Heavy water mission that failed

In a hazardous initial attempt to sabotage the heavy water plant at Rjukan in Norway, 41 young Allied soldiers died. A soldier who was stricken from the roster for this mission, which was aimed at stalling Nazi Germany’s development of an atomic bomb, tells the inside story.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

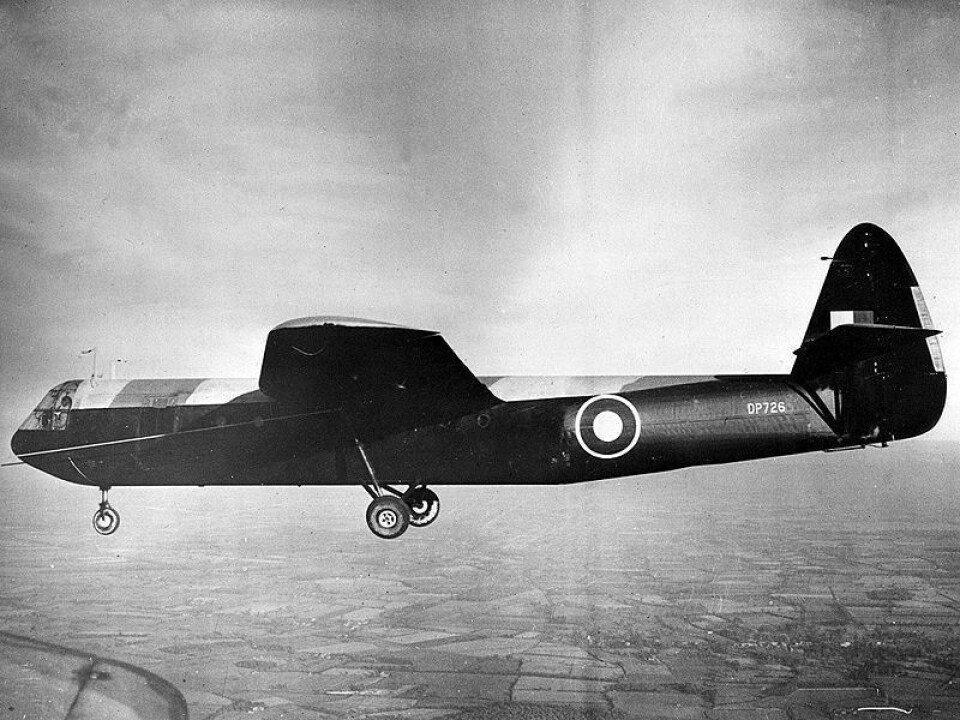

On the evening of 19 November 1942, three months before Norwegian resistance heroes sabotaged the heavy water plant at the town Rjukan, two bomber planes taxied up the tarmac outside the Scottish coastal town of Wick.

Two gliders were connected to the bombers on long hawsers. In addition to the flight crews, the four aircraft contained 48 young engineers from the British Commonwealth.

Many of them had written final letters home to their families, wives and girl friends – one has written home that they should have Christmas dinner ready when he returns.

It turned out to be a fiasco because of high risks and technical failure. Its history also testifies to the sacrifices of individuals and their families in war that was forgotten in the shadow of the victorious Allies’ success stories.

This is pointed out by Associate Professor Ion Drew at the University of Stavanger’s Department of Cultural Studies and Linguistics.

In a book he co-authored, the stories of men who took part in Operation Freshman have now been told in previously unpublished notes from a soldier who was injured shortly before the mission and taken off the roster.

Wrong from the start

Weaknesses in the operation started to become evident even before the aircraft left Scotland.

The communications wiring that was woven into the hawsers between the bombers and the gliders was on the blink and the only way for them to communicate was by flashing lights. But the operation wasn’t scuttled because of such a detail.

“It had now become dark and they departed. The gliders released their take-off wheels and I will always remember the sight of the orange parachutes that allowed this gear to drift back down to the ground. The planes changed course and were gone forever.”

The English engineer soldier Syd Brittain recounted this much later. He took part in all preparations for Operation Freshman, but a few days before the flights to Norway he injured a foot during an exercise and was taken off the list of active participants.

In the book written by Ion Drew and three colleagues about Allied war graves in the Stavanger area, Syd Brittain’s account is published for the first time.

A witness who should have been there

The British hobby historian Peter Yeates convinced Brittain to tell about his experiences with the operation.

Brittain was initially reluctant because from the moment he joined up he was sworn to secrecy. Until then he hadn’t even told his story to his family.

But he recounted it to Yeates, who recorded it on tape. Yeates later turned all the material over to Drew and his colleagues.

Brittain’s tale included a description of when he was sitting in a room with other soldiers and a colonel asked for volunteers to top secret and vital mission.

The colonel said the mission could be pivotal in preventing the enemy from deciding the war in its favour within six months.

After he was finished he said that those who didn’t wish to participate in the risky mission were excused and could leave the room. Everyone remained where they were, Brittain recalled.

It would have required more courage to get up and leave the room than to stay seated and consent to the mission, he reflected.

Conditions on board

The airplanes took off from Skitten despite technical problems and were soon just dots in the dark sky over the North Sea. Syd Brittain says that during training flights they sat in their sleeping bags because it was so cold.

“But we don’t know if they did that during the actual operation. But we know that it must have been terribly uncomfortable,” says Drew.

A description from Operation Pegasus Bridge, in which soldiers were supposed to blow up bridges in Normandy on D-day 1944 using the same type of glider planes, can indicate what it was like for the soldiers crossing the North Sea, he thinks.

“The soldiers sit facing each other in two rows, buckled in with belts in a cabin that could remind you of a crowded subway car.”

“Some are vomiting because they are being tossed around. Although the landing during Pegasus Bridge was described as perfect, the entire crew lost consciousness for a few seconds when they hit the ground,” says Drew.

Considered himself lucky

Four Norwegian agents had parachuted to a spot nearby the landing area from 20 to 30 October. They were supposed to prepare and mark a landing strip for the gliders and receive them when they arrived.

The first Halifax towing a glider left Scotland at 5:50 PM. It was delayed after an attempt at repairing the communications between the bomber and the glider.

The commander aboard the glider was the 20-year-old Scottish lieutenant Methven. He wasn’t originally supposed to be with the troop but was brought in as a replacement for an officer who had been injured in a shooting accident.

Just prior to departure, Methven wrote home to his parents that they needn’t worry about him if they didn’t get mail for a while, because he was heading on an excursion. He added that he was lucky to get the chance.

Third complication: Icing and turbulence

When the first plane neared the Norwegian coast the operation encountered its second big problem. Its compass failed and it became difficult to navigate by charts.

After making an attempt, the pilots decided they had no chance of finding the right valley to land in – Norway simply had too many of them and the weather had turned worse. The pilots decided to return to Scotland.

They had to fly high over the clouds and the tow line to the glider iced up. When they took the plane down below the cloud level to warmer air they ran into heavy turbulence. The hawser that pulled the glider full of soldiers snapped.

The troops were just north of Stavanger, and the glider crashed into a mountain in Fylgjesdalen at the Lysefjord. The Halifax, however, made it back to the airbase it had left earlier in the evening.

Radio operator Eric Otto explained later that the bomber had also iced up and he was certain that it had been hit by anti-aircraft fire when actually what happened was that lumps of ice were being slung into the fuselage by the propellers.

“The Halifax had a de-icing system on its wings and it worked. But the gliders were icing up too, and they had no such devices,” he explained.

Norwegian sheriff notified the Germans

Both pilots and six of the soldiers died instantaneously when the glider crashed in Fylgjesdalen. Some of the surviving soldiers sought help from a local farmer who in turn notified the local sheriff.

The sheriff felt it would be impossible to keep medical assistance secret from the occupying German forces, so with the consent of the soldiers, he got in touch with the security police, according to Drew.

“Among the nine who survived this crash was 25-year-old Trevor Louis Masters. He was injured and he showed a picture of his pregnant wife to Hjørdis Espedal, one of the Norwegians who come to their rescue,” says Ion Drew.

But the Germans had no intention of letting the British POWs slip away and placed them under arrest. The orders from higher up were to kill all the wounded, in accordance with Hitler’s Commando Order, but the rest were to be sent to Oslo for interrogation.

“Four of the men were doped with morphine and then killed. Heavy rocks were attached to their bodies and they were tossed into the sea,” says Drew.

Brutal executions

The authors have refrained from detailing the executions in the book, partly because they have been described in earlier accounts, according to Drew. But they were described as brutal and messy.

One of the soldiers was shot from behind as he was descending some stairs, but the others were strangled.

“It was a brutal execution and we wonder why it was done this way. The soldiers were injured and the German doctor claimed this is why they were given morphine.”

“It is unknown whether the intention was to kill them with overdoses.”

The German doctor was later given a death sentence for his role in the soldiers’ liquidation.

“It seems like they might have been given increasing dosages of morphine but they didn’t die from it. Finally they were simply killed outright,” says Drew to forskning.no.

Another problem: Conditions in Norway

The second bomber and the glider it was towing crashed at Helleland near Egersund, probably because of inclement weather and icing, explains Drew.

The glider crashed at the mountain Benkjafjellet and the bomber at Hæstadfjellet. All seven in the glider were killed instantaneously when it struck the ground.

“Together with the two Halifax pilots the 25-year-old driver Ernest Pendelbury died of injuries shortly after the crash, but 14 men survived and 11 were actually in pretty good shape,” he says.

Two of them made their way to the sheriff’s office at Helleland in the middle of the night. The sheriff said the Germans needed to be notified if a rescue mission were to be launched.

But some Norwegians made it to the site of the crash before the Germans got there to warn that the enemy was on its way to the wreckage. Despite having a little head start, Lt. Allen decided that they should surrender because it would be nearly impossible to make it all the way to Sweden.

The soldiers had civilian clothes on underneath their uniforms. This was a tactic meant to help them mix in with Norwegians on their planned escape to Sweden following the sabotage mission.

The Germans reasoned that the captives were commandos. They also found sabotage equipment in the plane wrecks and Col. Probst, the head of the Wehrmacht in the Stavanger district, had them sentenced to death as partisans.

Could Norwegians have rescued them?

Drew says speculations circulated about whether the sheriff who notified the Germans had been a Nazi sympathizer, but this has been ruled out later. It was natural for Norwegians to fear reprisals and not easy for them to do much more to help the injured men, thinks Drew.

“There had been cases of reprisals earlier, and I don’t think they had much choice. We who have worked with the material and know the chain of events have come this conclusion,” says Drew.

He also emphasizes that the soldiers decided to surrender, both because of the difficult terrain and because some of them were wounded. They must have known that it would be hard to escape so they turned themselves in, believing they would be treated like prisoners of war.

“I also think this was compounded by communication problems. The locals and the English speaking soldiers probably couldn’t communicate very well and the sheriff found it best to follow normal procedures,” says Drew.

Not much chance

He doubts that the soldiers would have survived even if they had landed the gliders successfully and sabotaged the heavy water plant.

“Every link in the operation was precarious,” he says.

The escape plan was for the men to walk to Sweden after blowing up the plant. This in itself was pretty optimistic, thinks Drew.

“These boys couldn’t ski. Just think of Eastern Norway at the end of November with the entire German Occupation Army in Norway on their heels.”

“They had learned a few Norwegian phrases, such as ‘I’m going to the dentist’ and the like, which was pretty ridiculous, all things considered,” says Drew.

Controversial mission

The operation was so secret that even the families of the operatives were kept in the dark for years after the war before being told what had happened to their sons and husbands.

It was a controversial attack, which its leader Colonel Henniker, mentioned in his memoirs. Retrospectively he criticized the entire mission openly, according to Drew.

“In his writings Henniker says he was against its implementation, partly because it was too risky, and because the training period was too short,” Drew says.

Commandos with short training

Much of the reason why the failed mission was stamped secret by the British authorities for 30 years was that it was highly unconventional.

For one thing the soldiers were wearing civilian garb under their uniforms. According Syd Brittain they had been instructed to look rather shoddy. They had been ordered to grow their hair long so they didn’t look like soldiers, he recalled.

“Their training, which included how to silently kill guards without firing a shot, was something that commandos learn now, but it was pretty uncommon then.”

“But these boys weren’t really commandos – they were Army engineers and many of them had come from vocations such as carpentry,” says Drew.

In the shadow of Norwegian heroes

Many Norwegians today have never heard of this first attempt to destroy the heavy water plant at Rjukan. One reason of course is that it was held secret, thinks Drew.

But there are other reasons too – for instance that success stories are more often told than fiascos. In addition, the successful sabotage of the plant in February 1943 was carried out by men that were better suited to be viewed as Norwegian national heroes than the foreign Freshman crew, he thinks.

“The Norwegian mission was also presented in the Hollywood film The Heroes of Telemark, with stars such as Kirk Douglas,” says Drew.

But the failure of Operation Freshman does not make Ernest Pendlebury, Trevor Masters and their comrades less heroic, he thinks.

Letters, interviews and other source material that he and his colleagues studied in their work with the book reveal that the participants in Operation Freshman thought being part of such a mission was exciting, but that didn’t mean they were any less in fear for their lives.

“Some of them probably had their doubts. Nevertheless, they did their duty. You have to admire them and they shouldn’t be forgotten,” says Ion Drew.

--------------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling