’s a kind of wheat which is much older than spelt, the grain so many health-conscious people now swear by.

Einkorn was essential for humanity for several millennia but is now only commercially grown a few places in the world.

The cultivated or domesticated variety of einkorn stems from a wild einkorn that still grows in mountain areas of the Middle East.

We say a species of grain has been domesticated when it has undergone changes due to human influence.

Domestication is a key term that unites archaeologists and geneticists who are striving to find the origin of agriculture.

Just as the dog evolved from the wolf, and pigs evolved from boars, our cereals have been significantly altered by human cultivation.

Silent witnesses

These changes can be detected and read in the genes of modern crops as tales linked to the first farmers’ experiments. They are witnesses that speak to us nonverbally.

In addition to einkorn, emmer wheat and barley are two major cereals that were domesticated very early in the Middle East. They share a primitive and natural trait: when mature the grain of the wild varieties falls to the ground so it can be spread with the winds.

Those who wish to harvest these grains either have to tediously pick up the grains one by one after they fall to the ground or cut the stem with a scythe before it ripens.

Mutations

However, in wild populations now and then a natural mutation occurs in individual plants: the straw that supports the cereal doesn’t bend and break when the grain is mature.

If someone is careful to only use these specimens as seed grain they can pass this genetic trait on to new generations of the plant. This is exactly what the first farmers have done.

Other preferable traits were large grains, an evenly distributed ripening period and a reduction of the inedible chaff that protects the seed kernels. Any set of these and other preferable traits tells us that we are dealing with a domesticated variety of cereal.

Archaeologists look for these indications of domestication when they find cereals during excavations of Stone Age settlements in the region.

Like CSI

The task that Heun and his colleagues assigned themselves was to find out where einkorn was originally domesticated. The region where wild einkorn wheat grows is large, covering parts of Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. Wild einkorn is also genetically diverse.

The challenge was to make a genetic match between different varieties of einkorn and today’s domesticated variety. Heun says this is somewhat akin to the work of forensic medical experts on CSI.

The difference is that they weren’t looking for a murderer, but rather a “crime scene” that was 10,000 years old.

Help received from immigrants

The results were achieved after cultivating an einkorn from seed samples and investigating the DNA from no less than 1,362 wild varieties that came from large areas of the Middle East and Europe.

At this point Heun was working at the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research in Cologne and the team hung up a giant map of Turkey and the Middle East with the origins of the enormous number of einkorn varieties marked off.

Many of the cleaners at the institute were immigrants from the region and they enjoyed finding their home birthplaces on the map. They also helped the scientists now and then when they were having trouble figuring out where to pin the grain types to spots on the map.

“They often helped us by locating their towns,” says Heun.

The grain varieties seemed to home in on the area around Karacadağ. This conclusion prevails today even though arguments can be made that einkorn developed at more than one spot; so the debate continues in international research circles.

Three grains of rye

After the einkorn study was published the origin of emmer wheat has also been traced to the same area.

The lab results from geneticists are confirmed by archaeologists, who have found the oldest specimens of domesticated einkorn and emmer wheat from this very area, dated at 10,200 – 10,500 years ago. These can be traces of the earliest cultivation of cereals in the world.

A settlement site at Abu Hureyra in Syria previously gained plenty of attention because of a discovery of a domesticated rye, dated at 12,000 to 13,000 years old. But the archaeological evidence for this site is rather skimpy – just three grains of rye – and in any case there is no proof that a tradition of rye cultivation occurred here.

Might disappear

When Heun visited Karacadağ the first time he found wild einkorn plants. The last time he was there he found none. He thinks overgrazing of sheep could be the problem and fears that precious stocks of wild grains might disappear forever because nomads run their livestock there.

“The nomads are poor – nobody can blame them. But the Turkish State ought to do something to preserve the area,” says the UMB professor.

Karacadağ is near Diyarbakir, which is the largest city in the Kurdish dominated southeastern region of Anatolia in Turkey. It’s close to the borders of Syria and Iraq.

This is also a region where Kurds, Arabs and Turks have been at war. In ancient times the armies of Persia, Constantinople and Rome marched through. This was the core area of the Hettites.

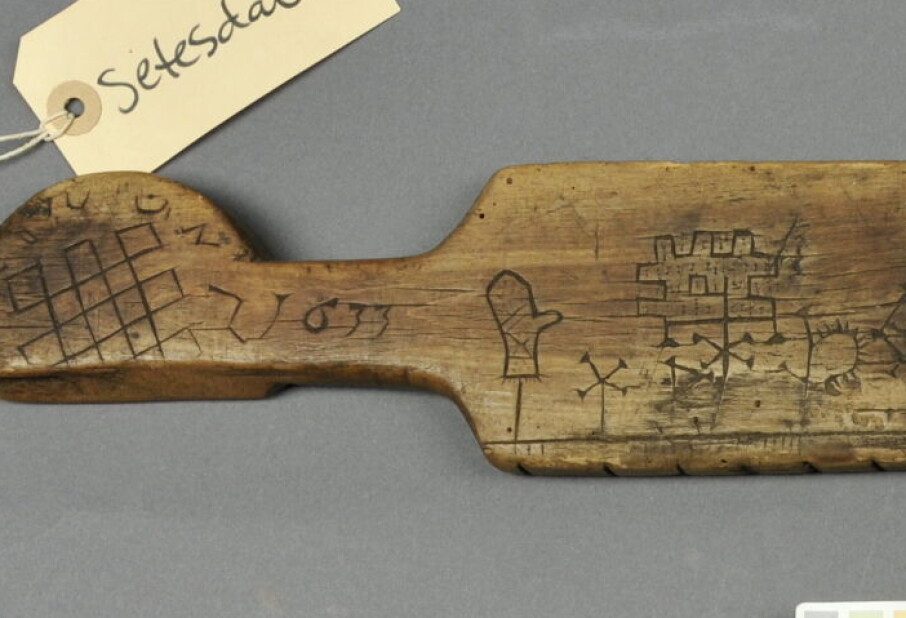

Mystical figures

But the area has a much older history. In 1994 Göbekli Tepe was discovered. Its multi-tonne T-shaped pillars and megaliths decorated with mystical animal figures including, lions, hyenas and spiders are still being excavated from the sands. The oldest finds there are estimated to be 11,000 years old, from the time just prior to the Neolithic Revolution – the start of agriculture.

This baffles the researchers, who cannot explain exactly what kind of place this was. But it’s believed that it was a large religious temple complex in use for hundreds of years, before it for reasons unknown were deliberately buried.

However, new discoveries, which haven’t been published yet, link the cultivation of einkorn at Karacadağ more closely to the puzzling place.

Maybe there is a common denominator between why the stone pillars were built and why the cultivation of einkorn commenced. Perhaps the answer is beer.

Come on over for some beer?

Erecting the Göbekli Tepe megaliths demanded an enormous amount of work. But what do you do if you want to get several hundred people to work together for weeks and months at a time, cutting, carving, dragging and lifting tonnes of rock?

But of course, you offer them beer! Beer would probably have been a prestigious and rare commodity, both nutritious and healthy.

In one of the archaeological layers at Göbekli Tepe, from a period designated as PPNB, tubs have been found that could have been used for making malt and brewing beer.

“Tubs have been found that could have held 150 litres of water. These probably weren’t used for storing grain,” says Heun.

Beer can only be made from grain and to be ensured access to such cereal it’s a good idea to plant a field of it. This could have been a motivation for growing cereals instead of finding them in the wild.

These new findings correspond in time to domesticated grain species. But no discoveries of cultivated grain have been made in the oldest and best known parts of Göbekli Tepe. So hunter-gatherers are still thought to have first built and used the site.

Garden of Eden?

Whatever their initial impulse, the first farmers in the Middle East developed a package of plant species and domesticated animals that had an enormous impact and formed the basis of agriculture in Mesopotamia, Egypt and the Indus Valley in Pakistan.

The gift of agriculture was passed on to the great civilizations in the fertile river valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates, the Nile and the Indus from barren areas of the same region.

The most important plant species were einkorn and emmer wheat, barley, chickpeas (garbanzos), peas and lentils. Tubers were also domesticated just like the cereals.

If one were to search for a single spot where all the wild varieties of all these domesticated plant species grew, the place to go would be just here – in southeastern Turkey and northern Syria. This has been suggested as a region corresponding to the mythical Garden of Eden by the German magazine Der Speigel .

Researchers in the field used to be mainly focused on the settlements in today’s Israel/Palestine. It’s known that this is a region where wild cereals were collected and eaten several thousand years before the first traces of agriculture.

Fastest changes in genetic traits

Now we have a lot more data from excavations further north. We cannot be certain that agriculture in the Middle East originated in just one place. Some propose that people in settlements all over the region tried out local plant species and hence, there were multiple cradles of agriculture in this part of the world.

Some scientists stress that a lot of time would pass from the initial cultivation of wild grains until noticeable genetic changes start turning up.

Manfred Heun disagrees. He points out that einkorn is self-pollinating.

This makes it much easier for new genetic traits to pass from one generation to the next. On the other hand it is less likely to regress back to the initial wild traits than it is for species that are cross-pollinating.

Found edible plants in nature

Heun thinks that 20-30 years of cultivation could have been enough to establish the essential trait of stems that don’t break when the grain is ripe. So the first farmer could have experienced the results of his or her genetic selection efforts in the course of a lifetime.

He thinks that agriculture emerged from the hunter-gatherer cultures’ abilities to find edible plants in nature.

“These people must have developed fantastic observational capabilities and loads of knowledge about wild plants,” says Heun.

History doesn’t always have to involve snail-paced processes demanding hundreds of years.

“I think this happened in one community, in one spot,” says Heun.

If we follow that line of thinking we can thank a single farmer at a particular site 10,000 years ago for agriculture.

Heun is so enamoured with primal grains that he spends some of his leisure time with them and has brewed and bottled what might be the first einkorn beer in Norway since the Bronze Age.

“Einkorn has higher protein content than other grains and is really healthy,” he assures us.

——————————————

Read this article in Norwegian

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

Scientific links

- Melinda A. Zeder: The origins of Agriculture in the Near East, Current Anthropology, vol. 52 in supplement 4, The Origins of Agriculture: New Data, New Ideas, October 2011

- Simicha Lev-Yadun, Avi Gopher and Shahal Abbo: The Cradle of Agriculture, Science 2 June 2000 (Abstract)

- Manfred Heun, Ralf Schäfer-Pregl, Dieter Klawan, Renato Castagna, Monica Accerbi, Basilio Borghi and Francesco Salamini: Site of Einkorn Wheat Domestication Identified by DNA Fingerprinting, Science 14. november 1997. (Abstract)