The tiny island of Hitra was home to a large-scale cannery — without electricity or running water

As many as 18 canneries were in operation on the islands of Hitra and Frøya at the mouth of Trondheim fjord from the 1890s until 2011.

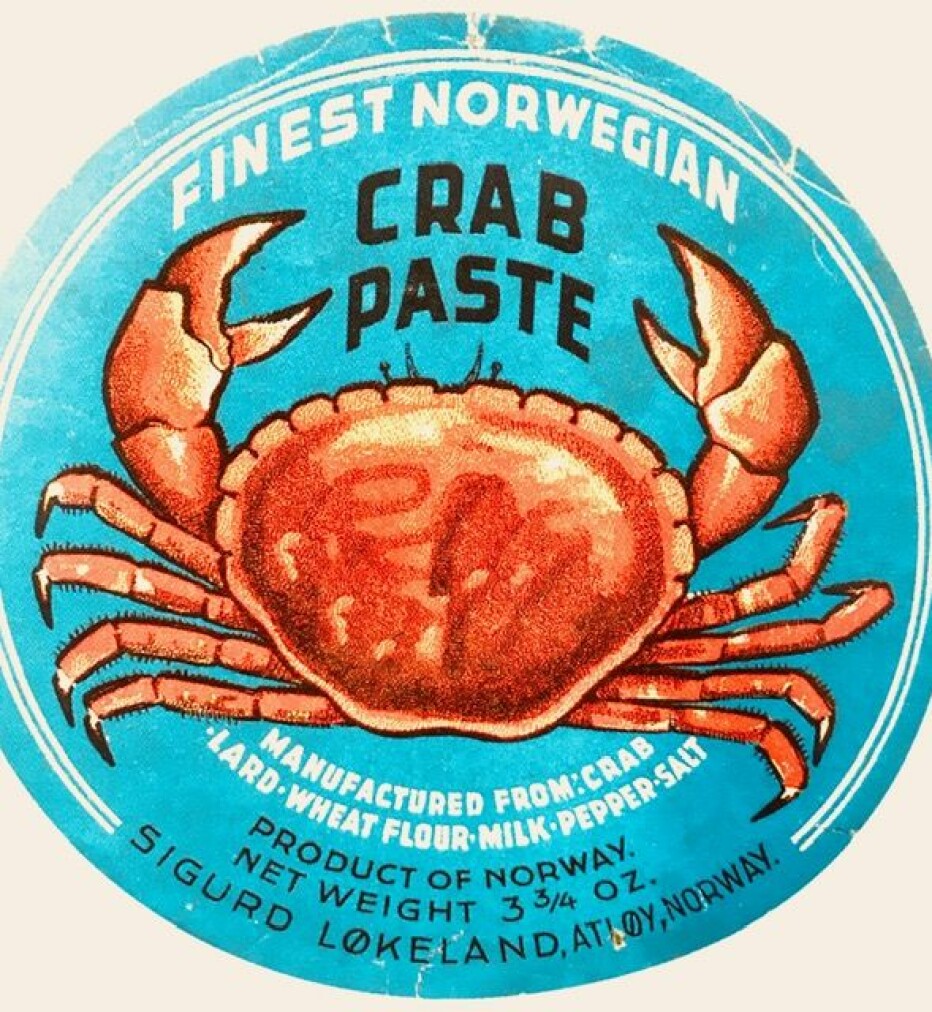

The first crab processing facility on the islands west of Trondheim started in 1913.

The first large cannery on the islands, Hitra Conservfabrik on Melandsjøen, was established in 1917. The demand for Norwegian canned food had skyrocketed since the outbreak of the First World War, which required a lot of food in the warring countries. Canned food was the solution.

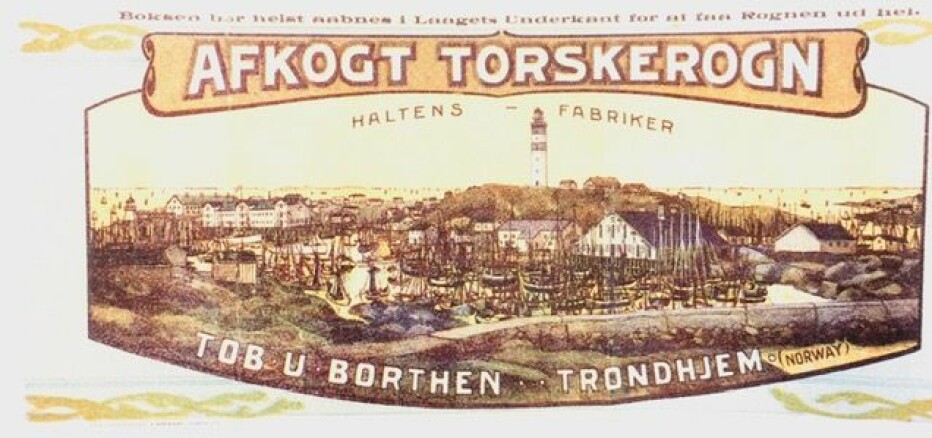

In 1922, the people of Sula watched in astonishment when Einar Boneng from Frøya docked with a large yacht furnished as a floating cannery where cod roe was canned.

He later built a cannery on land in Bonenget on Frøya.

The post-war era was a boom time

Canneries popped up like toadstools on the islands from the 1920s until the 1980s. From1946-1949 alone, 6 new canneries were established.

This particular industrial adventure on the Trøndelag coast only came to an end in 2011, with a fire.

This summer, the Coastal Museum of South-Trøndelag on Hitra presents the story of the canneries along the Trøndelag coast and their significance to the communities.

Hairpins, attempts to make pen pals via the cans themselves, and a lawsuit from France are some of the fun details.

What made the crab industry so large here, however, was access to natural resources, entrepreneurship and the sardine industry’s policy of forced cartels.

Amazed by what entrepreneurs achieved without electricity

Hans Jacob Farstad is a curator at the Coastal Museum on Hitra, and has a master's degree in cultural heritage management. He is project manager for the exhibition.

People on the coast lived in the midst of bountiful marine resources. But creating an industry based on these resources without electricity or running water wasn’t easy and is very impressive, he said.

«It strikes me as absolutely incredible what the entrepreneurs achieved with the few resources they had. They must have been driven by a strong creative urge, and the people of Trøndelag were incredibly active,» says Farstad, who himself is originally from the west coast of Norway, south of Trøndelag.

Canneries were even built on the outermost reefs and islets at the mouth of Trondheim Fjord in Frøya. There were two canneries in Mausund and one at Halten. At Gjæsingen, a village with only 250 inhabitants, there were two canneries.

«But one blew into the sea,» Farstad said.

The canneries first used manual crimping machines. Eventually the machines were connected to a boat engine or something similar. Water was introduced into the cannery via collected rainwater from the roof. Before the islands were electrified in the 1950s, they fired steam boilers with coal, coke and firewood.

Female Workplace

When sardine fishing became strictly regulated in the 1930s, people began to look at crab — a previously little used resource. The demand for raw materials for the canneries meant that fishermen could finally make money fishing for crab.

The men steamed the crab in big pots on the piers. Men also punctured the crab claws inside the cannery.

But the work of cleaning the crabs and packing the meat in cans was dominated by women. It was a real chore to extract all the crab meat, and the work had to be done by hand. The women mounted hairpins on handles to get all the meat out of the claws.

More than 70 per cent of the workers in the canneries were women. The crab industry was one of the first jobs available to women along the coast who wanted paid employment.

«It meant everything, not just the money, but getting out among other people,» one of the women said to a Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) reporter in a TV feature from Mausund.

Wrote their names on the back of the label

In the interview, the worker admitted that they used to put pieces of paper under the labels that were to be sent out into the world. What did they write?

«We wrote that we are 16-17 years old,» she said. But their efforts never resulted in foreign suitors.

The label was last thing that was put on the can.

«I remember we used to write our name, age and address on the back of the label. It was always exciting to wait for an answer from someone. We got replies from both home and abroad,» said Janne Karin Åshammer, who worked at Bekken Fiskesamvirkelag.

«Once I was tempted to write the name of the oldest of the women, and wrote that she was 19 years old. She got a letter from a handsome sailor who was just under 30, who thought he was a little too old for her,» she says.

