Norway’s constitution in the nick of time

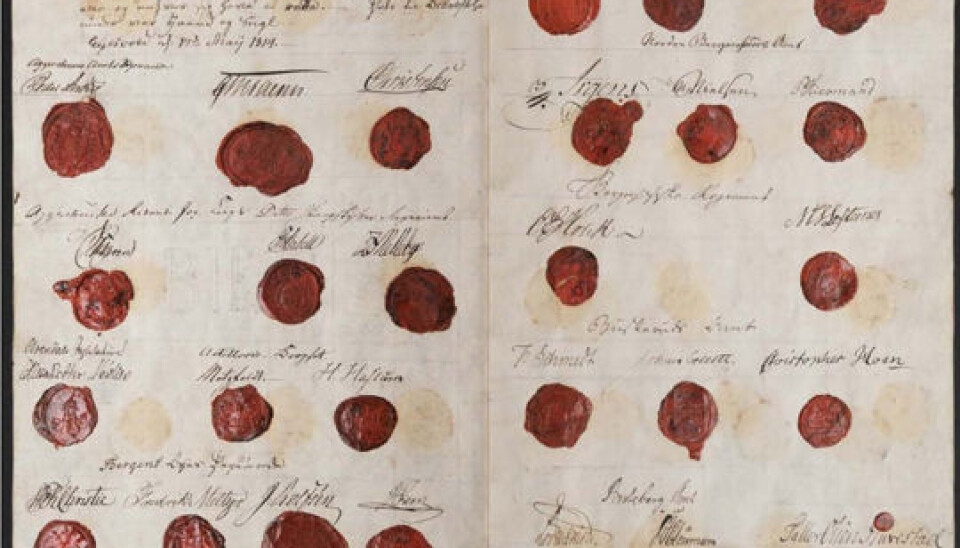

Norway is the only country in Europe with a constitution that has survived since the ground-breaking years around 1800. It was passed at the tail end of a revolutionary era, two centuries ago this year.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The passage of a constitution entails the transformation of a society.

The constitutions ratified in Europe and the United States in the years on either side of 1800 altered their countries dramatically, at least in a political sense.

Norway’s constitution from 1814 and other constitutions passed in Europe between 1789 and 1814 were all revolutionary in one way or another.

The revolutions in the USA (1776) and France (1789) paved the way. Liberal reforms in England did too.

“Norway’s independence resulted from the end of the Napoleonic Wars,” says Ola Mestad, a law professor at the University of Oslo.

“By 1814, Europe’s revolutionary period was over. Napoleon had been subdued for the time being and in the struggle between the sovereigns and the peoples of Europe, power returned to the royalty,” Mestad says.

Research on the Constitution

In conjunction with Professor Dag Michaelsen, Mestad has headed a group of researchers over the past two years who delved into this exciting period during a stint at the Centre for Advanced Study (CAS) at the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters in Oslo.

Moderately revolutionary

The articles of law in Norway’s Constitution of May 17th 1814 were not that extraordinary.

“Compared to many other new constitutions that were passed in the years 1787 to 1814, Norway’s can be characterised as ‘moderately revolutionary,’” says Mestad.

“Nevertheless, Norway’s constitution is definitely revolutionary in light of how the world looked in the 1700s,” he said.

“Recall that by the spring of 1814, the revolutionary era that was centred on the American and French revolutions was on its last legs. The Eidsvoll men had seen things get out of hand in France. They wished to change Norway dramatically but they wanted to avoid a repetition of the French ‘excesses’,” he said.

What makes Norway’s Constitution of 1814 so special is that in two centuries it has never been repealed.

All of the 100 or so constitutions passed in Europe during these revolutionary years were nullified. Only Norway and the USA’s revolutionary constitutions have survived more or less intact.

“The Eidsvoll men were well acquainted with the approaches used in earlier constitutions and consciously cherry-picked from them. Their choices proved to be even smarter than they realized,” says Ola Mestad.

Challenging the king’s veto

Most importantly, the 112 Eidsvoll men – especially the 26 lawyers among them who formulated the legal wording – chose a fortutious solution for the division of power between the national assembly (the Storting) and the king who soon afterwards became Sweden and Norway’s King Karl Johan. Although the drafters of the constitution were not aware of the significance at the time, the move opened access to a democratic parliamentary system in Norway.

Norway’s new constitution allowed the king to veto a law only twice (during the course of two consecutive four-year Storting sessions). Any third attempt by the monarch to veto that law would be squelched.

“There was nothing overtly remarkable about this when the Eidsvoll men passed it. They consciously wished to give legislative powers to the people,” Mestad said.

“But they were not aware that this would lead to parliamentarism and today’s democracy. The king’s lack of a veto power in constitutional affairs is what made Norway’s constitution so modern and in time would give the Norwegian people the upper hand with regard to the king in Stockholm,” he says.

Constitution of 4 November 1814

The Constitution passed at Eidsvoll was rather unspecific and loosely expressed.

This too would prove to be a shrewd approach.

The leeway made it possible to reinterpret the Constitution in keeping with the times.

