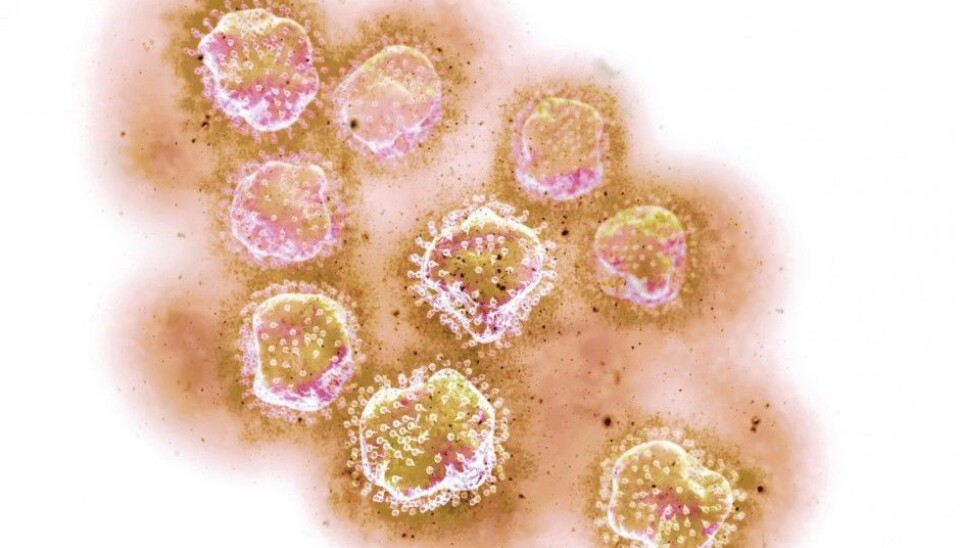

Genetic variant protects against hepatitis C

Thanks to a genetic defect, quite a few of us have a better than average chance of overcoming the liver disease hepatitis C.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

A Nordic study has shown that one in three Northern Europeans are born with a genetic variation that protects them from the potentially fatal, viral disease hepatitis C.

Scientists from Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland have studied the genes of nearly 400 individuals who were treated for hepatitis C.

They were aware that a third of the Nordic population carries a defect in the gene called ITPA.

Now they know that people with this variant benefit more from hepatitis C treatment than those without.

Tricking the virus

Thus, the variant in the gene makes it more likely that these people will fully regain their health. Even when medication kills the virus, the infection turns up again in about one-fifth of all hepatitis C patients.

But patients with the variation had five times less risk of a relapse after treatment.

The ITPA variation causes the enzyme known as ITPase to malfunction.

This enzyme “clears away” genetic building blocks which our cells are not using.

The defect version of the enzyme can not fulfill the cleaning task. This allows more unstable building blocks to circulate and be requisitioned by the hepatitis C virus.

The virus is “tricked” into using these faulty building blocks in its own gene sequences.

The scientists think this weakens the virus, causing instability and making it more susceptible to antiviral medications.

So the drugs work better.

Devising new drugs

The scientists hope this knowledge will contribute to the development of new drugs that impair the ITPase enzyme.

They definitely don’t want to knock it out completely. Experiments with animals show that they don’t survive without the enzyme. But a medicine that partially blocks its functioning for shorter periods could be effective in battling the virus, the medical researchers say.

This would be of help to the two-thirds majority of Northern Europeans who have normal functioning ITPase enzymes.

Patients with hepatitis C are currently given the drug Ribavirin. But the medicine has a lot of side effects, including the risk of foetal damage among pregnant women. The scientists hope new pharmaceutical solutions will be found that entail fewer side effects.

Protection against Ebola?

“We need to conduct further research to determine whether these genetic variations also protect against other serious viral infections,” wrote Martin Lagging, one of the scientists involved in the study, in an email to forskning.no.

Lagging is a physician and professor in clinical virology at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

He thinks that if a drug could be developed that is capable of weakening the ITPase enzyme, it theoretically could help fight other viruses, perhaps even Ebola.

Helpful defect

There are several different varieties, or genotypes, of the hepatitis C virus. Some of these can be treated more easily than others.

The Nordic scientists studied the genotypes designated as 2 and 3. Genotype 3 is the most common in Norway, but genotype 1 is the most common worldwide. So the tests that have been conducted to date do not prove a link between a patient’s enzyme types and the most widespread form of hepatitis C. Lagging says other studies indicate that deficient ITPase enzyme activity can also have a beneficial effect in fighting hepatitis C of the genotype 1 variety.

A number of elements naturally found in the body can protect against hepatitis C. Earlier this year, American scientists discovered that elevated levels of a specific protein increase resistance to the virus.

Research has also shown that other diseases are hampered by human genetic variations. One such genetic defect can protect against HIV.

--------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling