The crucial choice to cultivate the land

Agriculture gave us cities and pyramids but it can also lead to poorer health. Why did humans choose to go down this road?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

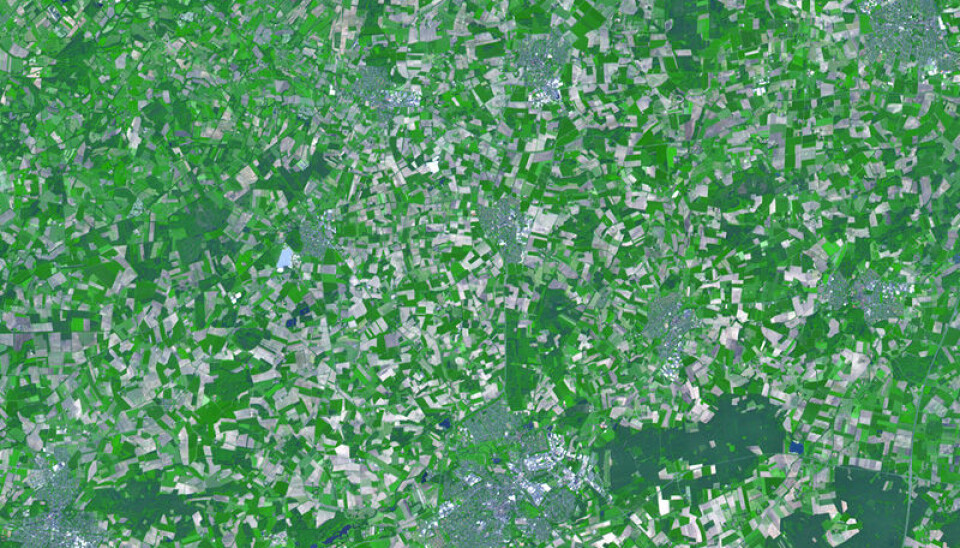

Around 10,000 years ago humans started cultivating the soil. They abandoned the free life as hunters, fishermen and gatherers and started growing cereals in the Middle East, maize in Mexico, rice in Asia and tubers such as cassavas and yams in the tropics.

We tamed wild animals and eventually befriended sheep, pigs, horses, llamas, water buffaloes and camels.

Archaeological studies indicate that the transition to agriculture gave us poorer health and shortened live expectancies. It could also have originated class distinctions and exploitation.

Difficult to understand

Why did our ancient ancestors choose such a life? After decades of debating that question, researchers are further than ever from resolving the issue.

Knut Andreas Bergsvik is an associate professor at the University of Bergen and one of the subjects he has studied is the transition to agriculture in Scandinavia.

Bergsvik says the issue of why people opted for agriculture is a key question but no generally accepted answer has been found.

“New books and studies on this topic are being published constantly. But the reason for the changeover is hard to fathom,” he says.

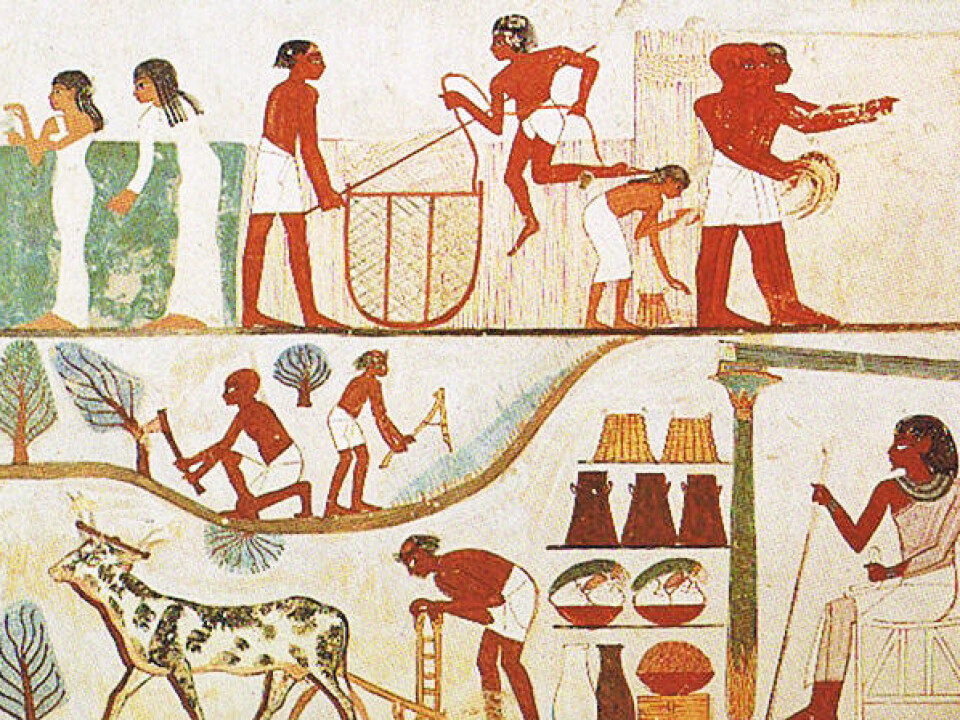

Agriculture was the basis for pyramids and cathedrals

Conceive of a world without cathedrals, pyramids and the Great Wall of China. Without cities, countries, written languages or modern technology. Agriculture was the basis for them all.

If humans hadn’t started cultivating the soil and domesticating animals our entire history would have taken another route.

Researchers are constantly making new discoveries showing that the origin of agriculture has been a global process. People all over the world have participated.

Best known is the cradle of agriculture in the Middle East and the region between the Mediterranean Sea and today’s Iraq, which is called the Fertile Crescent. This is where most species used in European agriculture have their origins.

But agriculture was also developed in China, New Guinea, Africa north of the equator, India, Mexico and South and North America more or less independently of each other in the course of 10,000 years. Agriculture spread from its birthplaces across the continents.

Farming emerged simultaneously

After Homo sapiens had lived as a hunter, fisherman and gatherer for at least 100,000 years, agriculture emerged independently in several regions of the globe.

The concurrence in time for this transition has inspired attempts to find a single global explanation model. It’s been pointed out that the climate following the last Ice Age became more stable and more hospitable to agriculture.

Core samples taken from the Greenland Ice Shelf also indicate a higher CO2 level in the atmosphere, which would have been beneficial for cultivating grain and other plants.

Overpopulation brought change?

Others have asserted that the Earth was simply full. The number of people on the planet had increased during earlier stages of the Stone Age. Ecological niches had been exploited to the maximum and an imbalance between the population and available resources made it necessary in certain areas to find a new way of procuring enough food.

The problem with this explanation is that it hasn’t been backed up by any archaeological discoveries. Perhaps it never will be.

This is because it’s hard for archaeologists to find reliable data for calculating populations in the various areas and determine whether they encountered shortages in wild natural resources.

Beer and meat for allies

Some think the data could point in the opposite direction – that the regions where agriculture was developed had abundant resources. In other words, that agriculture came about in societies that had a surplus, rather than societies that were hard up, and populations were attracted to certain prime aspects of agriculture.

Perhaps cultural and political factors were the key motivation? One possible explanation for the origin of agriculture is that it provided a surplus of food that could be used for partying.

“In hunter-gatherer societies where is everyone is essentially on the same level, more ambitious individuals don’t have that much opportunity to rise above others. A path to status would be to have a sufficient surplus of food to stage large feasts,” says Bergsvik.

Agriculture provides these opportunities because you can raise and fatten a pig or harvest grain and make beer.

Staging parties helps cement alliances and establish dependent relationships.

“It means you can save up food and divvy it out to those you want to have on your side. The main point in such giving is to link people to you. This is a worldwide social phenomenon. In Norwegian we still talk about ‘giving a party’,” says Bergsvik.

The start of social strata

On one hand it’s conceivable that parties – perhaps with a religious connotation – are a continuation of an important theme in hunter-gatherer cultures: Sharing your catch after a successful hunt, fishing trip or forage.

On the other hand feasts were something wholly new, an opportunity to gain status in a society and be what anthropologists call big men. This could have been the start of social strata among humans.

The Middle East is the early agricultural development region that has been investigated the most by archaeologists. Findings from this area support the theory of cultural factors being salient to the transition to agriculture.

Bergsvik thinks that external pressures and the attractive power of agriculture could have both played a role in its emergence.

He points out that identical explanations are not required to clarify why it originated in certain regions and why it was later spread outside these regions.

Detrimental to health

Many believe that agriculture had its costs in the form of declining health. It could have been ill advised to relinquish a permanent low-carb cure consisting of wild game, fish and roots from the forest.

Biologist Iver Mysterud at the University of Oslo thinks it’s evident that the initiation of agriculture was detrimental to health.

He’s concerned about human beings from an evolutionary perspective and thinks we couldn’t have been adapted to the new agricultural plant diet.

In our part of the world this comprised of a much more intense utilisation of cereals than previously. Mysterud points out that a diet based on cereal plants: grains, rice and corn is essentially different from what we and our ancestors have evolved to eat.

“We had two million years of hunting and gathering behind us. That is the way we survived longest and the majority of us are best adjusted to that diet,” says Mysterud.

Still paying the consequences

Mysterud thinks we are still suffering the negative consequences of the new agricultural diet and that we have yet to become genetically adapted to these new foods.

He is particularly concerned about cereals and says cereal products lack nutrition and their nutrients are not easily accessed by our bodies – they lack bio-accessibility. Cereals also contain anti-grazing compounds which they have evolved as a defence against wild herbivores. Some of these are toxins that can trigger negative reactions in humans.

Storage of cereals represents another danger from moulds, especially during rainy years in societies lacking modern storage facilities.

“The prehistoric diet was low-carb. From a long-term historical perspective the cereal-based diet is new and it should be studied in relationship to how well we tolerate it,” says Mysterud, who is also one of the editorial staff and a writer about health and nutrition for the health magazine Vitenskap & Fornuft (Science & Reason).

A portion of the population is allergic to gluten, which is found in wheat and several other cereals. Mysterud thinks this might be just the tip of the iceberg and that many of the ailments people encounter in modern society might stem from their body’s intolerance to cereals and flour.

The tale of graves

Archaeologists who have studied the skeletons from graves dating back to the dawn of agriculture haven’t provided any definitive results, but many agree with Mysterud that agriculture appears to have led to poorer health and reduced lifespans.

Solid evidence is missing but malnutrition and vulnerability when crops failed could be the cause.

Deficient health can in many cases be detected by premature deaths, poorer dental health and infections that have left their skeletal marks.

Agriculture can have led to greater workloads, more physical wear and less relaxation time for individuals, but there are too many uncertain factors to make a reliable estimate of average working hours 10,000 years ago.

Farmers had more children

The risk of infectious diseases mounted because people started living closer together with domesticated animals like pigs and cows. The storage of food also attracted disease spreaders such as mice and rats.

These negative effects of agriculture might not have been so evident in an early phase of the transition from the old way of life. Perhaps humans didn’t make the connection or the negative effects came later.

Intrinsic to the issue of reduced health is the matter of a population increase. Agriculture can have been so successful on the short term that it upset natural checks and balances. Studies indicate that women in agricultural societies had more children than women in hunter-gatherer societies.

Families with a permanent dwelling probably had more children than their nomadic sisters. A new diet that included milk from livestock as well as porridge could have shortened the period of breast-feeding infants.

Agriculture could thus have led to health deterioration for the individual but still brought about a population increase.

-------------------------------------------------------

Read the article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

Scientific links

- Brian Hayden: The Proof Is in the Pudding. Feasting and the Origins of Domestication, Current Anthropology, vol. 50, no 5, Oct. 2009 (abstract)

- Mark Nathan Cohen: Introduction: Rethinking the Origins of Agriculture,” Current Anthropology, , vol. 50, no 5, Oct. 2009 (abstract)

- T. Douglas Price and Ofer Bar-Yosef: The Origins of Agriculture: New Data, New Ideas. An Introduction to Supplement 4, Current Anthropology, vol. 52, supplement 4, Oct 2011.

- I. J. Thorpe: The Origins of Agriculture in Europe, Routledge London/New York 2009 (book presentation)