Roald Amundsen’s final journal entries were about his lover and money

The polar explorer was waiting for his lover. He was just going to write a little more polar history by saving crashed Italian polar explorers first.

Roald Amundsen's home in Svartskog village is neither large nor flashy. The house is beautifully situated by the Bunnefjord, a half hour drive from Oslo.

Anders Bache is a consultant at the home of the polar explorer, which is part of the Follo Museum. We meet him in the courtyard on a hot May day.

Sciencenorway.no has asked him to select and tell us about an exciting object in the museum.

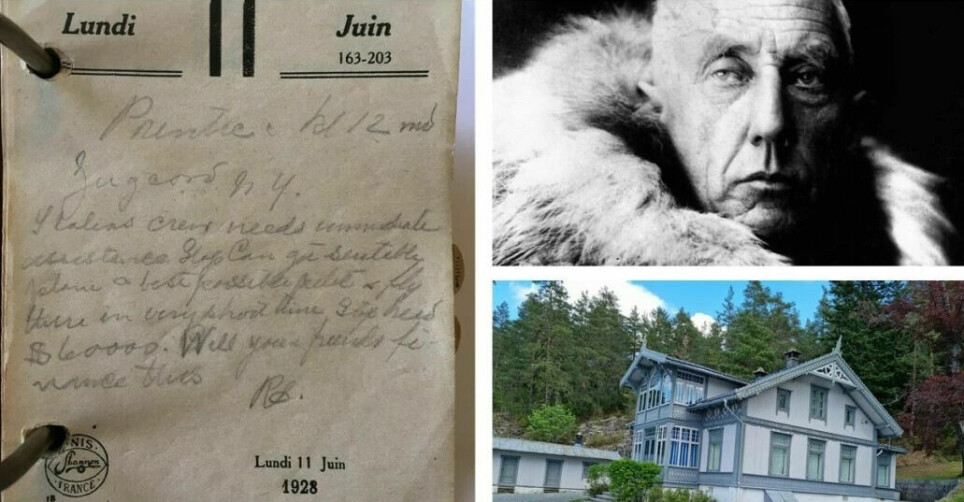

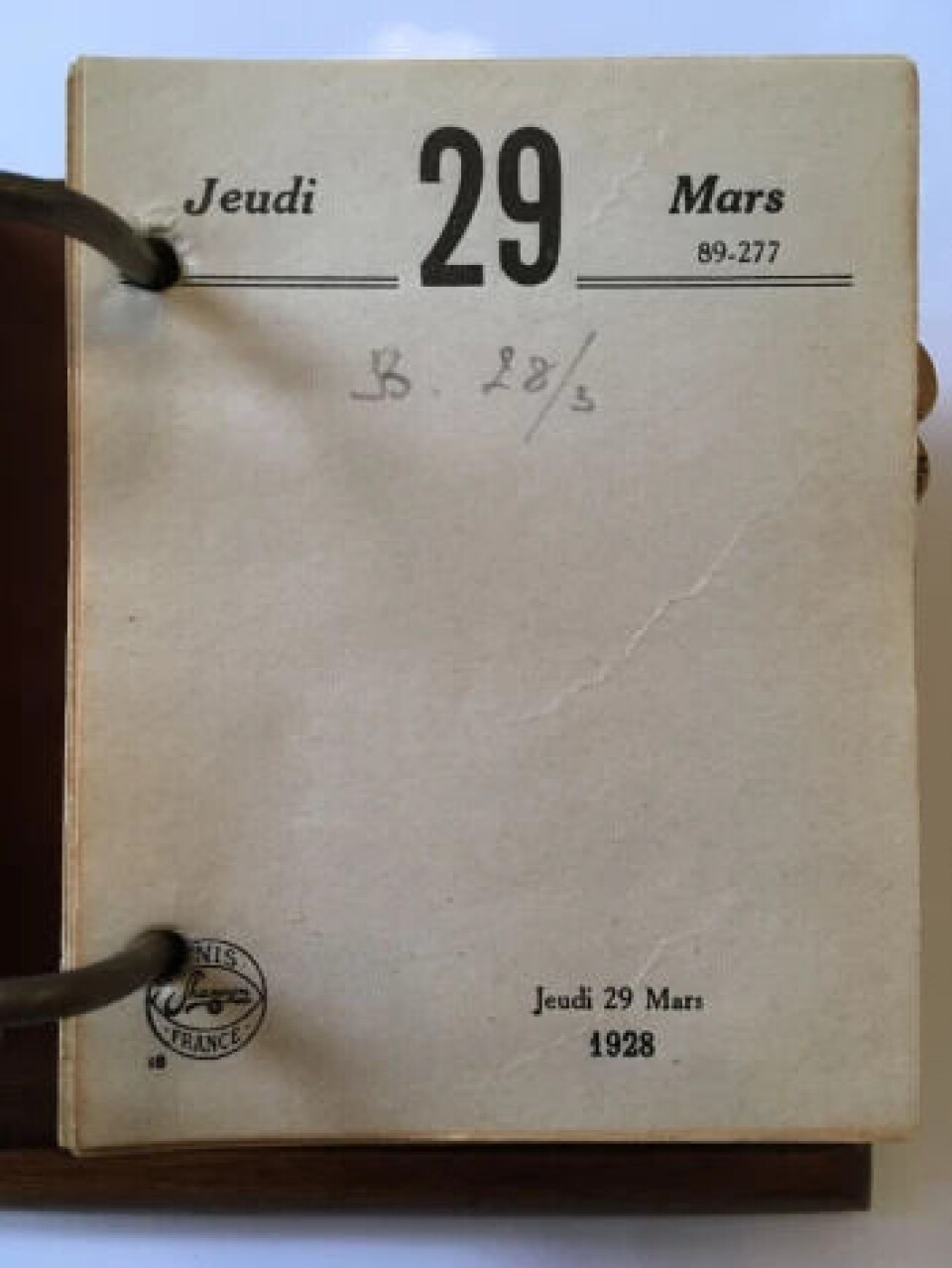

Bache has chosen Roald Amundsen's last note from the calendar on his desk, dated 11 June 1928.

Superhero and researcher

Amundsen was a superhero in his day. He was a scientist and a polar explorer. In 1903 he led the first expedition to sail through the Northwest Passage. In 1911 he led the group that first reached the South Pole. With Amundsen as commander, the airship Norge flew over the North Pole in 1926 – crossing the Arctic Ocean for the first time.

The polar explorers helped make Norway famous.

“Roald Amundsen and Fridtjof Nansen were big figures in the world, at least in western countries,” says Ulrike Spring. She is a professor of history at the University of Oslo.

In 1928, Amundsen turns 55 years old. He is bankrupt and living at his home in Svartskog.

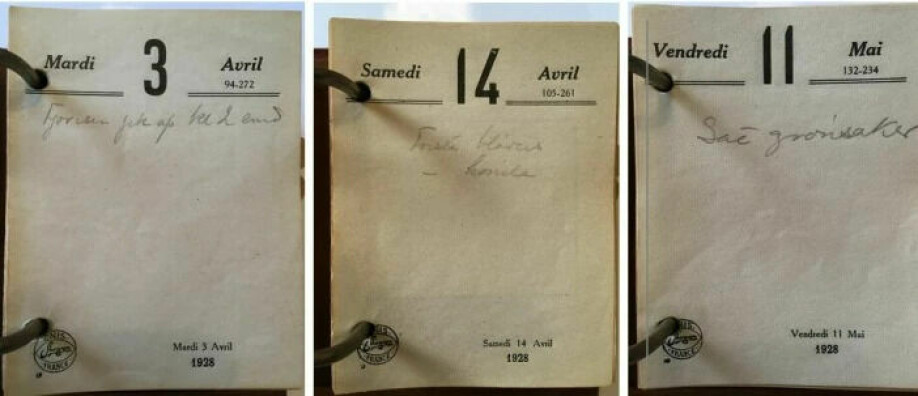

He tracks and makes notes on the natural world around him.

Fjord ice breakup at 2 pm, he notes in his desk calendar on April 3rd. The first hepatica, first bumblebee, it says for April 14th.

On May 11th, vegetables will be planted.

Scientist or adventurer?

The purpose of the expeditions to the polar regions was not just to arrive first.

“There were still a lot of areas that hadn’t been explored yet. Anything that could be collected from photographs and data was useful for understanding the geography, the ice and how the polar regions functioned and what they looked like,” Spring says.

“The polar explorers made observations and took scientific measurements. Amundsen followed in the footsteps of the ten-year-older Fridtjof Nansen – both as a polar explorer and as a researcher. But several people have claimed that Amundsen was mostly adventurer and less a scientist. This viewpoint is debated among researchers,” according to Spring.

“Amundsen had some university education, and then took some courses, while Nansen had both relevant education and worked as a researcher. It’s not fair to compare them,” says Spring.

“Research was professionalized during the 1800s. Before that time, there was little difference between professional researchers and those who simply wanted to go on adventures and discover new worlds. Gradually it became more difficult for just anyone to propose scientific research,” says Spring, who studies 19th-century and early 20th-century polar history.

“Amundsen had less interest in research than Nansen, for example. But by bringing a researcher on the Maud expedition, the trip also gained a scientific purpose and contributed a lot of interesting material,” she says.

The scientist was Harald Ulrik Sverdrup. The Maud expedition from 1918 to 1925 is considered one of the most important Arctic research expeditions of all time.

Super celebrity

Roald Amundsen was admired and adored in his time.

The explorer received public funding and was sponsored by wealthy people. He endorsed brand-name products like bicycles and bath oils. He lectured and wrote books.

“The media played an important role starting at the end of the 19th century. And they were important for Amundsen,” says Spring.

“As a celebrity, it was easier for him to raise money,” says Bache from the museum.

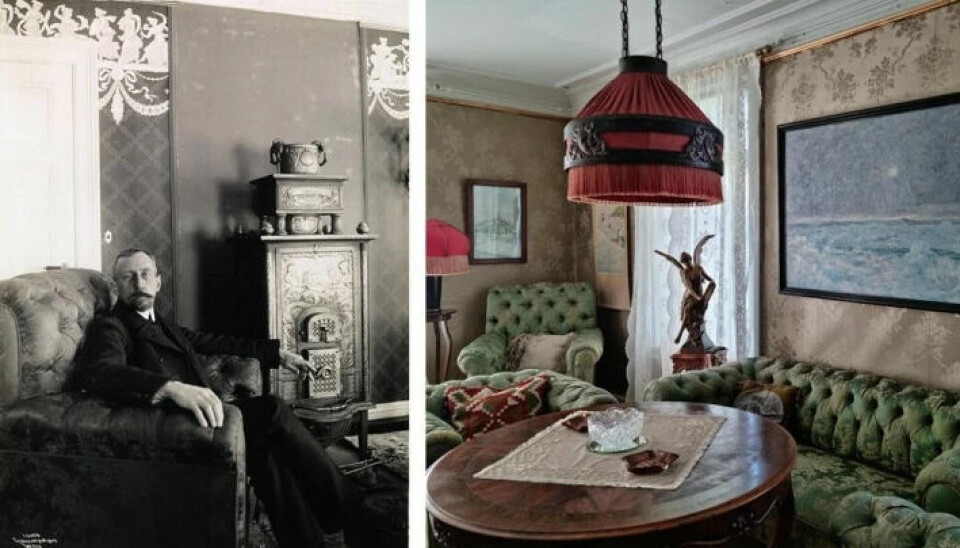

He shows us around the living spaces on the first floor. They look quite formal:

A sledge in the hallway, signed pictures of Queen Maud and King Haakon on the wall, paintings from the Arctic and Antarctic, and souvenirs from polar regions that are placed for good viewing.

But Amundsen the private person is less visible.

Storage room contained his private life

Amundsen himself was very concerned with how he appeared, according to Bache.

“He donated equipment to the Ski Museum, and he carefully chose what should be displayed in his house. Then he hid his private life in a small room: cowboy magazines, romantic novels and love letters. He didn’t want these items to appear in public,” says Bache.

He leads the way up the stairs to the second floor.

“In the workroom, we get closer to the person Amundsen was,” says Bache.

The room has a fabulous view of the fjord. And there is the desk, just the way it was when Amundsen left it in June 1928. And the desk calendar that Bache finds so exciting.

A stream of letters came to the house at Svartskog, from kings and presidents, but also from widows who sought contact with the bachelor, and children who wanted to become polar explorers. Amundsen answered many of them.

He also received visitors at Svartskog.

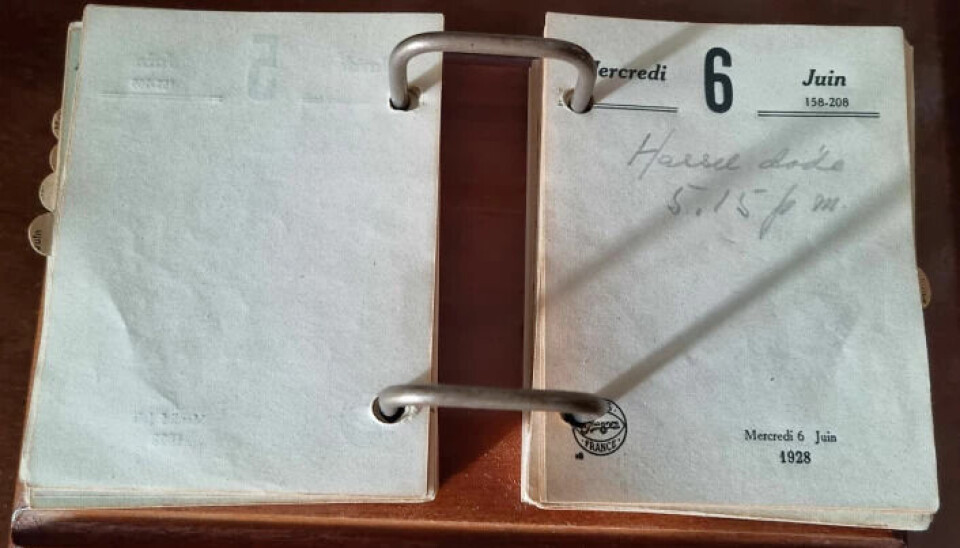

‘Hassel died at 5:15 pm,’ he wrote on June 6th.

The sober words belie a dramatic story. His friend and polar explorer Sverre Hassel had come to visit after a stay in hospital due to heart problems.

“When Hassel came to Svartskog, he felt a pinching in his chest. Suddenly he fell over dead in the garden,” Bache says.

After Amundsen's death, the family protected his privacy, according to the consultant.

Secret women

“The polar explorer façade and the hero story were made available to the public. Everything else was swept under the rug and kept private. Everything that made him an ordinary person, like his love stories, wasn’t talked about. His women were secret,” says Bache.

Amundsen kept journals of various types. On the polar expeditions he kept a logbook with page after page about the weather and the ice. He also had a private diary, addressed to Kiss.

Kiss’ real name was Kristine Elisabeth Gudde Bennett. She was married with two children. Amundsen and Bennett wrote letters and visited each other. Amundsen writes in the diary that he longs for her, he’s in love, he’s jealous, he sleeps on the pillowcases she sewed for him, he uses her handkerchiefs.

Eventually, the relationship turned into a friendship. The letters have disappeared, but the diary survived and ended up at the National Library of Norway. The contents have been kept secret for 50 years. The diary has now been digitized and will be published as a book later this year.

Amundsen's last lover, Elizabeth Magids, called Bess, was also married and secret.

Contact with B.

Bess divorced her husband in Canada and left for Norway.

Roald Amundsen's last diary is still on his desk. This is the item that Bache finds so exciting.

In the spring of 1928, Amundsen is waiting for Bess to arrive. They are still in contact with each other.

On some days the letter ‘B’ is the only thing noted in the calendar.

“These are probably the days he was in touch with Bess,” says Bache.

They call and telegraph. The phone bill testifies to the contact between Bess and Roald.

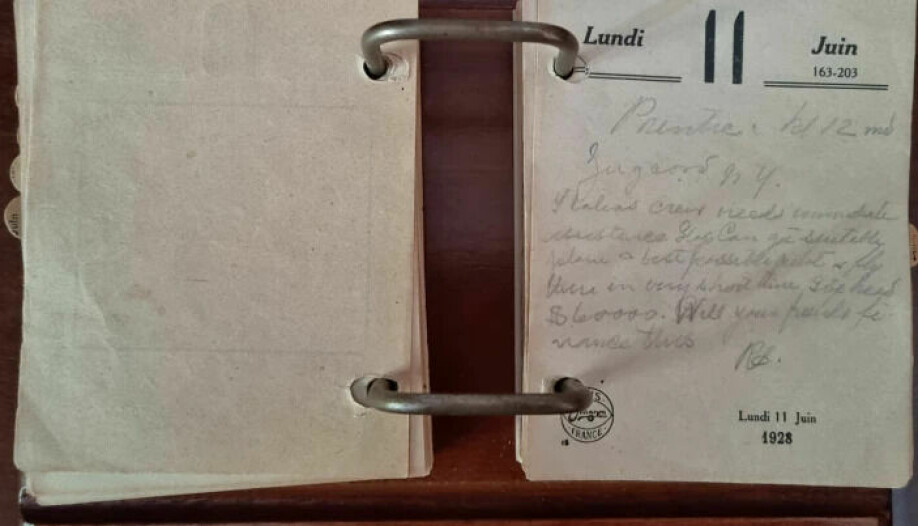

On June 11th, Amundsen makes his last note in the calendar.

Italians in need

The note is about raising money.

During these days in June, Amundsen is planning a new expedition.

The Italian Umberto Nobile was on the airship Norge that soared over the North Pole in 1926 – one of Amundsen's most famous achievements. Now Nobile had travelled to the North Pole on a new airship. The expedition was supported by the Italian government and included research assignments along the way. But Nobile and his crew crashed in bad weather and lost contact with the outside world.

All polar expeditions at this time received a lot of attention. The news of the crash landing of the airship Italia spread around the world. Hundreds of people go to look for the explorers. Amundsen wants to go, too.

He makes several attempts at organizing an expedition. The Norwegian government holds back, because the Italian dictator Benito Mussollini does not want a Norwegian rescue expedition. Mussolini is particularly skeptical of Amundsen, who he believes took too much of the credit for the previous expedition.

Amundsen can’t afford to pay for the trip himself. His expeditions were expensive.

Now he hopes the wealthy American Lincoln Ellsworth will donate $ 60 000 to the rescue operation.

The final note

Amundsen drafts a telegram on 11 June 1928:

Prentice. 12 noon. Jugcord N4, Italy's crew needs immediate assistance. Stop. Can get suitable plane and best possible pilot & fly there in very short time. Stop. I need $ 60 000. Will your friends finance this. RA

But he gets a ‘no’ on this attempt as well. Norwegian newspapers print the news that the famous polar explorer will be staying home.

Three days later, the phone on his desk rings. The call is from a Norwegian businessman in Paris. He can provide Amundsen with a French plane.

“Some people believe that Amundsen wants to travel to be a hero again by saving Nobile, but perhaps he felt some responsibility. He had lived all his life on the ice, and he couldn’t bear to sit at home while people suffered. Then suddenly the phone rings on June 14th. He can’t say no, but this is the beginning of the end,” says Bache.

Two days later, the French land in Bergen. The next morning, Amundsen and Leiv Dietrichson arrive by train.

Amundsen's journey generates a lot of attention. Journalists follow him all the way from Oslo to Bergen and to the pier where the seaplane is located.

Final trip

He tells Bergens Tidende newspaper that the potato field at Svartskog will have to wait. Now his new chapter in life as a polar explorer is going to be written.

Thousands of people have gathered to wave goodbye to the plane that first heads to Tromsø. Many people have also turned up there to celebrate Amundsen.

On June 18th the plane departs Tromsø. Three hours later, all contact ceases. Amundsen and the five others on board have disappeared.

His lover Bess comes to Svartskog only a few weeks after Amundsen sets off towards the North Pole. Her wait for him to come home is in vain.

Amundsen is gone for good. No new notes are added to the calendar at Svartskog.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no