This may be the reason why ultra-processed foods make us eat more

A lack of protein in ultra-processed food might be one of the drivers of the obesity epidemic, according to researchers.

Interestingly, it all started with insects.

More than 40 years ago, entomologist Stephen Simpson from the University of Oxford was working on his PhD project. He experimented with grasshoppers to find answers to a basic biological question: What controls appetite – in other words, what and how much we eat?

What mechanisms enable animals to choose a balanced diet, so that they cover their need for various nutrients?

The results of the study showed that the grasshoppers were not hungry for just any source of calories. Their appetite for different nutrients like fat, carbohydrates and salt competed with each other. But the need that always seemed to be the strongest was the hunger for protein.

In other words, the grasshoppers continued to eat until they met their need for protein, even if this meant that they were consuming more than they needed of other substances.

But did this only apply to grasshoppers?

Or could this hunger for protein be a fundamental mechanism governing food choice in other species – and perhaps even in humans?

Can’t store proteins

Physiologically, this function could make sense.

Proteins are absolutely necessary as building blocks in our cells and for the body to function. At the same time, we have no way of storing proteins, like we can with fats and carbohydrates. We are thus dependent on a steady supply of proteins through food.

Around the turn of the millennium, Simpson conducted studies of several animals to find out more. And in 2005, he and his collaborator David Raubenheimer put forward a new hypothesis that they termed the protein leverage hypothesis.

Their hypothesis did not only state that a number of species, including humans, control their food intake according to the proportion of protein in their food. The hypothesis also suggested that this mechanism might be one of the fundamental causes of the obesity epidemic.

Overeating to get enough protein

The idea behind the hypothesis is that the body is designed to absorb a certain amount of protein from food.

It’s not that we need to cram in as much protein as possible. On the contrary, a lot of research suggests that too much protein is linked to poorer health and a shorter life. On the other hand, consuming too little protein is detrimental.

Therefore, the body probably keeps pretty close control over how much protein we eat and has an efficient mechanism to get us to consume what we need.

Simpson and Raubenheim argue that when the protein content of food is low, we remain hungry for more food until the need for protein is satisfied.

The need for proteins thus trumps the regulation of other nutrients.

So if our diet is low in protein, we will continue to eat until we have enough protein, even if that means we overeat other nutrients. And trouble lurks when those other nutrients are fats and carbohydrates.

Ultra-processed food – a trap?

This, the researchers believe, is where western ultra-processed food comes in.

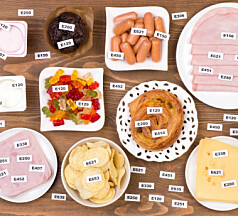

Heavily processed food is often low in protein, but contains all the more fat, sugar and easily digestible starch. Various additives and flavour enhancers like the “meaty” flavour of umami are also often added to make the products more tempting.

In this way, ultra-processed food becomes a trap for us. The products are made so irresistible that they trick us into choosing them instead of foods with a higher protein content, as we would normally do.

But the need for proteins remains a strong force in the background. It drives us to eat more to satisfy our hunger for protein. Then we end up eating more fat and carbohydrates than we need, Simpson and Raubenheimer believe.

They argue that the drastic increase in overweight and obesity in recent decades could be due precisely to the unfortunate encounter between our increasingly ultra-processed diet and old biological mechanisms to ensure the body gets enough protein.

Many new studies

When the two insect researchers came up with their hypothesis in 2005, many nutritionists were sceptical that this idea could be relevant for humans.

But many more studies have been done since then.

Numerous surveys have confirmed that a separate appetite for proteins exists that most species probably have. And in some species, including humans, this appetite for protein wins over the urge to eat other nutrients.

Studies on people indicate that the intake of proteins remains surprisingly constant, both over time and in different population groups.

A study from 2020 showed, for example, that the proportion of protein in the diet was around 16 per cent, both in different populations in the USA and in a number of different countries. The same did not apply to fats and carbohydrates.

This suggests that our bodies actually have a fairly precise regulatory mechanism for proteins in the diet.

Consuming more low-protein foods

Experiments have also shown that people actually tend to overeat when the protein content is low. In a study from 2011, the researchers tested what happened when people were allowed to eat as much as they wanted of food with varying protein content.

The results showed that people who were given food with only 10 per cent protein ate more than when the level was 15 or 25 per cent, mostly in the form of snacks between meals.

Another experiment that points in the same direction is a famous study by researcher Kevin Hall from 2019. He and his colleagues had volunteers eat as much as they wanted of food that was either ultra-processed or minimally processed.

The results showed that both groups consumed the same amount of protein. But individuals who lived on ultra-processed food ate approximately 500 more calories a day. This finding might align with the idea that we continue to eat until our protein needs are met.

However, other studies do not have such clear results. An experiment from 2013, for example, showed that people eat less when they consume high protein food. But extremely low protein foods did not make people eat more.

More comfort food

Observational studies have also been carried out, where the researchers look at data on what people actually eat.

The results of one such study recently showed what the protein leverage hypothesis predicts: the lower the proportion of protein people had in their diet, the more calories they consumed.

The study also showed that participants who ate little protein during the first meal of the day consumed more food in their meals throughout the day, compared to those who ate a lot of protein for breakfast. Those who started with a protein-rich meal, by comparison, ate way fewer calories during the day.

When breakfast contained less protein than recommended, people ate more convenience foods, such as cakes and snacks and fewer healthy foods such as whole grains, fruit, vegetables and meat. In other words, they chose precisely food where proteins were diluted by fat and carbohydrates.

A 2020 survey among children showed the same tendencies.

Little protein and a lot of carbohydrates were worst and best

But wait. Hasn't other research shown the exact opposite?

Studies on population groups with particularly low levels of obesity and lifestyle diseases, for example from Okinawa in Japan, have shown that the population lives on a low-protein diet.

The typical diet in so-called blue zones, where people live longest, usually consists of around 10 per cent protein.

However, Simpson and Raubenheim believe there is a very good explanation for this.

In the diet of these populations, the proteins are not diluted with fat, sugar and easily digestible starch, but with complex carbohydrates and fibre that digest more slowly. Eating a lot of this type of food does not include a large amount of excess calories and does not have the same adverse effect on the body.

On the contrary, several studies indicate that a diet with less protein and a lot of complex carbohydrates and fibre is particularly good for our health.

In a 2021 study on mice, the intriguing find was that a diet with little protein and a lot of carbohydrates was both the most harmful and the most health-promoting. If the carbohydrates consisted of glucose and fructose, the mice suffered from very poor health. If they consisted of complex carbohydrates, the mice had the best health of all.

Could be one explanation for obesity epidemic

Simpson and Raubenheim point out that the proportion of protein in the American diet has declined in recent decades, in line with the growing obesity epidemic. They believe the protein leverage hypothesis could be the explanation for this.

Hall supported the researchers’ hypothesis in 2019. He had made calculations about the weight and diet of Americans and concluded that the decrease in the protein content of food could be behind a significant part of the weight increase in the population.

Although it is unlikely that the hypothesis is the entire explanation for the obesity epidemic, this mechanism may play an important role that should not be overlooked, Hall writes in the scientific journal Obesity.

Not all data is in agreement

But the matter is not simple.

Figures on the food supply in Norway, for example, show that unlike in the USA, the proportion of protein in the diet has increased since the 1970s.

This data clearly does not align with the protein hypothesis. Nor do all the results from experiments with dietary proteins.

It is also true that the body’s regulatory mechanisms and the biological effects of various foods are connected through extremely complex interactions, which can be surprisingly different from person to person.

A lot more research thus needs to be done before we know what role the protein leverage hypothesis plays in humans, Hall writes in 2019.

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no