These bones could rewrite the history of life

Everyone believed that the mighty ichthyosaurs arose in the wake of the Earth's biggest catastrophe. But a new Norwegian discovery suggests instead that these ancient lizards already existed — and survived the inferno 252 million years ago.

It was the worst thing that has ever befallen life on Earth.

Some 252 million years ago, the largest known volcanic eruption in the history of the planet took place. An area six times larger than Norway was covered by a 2,000-metre-thick layer of lava. The atmosphere was filled with greenhouse gases and other noxious substances, and the global temperature increased by 10 to 15 degrees.

Sea temperatures of up to 40 degrees and large oxygen-free areas killed at least 80 per cent of all genera in the sea. Maybe as much as 95 per cent. Many land-based animals and plants also died out.

“It was much worse than the disaster that befell the dinosaurs,” says Jørn Hurum, a Professor at the Natural History Museum in Oslo.

The dinosaurs went extinct in a great catastrophe about 66 million years ago. But the enormous volcanic eruption occurred much earlier and was even more devastating. It took millions of years before life was able to recover.

The story of the ichthyosaurs

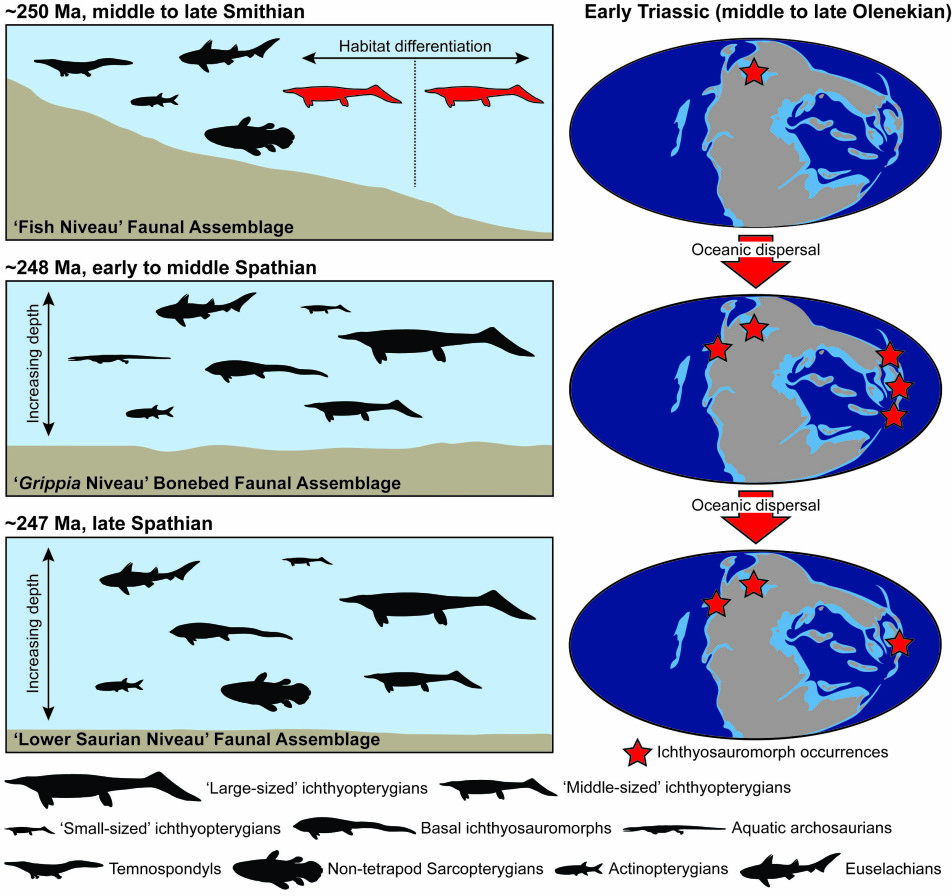

It is during this period — just after the catastrophe 252 million years ago — that it was thought that ichthyosaurs evolved.

Ichthyosaurs were initially terrestrial animals with lungs that returned to the sea and became completely aquatic, just like living marine mammals, such as whales and dolphins.

The oldest ichthyosaur fossils have been found in 248-million-year-old geological layers, or around four million years after the mass extinction. From there the numbers and varieties of these animals skyrocket. Different kinds of ichthyosaurs – from animals the size of dolphins to whale-sized giants over 23 meters long – spread throughout the world’s oceans.

“This is the story that has long been told and appears in all the textbooks,” Hurum said.

But now a handful of grey lumps from the Norwegian archipelago Svalbard, in the Arctic Ocean, have changed everything.

Found behind cabins

The find originates from an excavation site very close to the cabins at Vindodden on Svalbard.

There, Hurum and his colleagues unearthed fossils of fish and marine amphibians in 250-million-year-old rocks. But in 2022, another collaborator arrived – Benjamin Kear from Uppsala University. He looked through the fossils from the excavation with new eyes.

Then something caught his attention: some grey lumps —fossil bones —which the other researchers had not quite managed to place.

They looked exactly like the caudal (tail) vertebrae of an ichthyosaur —but originated from the time before ichthyosaurs came into existence.

What was that all about?

An ichthyosaur from the time before ichthyosaurs

After a thorough investigation of the fossils and the rock that contains them, Kear, Hurum and the other members of the research group have no doubt:

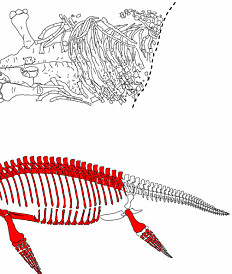

These are the remains of a large ichthyosaur. Also, the fossils represent not just some amphibious walking ichthyosaur ancestor with webbing between its toes, but a fully aquatic ichthyosaur, shaped like a fish.

“These are the bones of a really good swimmer. The tail vertebrae are virtually identical to those of advanced fully oceanic ichthyosaurs,” Hurum said.

At the same time, the rock surrounding the fossils contains signs that it was formed before the first ichthyosaurs supposedly came into existence.

The same deposits contain the fossils of fish and amphibians that are typical of 250-million-year-old ecosystems. And the chemistry in the stone points to the same time.

It raises staggering questions about the history of ichthyosaurs.

Are they significantly older than everyone thought? And does that mean they actually survived the most devastating ecological disaster in the history of life?

Too soon after the disaster

Hurum believes the find means that textbooks will have to be rewritten.

“This fossil is from a very brief time —only two million years —after the great extinction,” he said.

That’s simply not enough time for such an advanced ichthyosaur to develop.

“The other story like this involves whales. Just after the extinction of the dinosaurs around 66 million years ago, some land animals wandered about near the water's edge, walking on four legs. But within a few million years they could no longer walk on land,” he said. “After around eight million years, they are completely aquatic.”

This leads Hurum and his colleagues to think that ancestors of the new ichthyosaur from Svalbard must have been fully aquatic when the volcanoes erupted.

No doubt about the dating or the animals

But isn’t it possible that Hurum and his colleagues are wrong about the dating or type of animal?

Professor Martin Sander from the University of Bonn doesn’t think so. He is a palaeontologist that also specialises on ichthyosaurs but was not involved in the study.

“The dating of the locality on Spitsbergen is unequivocal, as is the global dating. It also is very clear that the fossil is that of a large ichthyosaur,” he wrote to sciencenorway.no.

“The great age of the fossil, only a few million years after the beginning of the Triassic, combined with its large size is amazing,” he wrote.

Sander agrees with Hurum.

“We can no longer be sure that the invasion of the sea by reptiles happened in the Triassic, after the great extinction at the end of the Permian. There simply is not enough time,” he said.

On the other hand, he points out that there is not a single bit of evidence of ichthyosaur ancestors from before the disaster.

So where on Earth did this fully formed ichthyosaur come from?

Out in the depths and up in the north

Hurum suggests that the animal may have lived further away from the coast, and in deeper water, perhaps even further north than the discovery site on Svalbard.

In fact, 250 million years ago, Svalbard was a bay on the northern coast of the supercontinent Pangaea.

But Hurum wonders if there might be something further north.

Perhaps there was an ocean with deep water areas that supported an undiscovered, food chain with ichthyosaurs at the top?

If so, then that could explain how ichthyosaurs survived the disaster 252 million years ago. Temperatures may have been more stable in the far north, so that ecosystems did not completely collapse.

But why haven't we found more remains of these early ichthyosaurs on Svalbard?

Where should we look?

It is conceivable that these animals weren’t used to staying in areas that make up today’s Svalbard, Hurum speculated. The fossil tail vertebrae may originate from an individual that strayed from its typical habitat and ended up in a shallower coastal area.

It could be similar to Freya the walrus, the young female walrus that wandered from her Arctic home in 2022 and cruised the coastlines of northern Europe, including Norway.

Perhaps palaeontologists need to look for other early ichthyosaurs in completely different areas. The problem, however, is that they don't know where to start.

Many of the areas that existed at that time have completely disappeared today. And even if these areas could be explored today, it is still not certain that they would contain fossils. Not all rock types preserve fossils equally well.

“We have few deposits to look for this far north on Pangaea. In Svalbard, we have deposits from the period before the extinction, but the conditions for preserving bones are not so good,” Hurum said. “So where can we look? Do we have to go to Alaska or Siberia? Or Franz Josef Land?”

It’s not even certain that remains from a possible far northern Triassic Sea have been preserved at all.

May already have been found

On the other hand, there is no reason to give up.

New expeditions can suddenly yield more discoveries. And in the meantime, it’s also possible to search in much more accessible places: museums.

The grey lumps from the excavation at Vindodden are not necessarily the only ichthyosaur fossils that have been overlooked because they did not fit in with what previous researchers expected to find.

“We can start by looking at old collections again,” Hurum said.

With luck, the next evidence of the ichthyosaurs' early history may already be waiting in a pile of indeterminate finds from previous excavations.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

B. P. Kear, V. S. Engelschiøn, Ø. Hammer, A. J. Roberts & J. H. Hurum, Earliest Triassic ichthyosaur fossils push back oceanic reptile origins, Current Biology, March 2023. Abstract.