Strictly speaking, the Constitution that was passed at Eidsvoll on 17th of May 1814 is not the one that has survived all the way through the 1800s. Very soon, on 4 November 1814, the Storting voted for amendments to the six-month old Constitution.

It would be these revisions – tailored to the newly established union with Sweden – that ensured that Norway’s Constitution survived.

In connection with the 4 November 1814 amendments, Norway was allowed to establish its own national bank – Norges Bank. It also could mint and print its own currency and above all the Storting voted that the “Norwegian language” was to continue being used in the Constitution and in government documents. The “Norwegian” referred to was actually Danish, as Norway had just spent 400 years under Danish rule.

This Norwegian Constitution of 4 November 1814 prevailed through most of the 19th century.

How could the people take power?

What was it that enabled the populace to seize the right to rule after kings and royal officials had held power for centuries?

“Today we think it self-evident that power in our country should emerge from the people. This was no matter of course 200 years ago, following centuries of hereditary rule and sovereigns who enjoyed ‘God-vested authority,’” explains Mestad.

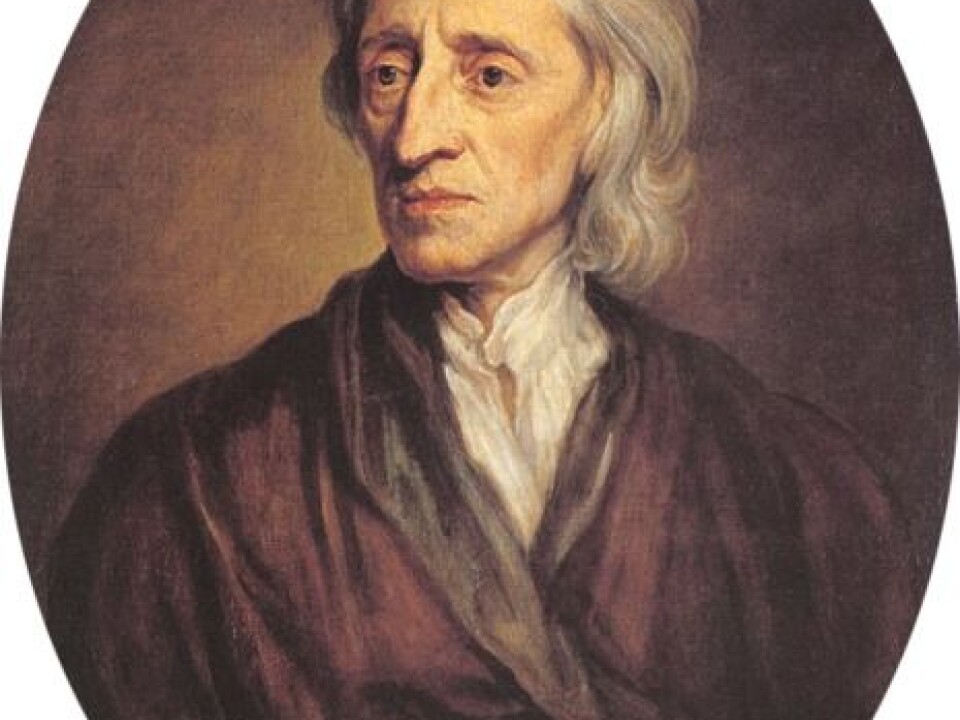

“When power in Europe came into play at the end of the 1700s, it was inspired by the revolution in the USA, and largely by philosophers like John Locke. Locke asserted that the legitimacy of the state should arise from the will of the people. The people have the right to rebel if the state fails to fulfil its social contract with them and protect ‘life, health, liberty or possessions’,” he said.

Mestad explained that Jean-Jacques Rousseau followed up by asserting that the people can always take back the power they have delegated to their leaders. This, he says, was really revolutionary in the 1700s.

“But in Denmark-Norway there had also been a notion that the power of absolute rule was given by the people. This would prove to be important in 1814,” he said.

Thrilling age

“Europe was very complex at the end of the 1700s. Take Germany, for example, which had not yet been consolidated and consisted of a patchwork of small countries. In its wars to conquer and civilise its foes, France had tried to establish the Napoleonic Code across large areas of Europe,” Mestad said.

He noted that Europe was a place where treaties marked networks of alliances and coalitions between states and principalities. And because Denmark had supported France, the losing party in the Napoleonic Wars, the Danes had to relinquish control of Norway in the spring of 1814.

A secret treaty specified that if Sweden helped defeat Napoleon, the great powers of Great Britain, Russia and Austria would give Norway to Sweden. This was compensation for Russia taking over Finland, which had been under Swedish rule.

Much remains unknown

“All in all this was a fascinating era. But still we don’t know enough about what really happened,” he says.

This is particularly true for the legal issues which arose in connection with the dramatic changes in Europe from the late 1700s to 1814.

This was a time when the ancient regimes and systems were on a collision course with the new thinkers who advocated change, who wished to usher in an era where the people were sovereign, not the royalty.

Two-hundred-year-old contemporary records from the British Parliament mention intense discussions on whether letting Sweden take over Norway was in keeping with international law. Many people were obviously concerned about these issues in the early 1800s, particularly lawyers.

-----------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling