From oil city to energy city

Oil city Stavanger is looking for a new label more suited to a post-petroleum era. The search for a new moniker is part of the south-western coastal city’s long history of identity shaping.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Stavanger is Norway’s Oil City – an iconic concept that the city has built its identity on since the country’s offshore oil adventure took off in the 1970s.

Norway’s fourth largest city is associated with oil well outside the country’s borders and the label has helped attract businesses and jobseekers on a large scale.

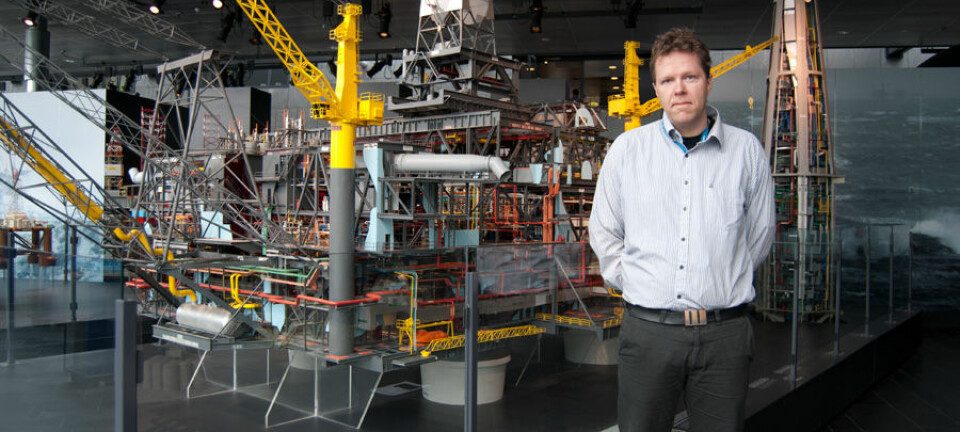

But being associated with the oil industry will cannot a positive connotation forever, reasons Erik Fossåskaret, a sociologist at the Department of Media, Culture and Social Sciences at the University of Stavanger:

“The time will come when the young people of today will be telling their grandchildren what kind of work they did,” he says.

“So it’s very likely that having been a lobbyist for opening new oil fields won’t be so popular – at least if the climate changes become as serious as many now predict.”

Viking city without Vikings?

Fossåskaret has worked with identities and identity building in his research. His work has encountered the subject of the relationship that cities have with their own histories.

“Many Norwegian cities have carried out active branding of their histories, with varying degrees of success if historical accuracy is used as a yardstick,” he says.

For instance local merchants wanted to sell the city Trondheim as a Viking city in connection with its 1000-year jubilee in 1997.

The problem was that there never were particularly many Vikings in Trondheim.

Its luck was little better with the other tags it tried: “Medieval Town” and “Pilgrim Town”.

“Stavanger has a rather special history, so we haven’t dwelled on the past in the same way,” says Fossåskaret.

Chapels don’t sell well

What do you connect with Stavanger’s history? Oil is certainly a front-runner, but the city’s older and more conservative past is predominant for many Norwegians.

“Stavanger is historically Norway’s teetotallers’ town and also the golden buckle of the country’s bible belt. Social policies regarding abstinence from alcohol and a proclivity to join Christian sects with all their different churches are a large part of its history – but this probably isn’t much of a selling point,” says Fossåskaret.

He stresses that residents might not be embarrassed by their city’s religious history, but they know it’s not a flag to wave when trying to attract conventioneers and trade fairs.

Stavanger also has an industrial history, but this isn’t used promotionally either.

“Stavanger had a large canning industry, but it had no distinct proletarian culture with an extensive class consciousness – they didn’t exuberate working class pride as they did for instance in Oslo,” explains Fossåskaret.

“The Christian notion of responsibility for one’s own life and fate led many of the poor to feel accountable for their plight – to put it bluntly it was your own fault it you were poor. This isn’t something to rejoice about today in celebratory speeches and anniversaries,” he asserts.

Renewable, in parallel with the oil

So when the oil label no longer serves a purpose – what then? Fossåskaret thinks the solution will be to look to the future.

“Now it looks like the replacement could be energy town,” he says.

“Energy is a broader concept than fossil fuel and it has a better ring to it now that people are aware of the potential dangers of the petroleum industry.”

An ambitious brand name building of the energy town Stavanger is in full force. In February the International Research Institute of Stavanger (IRIS) established the networ Renewable Stavanger.

This is a network for companies and others taking initiatives toward renewable energy. The objective is to make the region a leading arena for renewable technology, such as wind power and terrestrial heat, which can create jobs in the area.

“This is a vision for ways that Stavanger can develop in parallel with oil – not instead of oil,” says Brage W. Johansen, vice president for strategy and business development at IRIS.

“We have no illusions about out-competing oil, but as regards the tourist trade for instance this can be a good thing.”

Many banners to wave

Erik Fossåskaret also underscores that Stavanger will continue to live off oil for many years to come.

“When the big oil corporations come to town it’s clear you choose to raise the banner in the harbour that says Oil Town – that’s not a situation where you emphasize our old wooden buildings,” he says.

“But you could say that the city has lots of banners at hand for when others visit.”

Fossåskaret mentions “wooden building town”, “beach volleyball town”, “cultural capital” and “happy food town” as labels Stavanger has used on various occasions in recent years.

Space for multiple identities

The big question is whether the oil stamp is too indelibly printed to be washed out.

“It certainly won’t be all that easy to sell Renewable Stavanger when we’re competing against oil. I think this could be a challenge especially in competition for competence,” says Johansen.

“Many would opt for a handsomely paid job in the oil industry rather than a somewhat less lucrative job in the renewable energy sector.”

Johansen is nevertheless sure that the focus can be shifted over toward renewables, sooner or later.

“For the next decades the petroleum industry will be so profitable for Western Norway and Stavanger that expecting to out-compete it is of no use. But lots of projects that will be part of Renewable Stavanger are already up and running so there’s an enormous potential here – it’s a question of putting it to use rather than starting from scratch.”

“It’s a matter of an multiple identity, being multifaceted,” says Fossåskaret.

“Individuals do it; we are different persons depending on who we’re talking with or the situation we’re in, and cities can do the same thing,” he concludes.

----------------------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling