Men of the forest: What was it like to be a lumberjack?

Lumberjack attire and a full beard are today associated with hip and urban parts of modern cities. Professor of history Ingar Kaldal argues that loggers working deep in the forests back in the day, were in fact also modern, for their time.

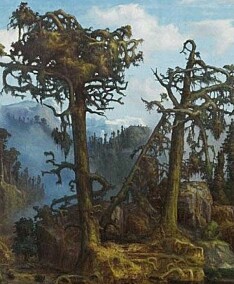

Wherever you don’t find mountains, water or cultural landscapes, Norway is forested. And the forest has been people's workplace since time immemorial. Many Norwegians likely have ancestors who made a living from it.

Nevertheless, very few of them know much about what it was like to be a lumberjack before the age of large forest machinery.

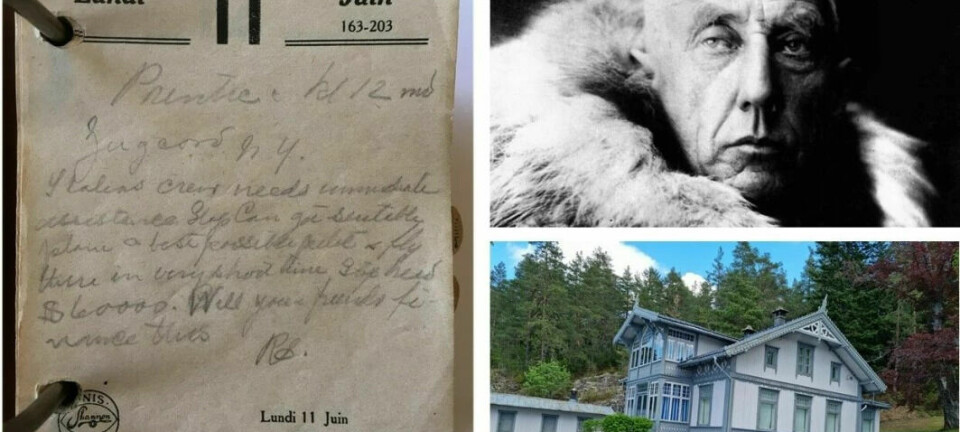

One person who has been researching this topic for several decades is Ingar Kaldal. He is a professor of history at NTNU, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, as well as an author.

Readers come to know the logging culture better through the 400-plus pages of his recent book Skogens menn: Minner og myter om hoggere og fløtere - Men of the Forest: Memories and myths about loggers and drivers. Kaldal relates the memories of the old loggers and the myths that they told each other and shared with him.

Myths were important for the culture

“When I say the word myth, people imagine falsehoods and lies,” Kaldal says.

But for him the myths have a different meaning.

“If you only had one interview with a slave from the Viking Age, you wouldn't ignore it and say it wasn't representative enough,” Kaldal said during his book launch on 27 September.

“The myths express something about logging culture through the telling. They reflect an active and thriving storytelling culture.”

Kaldal's research approach is to take the myths seriously – not as truths per se, but as an expression of the forest work culture.

A modern figure

Many people probably imagine loggers working in an occupation that is ancient, unchanged and original – until logging machines entered the scene a few decades ago and eliminated the physical work. But logging is more modern than that.

The logging and log driving profession grew significantly from the 1870s onwards, says Kaldal. Log driving is the transport of timber down waterways.

The growth of logging occurred at the same time as the rise of industry in Norway. Raw materials and their transport were in high demand.

Kaldal argues that the logger was a modern figure.

“Even if lumberjacks were poor and the work was strenuous, the work and life in the bunkhouses had features that we associate with modern times. You can be poor and modern at the same time,” he says.

“Loggers earned money in the form of wages and bought food for the hut and for the forest. Servants on farms, by comparison, worked primarily for board and lodging.”

Competition in the forest

Logging also had a competitive aspect to it, says Kaldal. The goal was to do as much work as possible and get paid as much as possible.

“Everything had to be counted and measured.”

The axe and saw were simple, old-style tools.

“On the other hand, the pay, the competition and the fact that the work depended on the market are modern work features,” Kaldal says.

Appeal for modern urbanites

Kaldal believes that today, the romantic feelings people have for loggers are perhaps strongest in cities. He hopes that the book will appeal to city dwellers with cabins in the woods.

“Being a lumberjack has appeal. You don't need to have chopped a lot of wood at the cabin to feel a bit like one,” he says.

If we go back a few years, the appeal was clearly visible in urban areas, and in the USA especially, where the term ‘lumbersexuals’ is well known.

Young men wore boots, wide braces, chequered flannel shirts and had full well-trimmed beards. However, the recreated image was not particularly authentic.

‘This fashion trend has been interpreted as a search for something masculine in a time where filling the male role was perceived as more difficult than it used to be,’ Kaldal writes.

‘Men don't drink hot cocoa’

Fitting in and fulfilling the male role was important for the loggers as well. One example can be found in the chapter entitled ‘Real forest guys – and -women.’

‘A young boy who started as a logger in Finnish Lapland once experienced that older workers, upon discovering that he was carrying a thermos of hot cocoa, promptly emptied it. ‘Men don't drink hot cocoa,’ he was told. The old fellows were even sceptical about bringing fruit as part of their lunch.’

Kaldal also talks about how cigarettes instead of pipes were unacceptable in American logging culture. Cigarettes were considered feminine – and in some cases also homosexual. Anyone who lit a cigarette could be sent home.

Had to fit in

A bunkhouse mate of the Norwegian poet and lumberjack Hans Børli once set a frying pan on the note Børli was writing a poem on.

How could small things like the wrong kind of drink, a different way of smoking tobacco and the joy of writing poetry be so poorly tolerated?

“You had to fit in and learn to cope with the crude jokes and the humour,” Kaldal says.

Kaldal wonders if may be that the most raucous stories and anecdotes were part of a ritual of sorts when new boys and men joined bunkhouse life – a test to see if they fit in.

“Being one of the guys, not being prissy and not standing out in terms of food preferences, were part of the culture. They were packed into the bunkhouses like sardines, and being oppositional, starting discussions or disagreeing couldn’t be done thoughtlessly. Yet tolerance was also important for preserving the peace in such a cramped environment," Kaldal says.

No reliable figures on how many people did forest work

Kaldal states that 5000 people are currently employed in the forest industry in Norway. A large percentage of them work in administration.

It's difficult to know how many loggers there have been over time; approximately 36 000 were estimated around 1950. It is quite conceivable that there have been more.

“The figures are difficult to trust. They’re taken from the censuses and what people reported they made a living from,” says Kaldal.

A man could be both a small farmer, a road worker, a sawmiller – and work in the woods in the winter. That was high season for loggers, because the snow made it possible to transport the timber.

“It's a bit of a guessing game if a man said he was a logger or not,” says Kaldal.

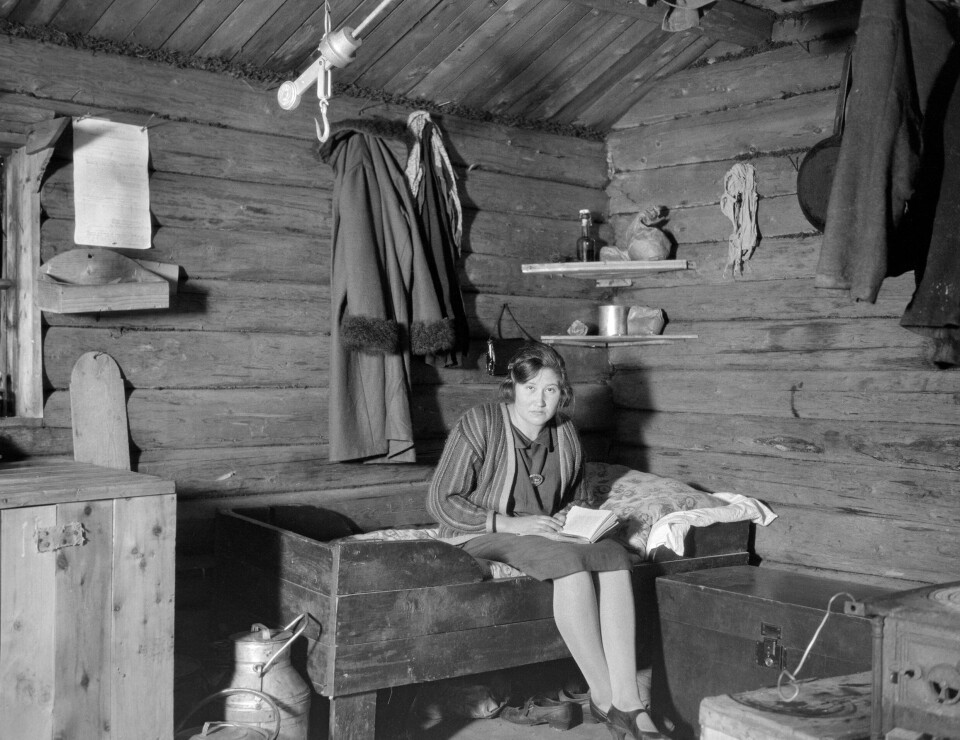

Women in the bunkhouse

Kaldal addresses gender roles in various ways throughout the book.

Lumberjacks definitely had a macho culture. Today, Norwegians might use the term guttastemning, akin to the English use of ‘brotherhood,’ a friendship like no other.

Kaldal writes that the Scandinavian bunkhouses improved somewhat over the course of the 20th century, once women came in as cooks. Being one woman among so many men was undoubtedly challenging at times.

“But it was a very transparent environment. If anyone verbally abused or otherwise harassed her, the others would hear about it. There wasn't much opportunity to cover things up,” says Kaldal.

Often she also might have been related to many of the guys.

“One of these women says she was protected, probably due to the fact that she needed it from time to time."

Female elements in a rough and tough male role?

Although fitting in was important, men’s role in the bunkhouse was perhaps somewhat different than you might intuitively think.

“Things happened in the bunkhouse that would otherwise have been seen as women’s work,” Kaldal says.

“Loggers cooked, and they had to sew and patch their clothes. But a logger's sewing box was probably quite different from his wife's at home,” says Kaldal.

So when lumberjacks cooked up some chops, it wasn’t seen as a female activity.

In the same way, the wife at home on the farm did routine work that her husband would normally do, like fixing a fence or getting a bull back that had broken out of the barn.

On the whole, the logging environment did not match the stereotypical notions of feminine and masculine.

Kaldal compares the situation to how men today often take on grilling the meat, or that cooking gourmet food does not negatively affect their gender identity. On the contrary.

Could be a guy without being strong-as-bear

Although forest living had its clear behavioural norms, you did not have to be a muscular guy to find your place.

“Even in the woods your manhood could be recognized without it being related to your physical strength,” says Kaldal.

You could compensate by tackling the rest of the work in a sensible way.

“You could be skilled and nimble at driving logs down the river. And whoever was able to manage that could become a hero.”

Audacity was fine as long as a logger didn't became foolhardy. Then you were quickly seen as someone who couldn't take care of yourself or your mates.

Nearing the end from mid-20th century on

In the 1950s and 60s, traditional logging life faded away.

“The old culture met the new era in the 1960s, as sons and daughters travelled to cities to learn occupations through books,” says Kaldal.

For men who wanted to take their sons with them into the forest to pass on their trade, reading and writing were regarded as somewhat useless. The lessons from school were seen as disconnected from reality.

Kaldal says the attitudes that logging brought with it can still be found in villages today – like when someone asks what we’re going to do with so many people holding master's degrees.

At the same time as logging jobs declined, many women took paid work in the health sector. Male identity was challenged.

Many young men were no doubt tempted to take a different path, even if it went against expectations at home. Kaldal conveys the low status that loggers held – but also what lay behind the low status.

“An important purpose of the book is to make visible a social group that hasn’t been highlighted that much,” says the author.

Enormous developments

Arne Fjeld was a logger. He and his wife, Gyda Lømo Fjeld, made the trip to Kaldal’s book launch.

Fjeld previously worked at the Norwegian Forest Museum. He still teaches school classes at the museum’s nature school where children can learn about the old wooden objects and what they were used for. Fjeld turns 80 this year and started logging when he was around age 15.

“The development has been huge. Before my time, there was just the axe. And then I experienced how logging developed from using axes to using the largest mechanical harvesters over all those years,” Fjeld said.

His grandfather was a forest owner.

“Grandfather had manual lumberjacks of the really old-fashioned type,” Fjeld remembers.

Fjeld confirms that axe handling was heavy work.

“Of course I became strong! I'm still making use of that strength,” he says.

The first chainsaws weren't exactly effortless to use, either. They weighed far more than today's chainsaws, made terrible noise – and no one thought of using hearing protection.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------