France sued Norwegian sardine canneries

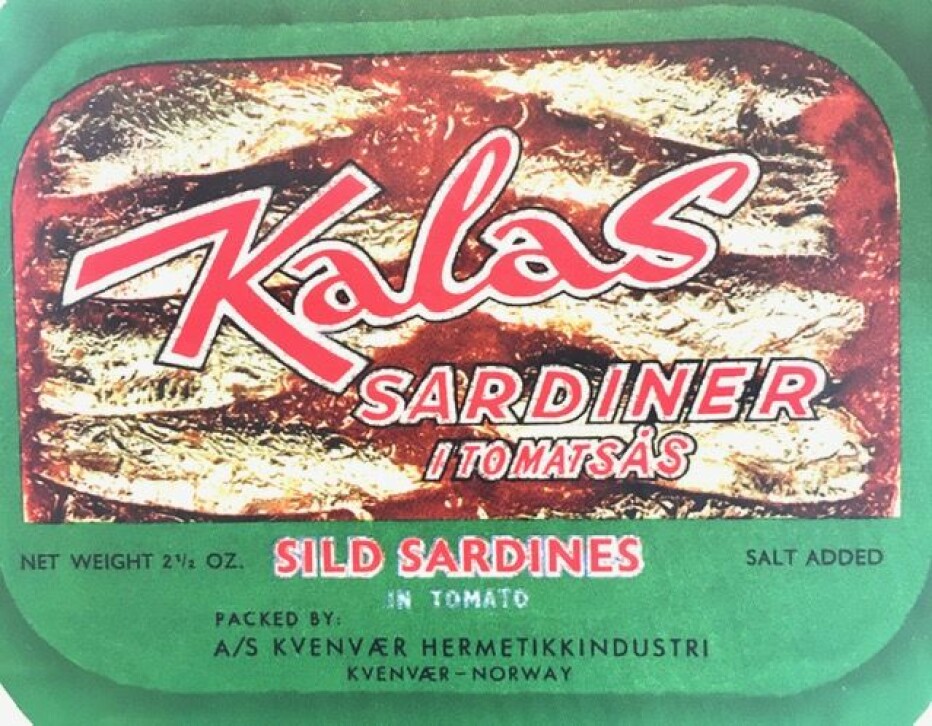

Before crab, most of the canneries processed sardines.

But in 1914, France sued Norwegian canneries over the use of the word «sardine», to which the French believed they had exclusive rights. The Norwegian canneries lost the lawsuit, and instead used «smoked sprat» or «smoked herring» as the name of the product on the cans.

In the 1930s, Norwegians canned and sold fish balls, cod roe, cod milt, whale meat and sole as well as mackerel in oil. The canneries produced canned meat as baby food. Zooplankton was sold as feed for aquarium fish.

World War I increased the demand for canned food. In 1934, 850 people worked in this industry in Trøndelag. The 1940s brought explosive growth. The number of canneries doubled on the islands.

More and more canneries were established on the islands of Hitra and Frøya after World War II.

But the oil crisis in 1973 was a catastrophe for many canneries.

After the 1970s, more canneries began to close. Norway had become a high-cost country, and Norwegian canned food wasn’t competitive on the export market.

It was no longer profitable to employ hundreds of workers.

Canned food as assistance through the UN

In 1994, five Trøndelag canneries delivered canned mackerel in oil to the UN food programme to help developing countries. Three of the canneries were on Frøya. But in 2006, this programme ended.

Then Titran Canning burned down in 2011 — which marked the end of the production of canned goods in that coastal community.

But many of the business owners had already sought other opportunities.

«Several of the canneries, including Astor Canning on Hitra and Bekken Fiskesamvirke on Frøya, switched to investing in the aquaculture industry,» says Farstad.

Tough to create the collection

The history of the canneries is based on a number of oral and written sources.

«Several of the canneries had intact archives, so we’ve gotten a lot from there. In addition, I have reviewed the cannery inspection reports and protocols for the area, which have provided insights into working conditions, gender division and the number of workers,» Farstad said.

Pictures of the products and the workers were drawn from various sources.

The 2019 Yearbook for Skarvsetta includes more detailed information about the canning industry and the canneries.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

The time of canning. Exhibition about the cannery era on the coast of Trøndelag, Coastal Museum of South-Trøndelag, Hitra. 2020.

Svein Bertil Sæther, Hans Jakob W. Farstad and Svend Sivertsen: Yearbook for 2019, Skarvsetta. The time of canning. The Hitra History Association and the Coastal Museum of South-Trøndelag (in Norwegian).

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no