Discovered new species on Svalbard: Britney was an arctic plesiosaur with a tiny head and enormous eyes

Researchers have learned more about an ancient, nearly headless family of prehistoric animals.

In 2012, Aubrey Roberts and the rest of the "lizard digger team" refused to give up, in spite of wet weather on the arctic archipelago of Svalbard. It was then that they made the discovery.

The expedition lasted two weeks, and the palaeontologists were examining parts of a geological formation called the Slottsmøya Member.

The formation hides traces of what lived in the north during the period of the Upper Jurassic to the early Cretaceous. This was the time when the dinosaurs walked the Earth.

But this particular geological formation on Svalbard contains what was found in the sea. One-hundred-and-forty-seven million years ago, the continents looked different, and the sea level was different, too. What is now a mountain was once a seabed.

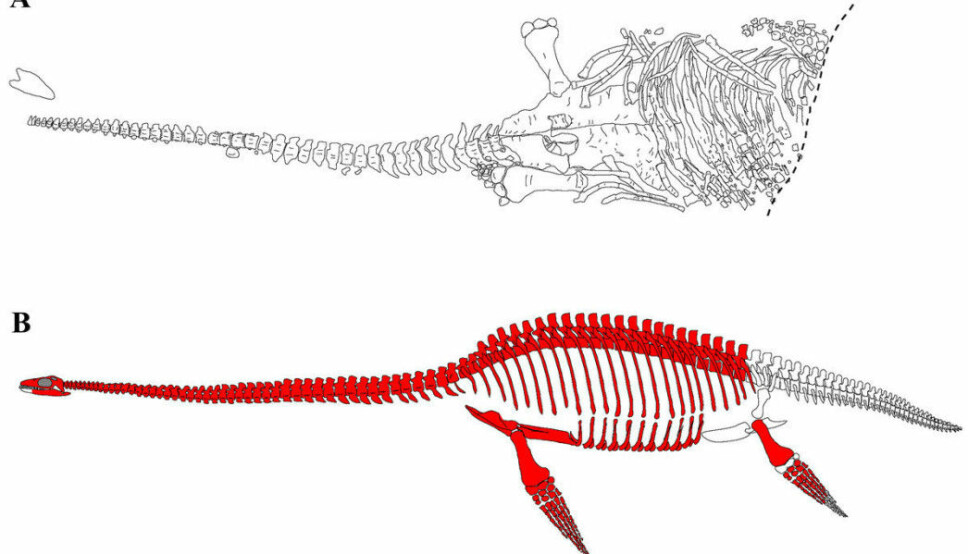

Buried in the ancient sediments, researchers found bones from several plesiosaurs and other marine animals. Then a nearly complete skeleton of a whole new species emerged.

The description of the animal is now published in the journal PeerJ.

Sea monsters of the past

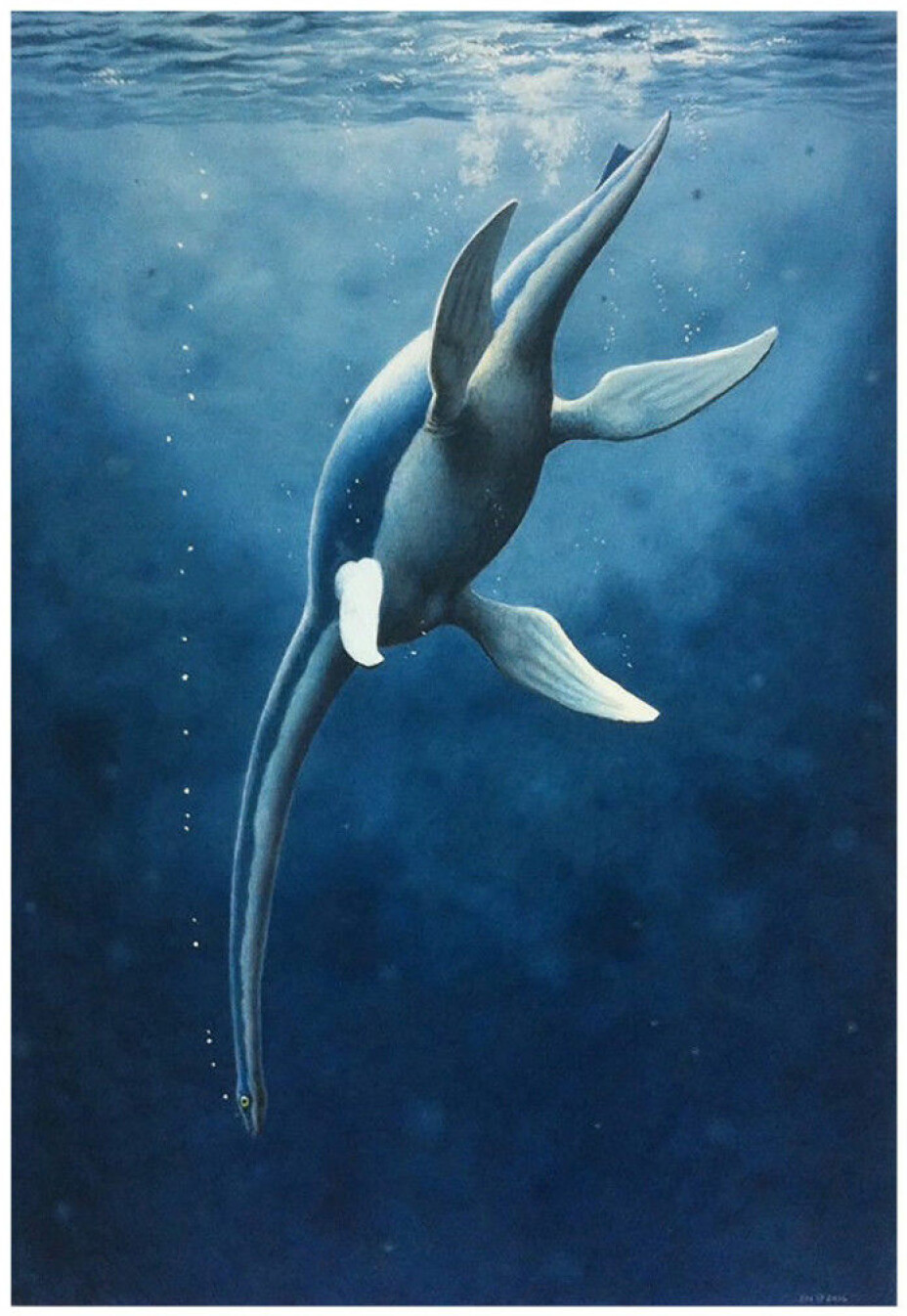

Plesiosaurs were reptiles that lived in the sea. They breathed with lungs and had to surface to breathe.

Some had extremely long necks, large bodies and flippers. It used to be thought that they held their heads straight up out of the water, but that was later disproven.

These "sea monsters" were among the first animals from the time of the dinosaurs that were discovered in the 19th century.

Their ancestors lived on land and crawled back into the sea again, much as the ancestors of ichthyosaurs, whales and seals did.

Some plesiosaurs, the pliosaurs, had a short neck and a huge head, and included species that were the largest predators that ever lived in the sea.

And then there was Britney

Jørn Hurum, a palaeontologist and professor at the University of Oslo’s Natural History Museum, led the team on Svalbard in 2012. Among the other lizard diggers was Aubrey Roberts, then a master's student at the Natural History Museum.

Erik Tunstad was a volunteer blogger, and published the story of the expedition on forskning.no (in Norwegian).

The team came across bones from several animals, but one discovery turned out to be especially promising.

"A little way into the Cretaceous layer is the plesiosaur that Julie and Øyvind have been working on in recent days," Tunstad wrote on the blog.

"The excavation is a dirty hell and for some reason the animal has been nicknamed Britney — Dirty girl? She lies with her butt sticking up — her neck disappears into the mountain,” he wrote.

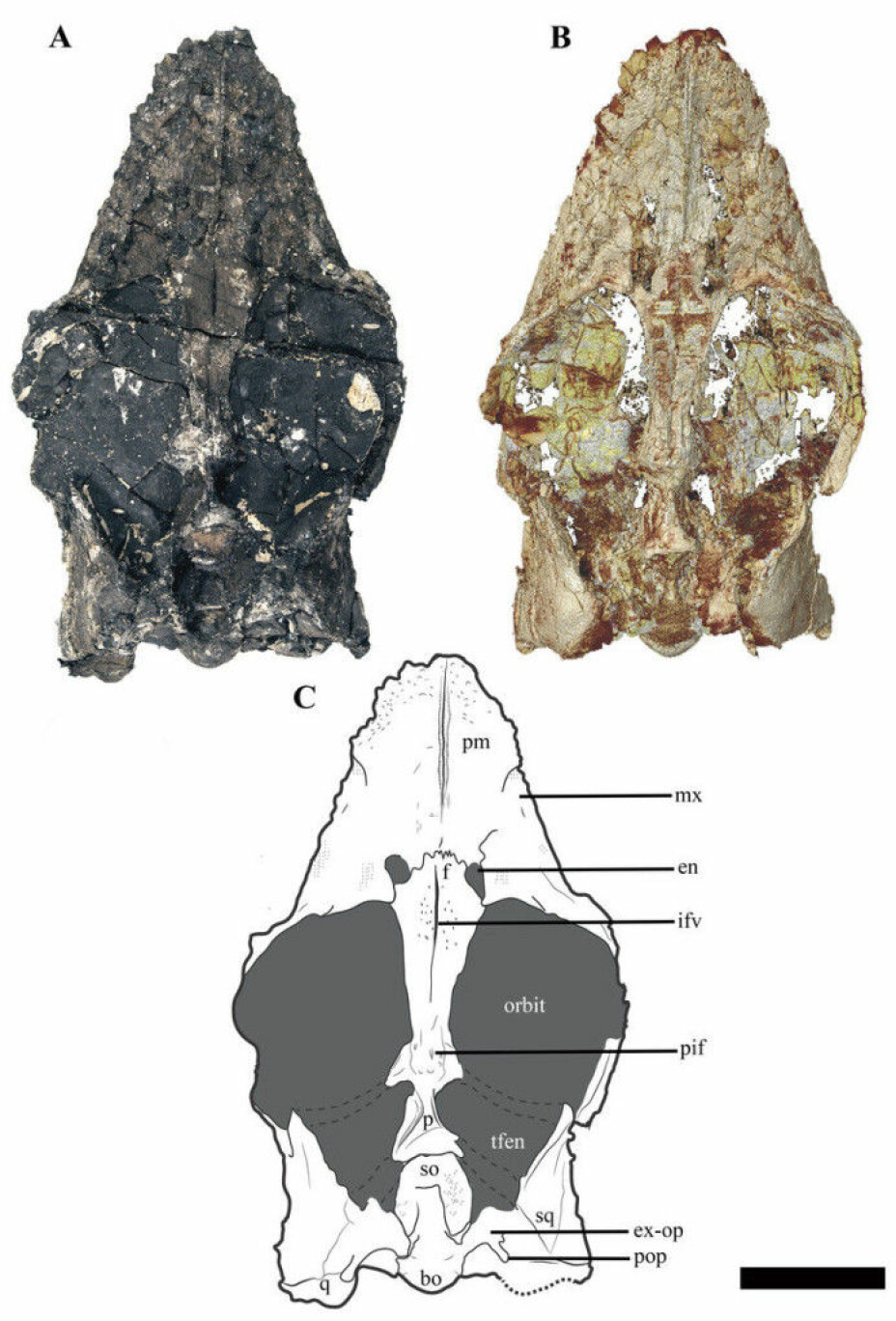

The researchers hoped there was also a head inside the mountain somewhere. The heads are rarely preserved in long-necked plesiosaurs.

At the last minute

The team dug out all the animal’s vertebrae. Spades and chainsaws were used to cut through the permafrost. Then they picked at the soil by hand to gently remove the neck vertebrae. But there was no head in the end.

It was their last day and it looked like they had to give up. But Patrick Druckenmiller of the University of Alaska continued to peck away at the ground. Not where they found the end of the neck, but a little further away.

And he found the head.

“We had dug for a week to try to find that skull, so we were disappointed when we didn't see it. We really deserved to find it,” Roberts says.

Only a few heads have been preserved from this group of plesiosaurs, called cryptoclidids, she says. Their skulls are small and fragile.

"The vast majority of plesiosaurs of this type have been found without heads," she says. “But not our species.”

The palaeontologist has finished her doctorate on the complete skeleton of the plesiosaur. The new species has been named Ophthalmothule cryostea, which means north-eye and frozen bones, Roberts explains.

“We named it that because it is found far up in the north, has very large eyes and was found in the permafrost. We think it fits,” she says.

An outstanding find

“This discovery is unique and is the only one of this group of plesiosaurs in the world with a preserved skull,” Hurum writes in an email to forskning.no.

He led the work on the excavation and is the last author on the study.

“Its strange shape, with a very small head and large eyes, is also very atypical for plesiosaurs, to an extreme degree,” he writes.

The work of preserving the bones took a long time.

“We got the whole fossil home, and spent several years preparing it. It often takes up to 2,000 hours to prepare and glue everything together,” says Roberts.

The researchers have also taken time to describe the skull so that other researchers can use the information. They also CT scanned it.

“We made reconstructions of the entire skull in 3D. It's really cool because we can actually see structures inside the skull that we can't see on the surface,” says Roberts.

There was not much room for a brain in there. But there was plenty of room for eyes.

“Most of the skull is actually eyes,” she says.

The big beast was 5 to 5.5 metres long. But the head was just over 20 centimetres long. That’s very small compared to the body, says Roberts.

Ate soft-bodied creatures, like squid

So what did this critter do with its big eyes?

The scientists do not know yet, but they discuss the possibilities in their article.

“It probably used its big eyes to hunt and find its food. Maybe down in dark water. That's what we've been thinking about,” Roberts says.

At the time the plesiosaur was alive, Svalbard was just about where Oslo is now. It was darker in the winter. Another possibility is that the plesiosaur used to root around in the seabed for food.

“We have calculated the strength of its jaw. It's quite small. It had very weak jaws,” she says.

It probably hunted for soft-bodied animals, such as squid and maybe small fish.

“And squids tend to be found quite deep,” she says.

In the same seabed layers found on Svalbard, researchers can also see what other animals lived at that time.

There were pilosaurs there, heavy predators that probably considered everything around them to be edible. There were several different types of ichthyosaurs, which were a type of dolphin-like reptile.

There were squids with shells that looked like snail shells, called ammonites, and squids without a shell. And there were fish.

New species from the Arctic

Aubrey Roberts summarizes the group’s finding like this.

“We have described a new species and genus from the Arctic. This increases the diversity that we know of in the layers from the Jurassic to the Cretaceous on Svalbard. And the species is very important for understanding the skulls of the otherwise headless species in the plesiosaur family.”

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

Reference:

A.J. Roberts et.al: “A new plesiosaurian from the Jurassic–Cretaceous transitional interval of the Slottsmøya Member (Volgian), with insights into the cranial anatomy of cryptoclidids using computed tomography”, PeerJ, 31 March 2020.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no