Genes reveal animal history

Reindeer living way up north today are immigrants from the south. This is revealed by their genes, which also divulge other secrets of these animals’ shared history with humankind for thousands of years.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

In prehistoric times our ancestors lived in conjunction with herds of wild horses and primal oxen. Today only the tame varieties are left – horses and cattle.

For most domesticated animals the transition from living wild and being tamed lies very deep in the past. However, genetics can tell the story of how humans and animals developed together in the course of millennia.

New genetic technology tells a previously unknown tale about a fairly new domesticated animal – reindeer in in Norway’s northernmost Finnmark County.

Stocks of domesticated reindeer and wild reindeer still live side by side in northern Scandinavia, Finland and Russia, just like wild and tame variations of horse and cattle co-existed in Europe, Asia and Africa.

Domesticated only for a few hundred years

For years Norwegian scientists have been mapping the genes of domesticated reindeer in Finnmark County and stocks of wild reindeer in the mountains of Southern Norway.

The tame Finnmark herds, which play a key role in the culture of the indigenous Sami people, are still very similar to their wild relatives, but they have distinct genetic characteristics.

Perhaps these animals are in an early stage of a development that parallels the evolution of the primal ox, wild boar and the wild sheep several thousand years ago.

“Many of the other animals were domesticated 10,000 years ago. The domestic reindeer only has a few hundred years behind it,” says Professor Knut H. Røed at the Norwegian School of Veterinary Science. He is one of Norway’s most recognized experts on reindeer genetics.

In 2008 Røed and colleagues concluded that reindeer had been domesticated in at least two areas of the globe – and one of these was in Scandinavia.

Bait for wild reindeer

Reindeer could have been tamed and used as lures in the hunt for wild reindeer in ancient times. They were also tamed for milking and for pulling a skier or a sled. Reindeer husbandry started on a large scale in Norway in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Finnmark is now Norway’s main domestic reindeer county and that could lead one to think this is where they come from. But it isn’t that simple.

“We don’t believe reindeer were tamed in Finnmark,” says Gro Bjørnstad at the University of Oslo (UiO).

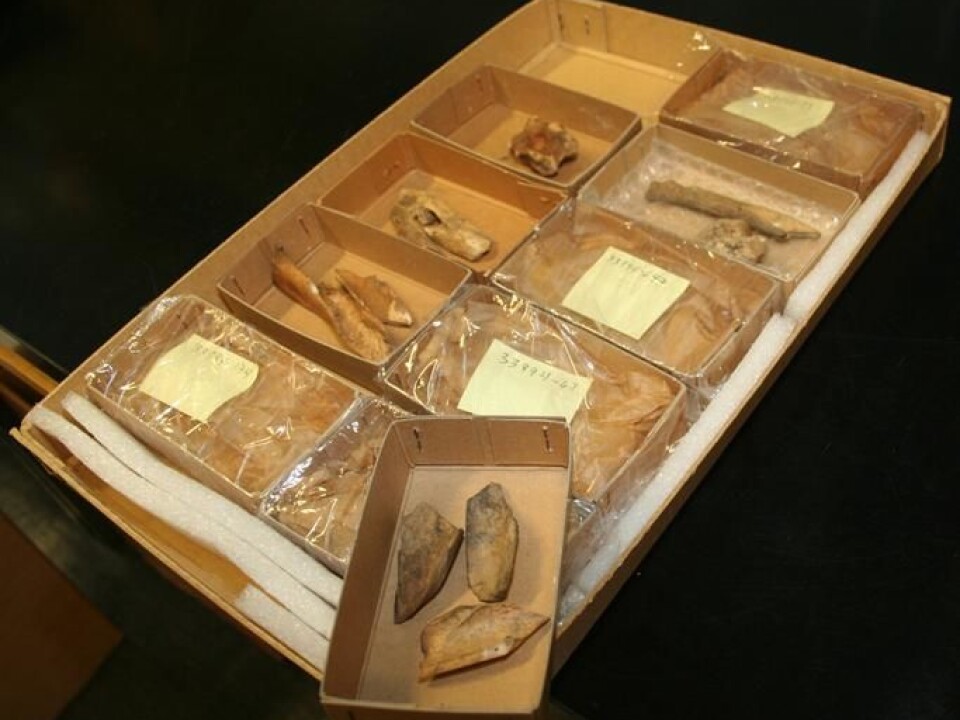

Bjørnstad is a genetic researcher who specializes in archaeological material – animal and human remains.

The raw material of her work is a fine powder taken from bones with a drill or by other means. This powder contains DNA which is isolated through a series of chemical processes before the genes can be mapped by gene sequencing.

Last year Bjørnstad, Røed and two other colleagues published their results from a study of the origin of domesticated reindeer in Finnmark.

5,000-year-old reindeer genes

The researchers extracted DNA from archaeological findings of wild reindeer from Finnmark prior to domestication, some of which were as early as 5,000 years old.

These bones come from settlements linked to Finnmark’s ancient hunting and trapping culture. These were then compared to genes from reindeer bones dated to the 1400s-1700s.

These have also been compared with the genes of present-day domestic reindeer in Finnmark, Russia and Finland.

Set of mutations

The scientists have studied selected sequences of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA).

MtDNA is passed from mother to child in an unbroken chain of females. Mutations in selected parts of this genetic material can be used as genetic indicators.

“A set of several mutations is characteristic of tame reindeer,” Bjørnstad.

She says these particular mutations are currently found in about 90 percent of domesticated reindeer in Finnmark.

The mutations first started turning up in skeletal remains from Finnmark around the year 1500 and are not evident in archaeological finds of wild reindeer from prior to domestication.

Tame reindeer around 1600

Researchers reason that today’s domesticated reindeer could come from regions further south in Scandinavia.

They could have been from southern Norway but also from northern areas of Sweden or Finland.

Written sources in Sweden tell of comprehensive herding of tame reindeer from around 1600.

The latest studies rule out the possibility of the taming in central mountain areas of Norway such as the Hardanger Plateau and the Rondane Mountains, where wild reindeer now roam.

In addition to economic and social factors, there could have been biological reasons for where the first domesticated reindeer were found. Different stocks of the same species could have developed distinct characteristics with varying degrees of suitability for close human contact.

Easy to spot a tamed animal

Just as genetic studies provide new knowledge about reindeer in Finnmark, a flood of research data is pouring in which aims to determine the origin of other, older domesticated animals such as dogs, pigs and cows.

“We already have archaeological expertise. Now we have molecular biology as a new tool for understanding the past,” says Professor Odd Vangen at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB) at Ås.

The changes from wild to tame are often plain as day. For instance we can immediately distinguish between a domesticated pig and the boar it descended from because it has a different colour and has less pronounced canine teeth.

But Vangen says the changes are much more extensive. Part of the most dramatic of these is their reproduction qualities.

Wild boars farrow at the same time every year and usually have a litter of 3-5. Domesticated pigs can farrow 10-14 piglets in a single litter and this reproduction is year round, rather than seasonal.

From a garbage eater to a porker

“All selection of animal traits has been guided by our preferences,” says Vangen.

Pigs have more meat on their hindquarters than boars, which have their centre of gravity further forward. Tame pigs even have more ribs than wild boars.

These changes have taken time to develop. Pigs haven’t always been fat factories. The pigs in Norway in the 1700s were outright skinny.

“As late as the 1700s pigs in Norway could be semi-wild in the summer season. They were allowed to run free outside of fenced areas and were generally very thin. Part of their task was to forage for any surplus garbage,” says Vangen.

After a while as the needs of society changed, pigs became producers of lard and a warehouse of surplus energy which could be slaughtered for Christmas. In the 1950s the pendulum began to swing back and consumers wanted pigs that had more meat and protein and less fat.

No clear answer

Although genetics represents a powerful tool for revealing the past, the field doesn’t always supply ready answers. For instance when it comes to canines a veritable dogfight is being carried out between those who think the animal comes from China and those who believe it originated in the Middle East.

Scientists also disagree about where cattle were first domesticated. For a long time the Middle East was seen as the original region. Contemporary research results are pointing in the direction of Sudan or other areas of North Africa.

One thing making it difficult is that 10,000 years ago humans started up with livestock based on herds of semi-wild animals. Perhaps this is how our ancestors culled these herds and changed them through selective hunting/slaughtering them in accordance to age groups, gender etc.

This model departs from another conception of the origin of animal domestication, which hypothesises that captured wild animals – or young orphaned offspring − were placed in pens and bred under controlled conditions.

Alternatively, if humankind has carried out a sort of management of wild animals which in some way resembles the Sami’s reindeer herding, their genes would have been altered very slowly. This would make it arduous for archaeologists to prove domestication.

The genes of agricultural plants could have changed very rapidly, whereas domesticated animals might have changed genetically at a snail’s pace.

Colonisers turned loose wild animals

Archaeological discoveries from Cyprus indicate that Neolithic people lacked a clear division between wild and tame animals. The Mediterranean island was colonised by a farming people around 8000 BCE.

The island supported a limited fauna. Its dwarf hippopotamus and dwarf elephants were extinct, either because of climate change or because of being unsustainably hunted. Archaeologists have however found skeletal remains of cats, dogs, pigs, sheep and goats. This indicates that the colonisers brought domestic animals along with them from the mainland.

But there are also plenty of bones from fallow deer, wild boars and foxes. So scientists think they could have also brought wild animals to the island and turned them loose to hunt. There are indications that goats had been wild for periods and hunted.

Human beings brought their ecological niche along with them from the mainland and established it on the island. Wild animals could also be caught and managed.

The lesson of reindeer

Professor Knut H. Røed at the Norwegian School of Veterinary Science thinks we can learn more about the ancient past through studies of the interplay between humans and reindeer in the recent past.

He refers to the relationship between genes and animal behaviour.

“Domesticated reindeer can thrive in nature totally on their own, as wild herds. But a certain degree of their tameness stays on,” says Røed.

“This must be genetic, and if we gain more expertise about the origin of this it will have an impact on our general knowledge of the taming and controlling of animals. Reindeer enable us to come closer to a process that occurred thousands of years ago with other animals.”

——————————————

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

Scientific links

- G Bjørnstad, Ø Flagstad, AK Hufthammer and KH Røed: Ancient DNA reveals a major genetic change during the transition from hunting economy to reindeer husbandry in northern Scandinavia, Journal of Archaeological Science, January 2012 (see abstract)

- KH Røed, Ø Flagstad, M Nieminen, Ø Holand, MJ Dwyer, N Røv and C Vilà: “Genetic analyses reveal independent domestication origins of Eurasian reindeer,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 22 August 2008

- J-D Vigne, I Carrère, F Briois and J Guilaine: The Early Process of Mammal Domestication in the Near East. New Evidence from the Pre-Neolithic and Pre-Pottery Neolithic in Cyprus, Current Anthropology, October 2011