Norwegian industry complied with German war efforts

Seventy-three years ago, on 9 April 1940, Nazi Germany attacked and occupied Norway. The Germans needed aluminium to win the war. But rather than resist their German occupiers, Norwegian industry leaders chose to cooperate instead.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Norwegian WWII stories are mostly characterized by conflicts between resolute resistance leaders and hundreds of thousands of German troops.

But less well known is the compliant role played by major industrial interests, including the light metal industry – a topic that has been studied by Hans Otto Frøland, a history professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

“This is a case where Norwegian companies worked for the Germans, as collaborators, without ideologically having a Nazi orientation,” says Frøland.

“The companies simply continued to operate on the basis of commercial, competitive interests. But by doing so they were actively aiding Germany in its efforts to win the war.”

Keeping the wheels turning

On 9 April 1940 the Germans marched right into Oslo and King Haakon VII and the Government fled to the UK. The new authorities wanted to keep the Norwegian economy going, despite the enemy occupation. Norway was dependent on imports of food and other resources.

The situation posed a difficult paradox. While hopelessly outnumbered and poorly equipped Norwegian Army units were still battling Germans sporadically early in the summer of 1940, domestic plans were being made to increase production of what the Germans needed most – aluminium.

“The war had to be won in the air. Victory in the skies required aircraft, and to manufacture planes you need aluminium,” explains Frøland.

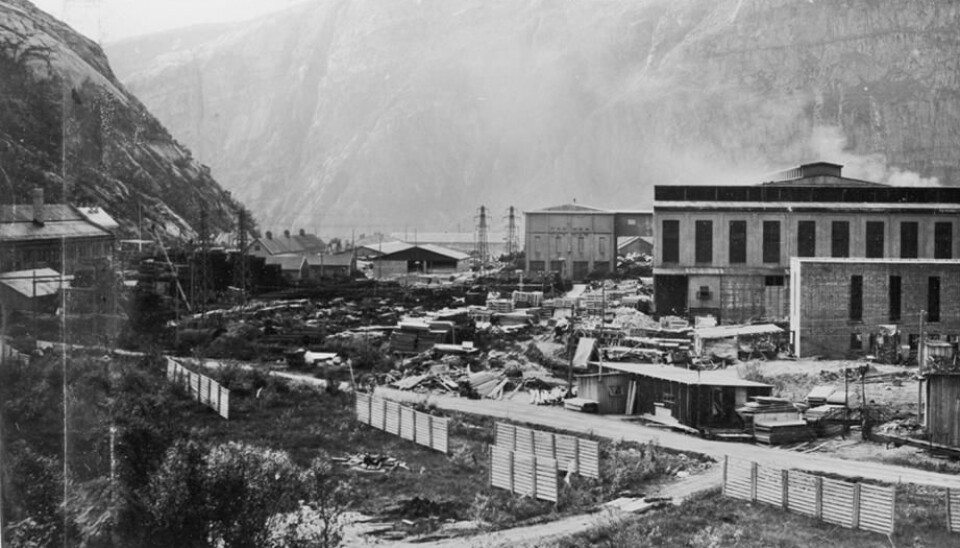

Norway is well-suited to producing aluminium, because the industrial process requires lots of electricity, and the country has oodles of hydropower. But Norway lacks aluminium ore, a mix of minerals called bauxite.

Bauxite is first processed into aluminium oxide, or alumina, and then into the metal.

A plan to increase production sevenfold

Already by May 1940, a provisional regime in Norway supported the construction of a new aluminium plant to protect this vital export industry. It would be a cooperative effort between Norwegian Aluminium Company (NACO) and Norwegian Hydro.

Almost immediately after the occupation, these two enterprises supported collaboration with the occupying forces to expand Norwegian aluminium production. Frøland says that NACO did this to maintain their solid position, whereas Hydro got involved to get a foothold in the industry.

Thus by 1941, just months after attacking Norway, the Germans had a viable strategy for increasing Norwegian aluminium production sevenfold. That would make Norway the major European supplier to the German aircraft industry.

“There were no Nazis in the management of these corporations. This was pure economic strategy. Both wanted to position themselves for the future. They didn’t know how long the war would last and it was quite possible that it would result in a new Europe, with Germany in the driver’s seat once the war ended,” says Frøland.

A failure, but not because of Norwegian industrial leaders

After Hitler’s initial victories the war started to turn, and the Germans, Hydro and NACO encountered major problems getting bauxite as the battles in Europe raged. The new factories never produced a single gram of light metal.

But the kingpins of Norwegian industry can’t take any credit for that.

“What happened in Norway in 1940 was that an occupying power came into a country and took it by force. You would have to be ideologically attuned to them to consider this okay. And it would be hard even then. Nevertheless, Norwegian businessmen chose to make use of the opportunity to position themselves commercially,” points out Frøland.

“Maybe they hadn’t given the matter full consideration, but they were drawn into a situation where they were aiding the enemy.”

Frøland stresses that the same choices were faced by lots of companies at the start of the war. Companies had to choose between bankruptcy, with the consequences that would have on the business and its employees, or cooperating with the Germans.

“This says something about how even today it can be easy for an occupying power to find partners to cooperate with in an occupied country. The dominant perception of the Second World War is that it was full of black-and-white choices, with bad guys and good guys. Those of us who study the war want to change this simplistic perception,” he says.

------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling