People often have mysterious dreams before they die

Many people experience characteristic dreams and visions in the weeks and days before life ends. It is high time we recognize the importance of such experiences, says one researcher. Several Norwegian researchers agree.

Old age. Cancer. A rare disease of the nervous system.

Whatever the reason, the fact remains: A life is about to run out. Sometime in the next few days or weeks, death will be a fact.

It is during this period that something special may happen.

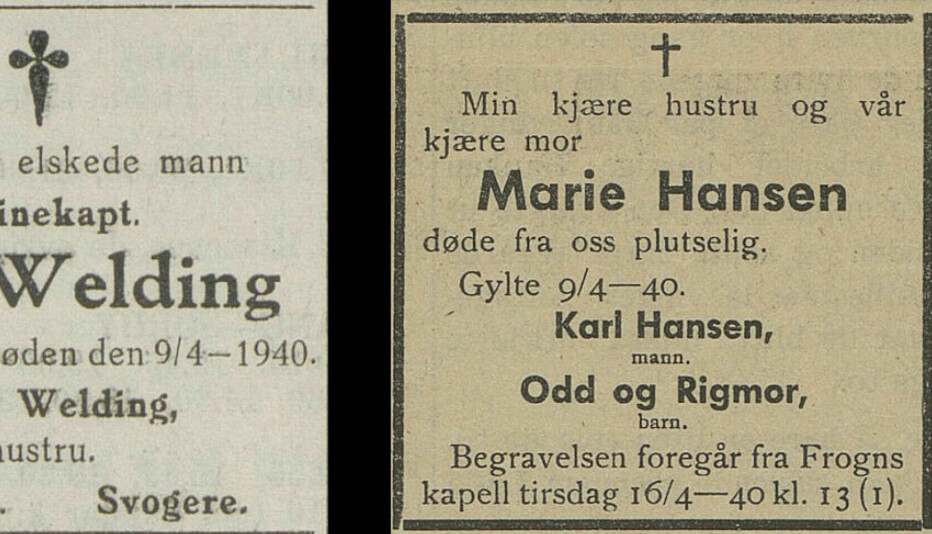

The dying person may wake up one morning having had the most vivid dream. As if it were real. The person met his or her long-deceased mother, or a dear friend who had to give in to illness a few years ago. Or a child who died far too soon.

The dying person might not even have been asleep. Rather, the strange visions arose in broad daylight, in the middle of being visited by living loved ones or the nurse stopping by to check in.

Regardless of the circumstances, the experience was more than likely positive and meaningful. The encounter might have been about love. Or about an ending, reconciliation or forgiveness for something that had gnawed at the patient for a long time.

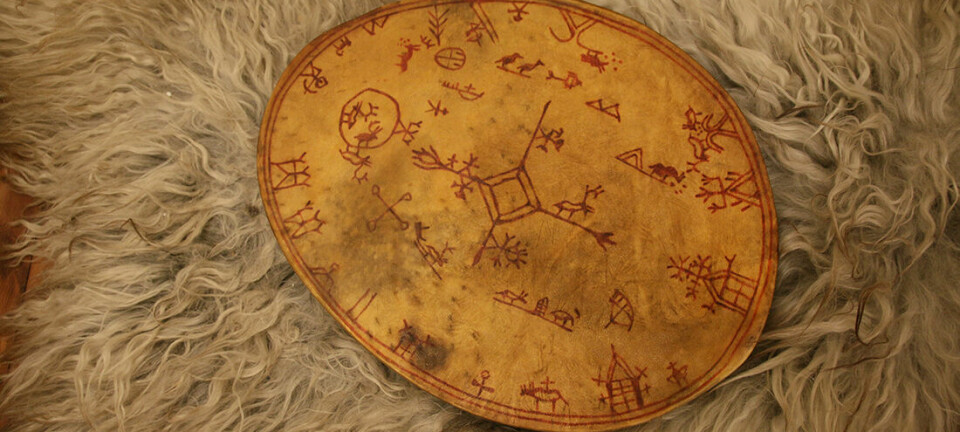

End-of-life visions and dreams have been reported by the dying and their relatives for centuries. They have floated through folk cultures as rumours and tall tales.

But recently, something new has been happening.

End-of-life dreams have entered the world of science.

From Japan to Moldova

In recent times, the phenomenon has been documented in several different cultures.

Researchers from Japan, for example, sent a survey to the relatives of cancer patients who had died. Over 20 per cent of the family members knew that the deceased had experienced special dreams or visions before death.

A study among relatives in India showed that 30 per cent reported such experiences. And the figure was almost 40 per cent in a survey from Moldova.

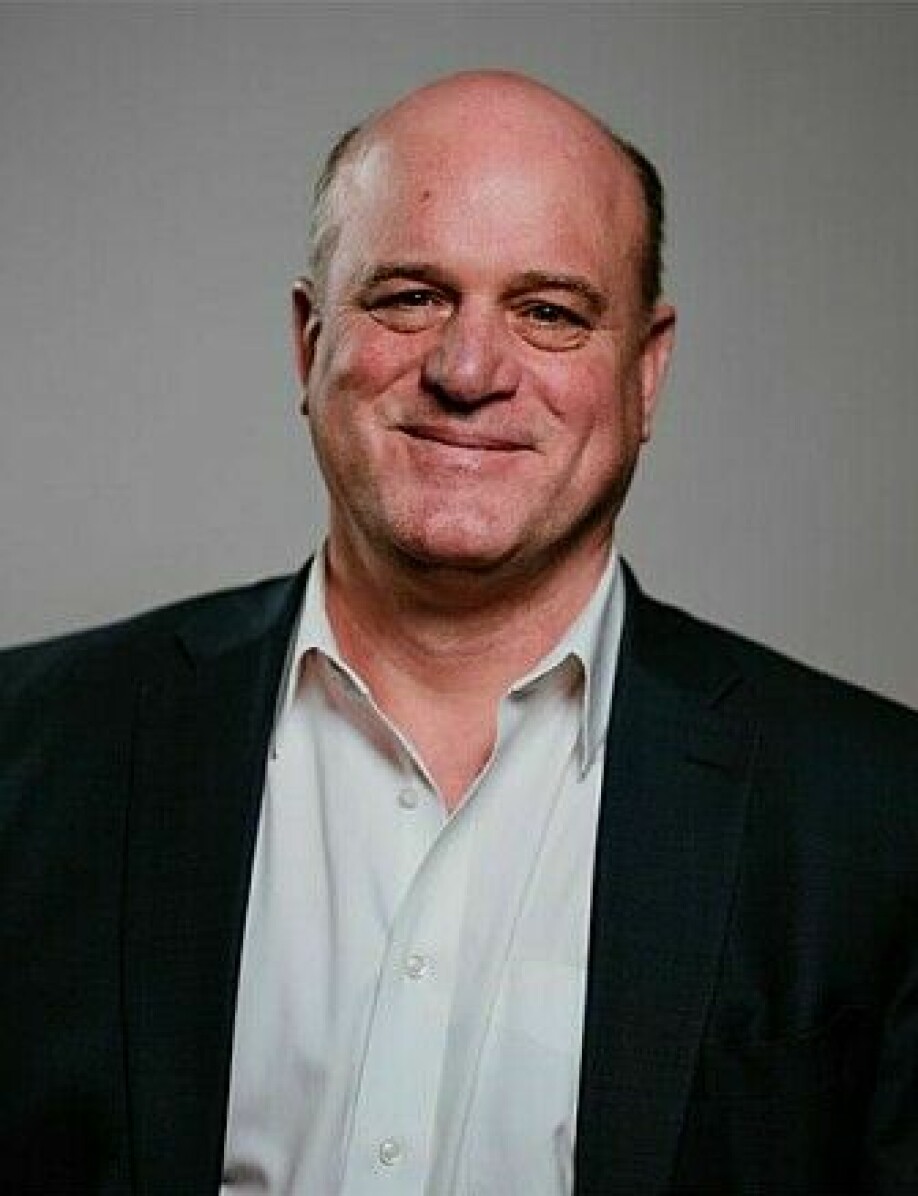

One person who has delved deeply into pre-death dreams is Christopher Kerr from Hospice & Palliative Care Buffalo in the USA.

Death as the enemy

Hospice is a place for people whose death is imminent.

The aim of health personnel who work there is not to save lives. Instead, they soothe, support and comfort patients on the way to life’s end.

As a young cardiologist, Christopher Kerr applied for a weekend job at Hospice Buffalo. His reflex was to fight death, by any and all means.

“Like many physicians, I’d never considered that there might be more to death than an enemy to be fought,” Kerr writes in his book Death Is But a Dream, published in 2020.

However, the meeting with Hospice Buffalo was to change the young doctor's view of both death and the value of what happens in a time when all hope is really gone.

An invisible infant

Kerr's curiosity about dreams and visions before death was aroused by a very special event.

One of Kerr's first patients at Hospice Buffalo was 72-year-old Mary. One day the young doctor was present while the family was gathered to spend time with the ill woman.

Then, without further ado, Mary began to rock an invisible baby in her arms, Kerr writes in the book.

She kissed and stroked the infant, whom she called Danny, and seemed extremely peaceful and full of happiness.

However, the spectators didn’t understand a thing. Was this a hallucination? A reaction to medication? No one knew of any child named Danny.

Not until Mary's sister arrived the next day was the mystery solved. She was able to relate that this was the name of a stillborn child that Mary had had before her other children were born. She had been very distressed by this incident, but never told her family about it.

No one asked the patients

For Kerr, it soon became clear that the incident at Mary's hospital bed was not unique at all. On the contrary, the staff at the hospice shared that many of their patients had special dreams and visions in the time before their death.

Eventually, Kerr met a number of dying people who had these experiences.

His interest was aroused. What exactly were these strange events, which in many cases had deep, existential meaning for the patients? And why was nothing mentioned about this in the textbooks?

Kerr began searching the research literature. But very little solid information was available. The studies that existed were often based on a single event or on descriptions from doctors and nurses, not from the patients themselves.

In many of the surveys, it also seemed that the researchers were most interested in interpreting the phenomenon according to their own convictions.

For parapsychologists, the dreams served as evidence of ghosts or an afterlife. Freudians saw them as an expression of repressed longings. For theologians, the dreams hinted at the existence of God.

But Kerr was not that interested in evidence for either Our Lord or Freud's theories. He wanted to know: How is the phenomenon experienced by patients? And what meaning do the dreams have for them and for preparing to meet death?

There was only one thing to do: Study the topic himself.

- RELATED: Normal to feel presence of the dead

Documented experiences

Now, 20 years later, Kerr and his colleagues have published a series of studies on end-of-life dreams and visions. The surveys are based on interviews with patients that the researchers followed through their last months, weeks and days.

Their findings show that the phenomenon is very common.

A study from 2014 concludes that most patients had at least one episode where they experienced special dreams or visions that felt very vivid. Half of them had the experiences while sleeping, and the rest saw the visions while awake.

Many of the dreams included encounters with dead or living friends or family members, and sometimes pets.

The closer to death the patient was, the more often the dead appeared in their dreams. These meetings also seemed to provide more comfort than dreams about living people or other events.

In many cases, patients experienced that the dreams provided comfort and peace, or reconciliation with difficult events in life – and even reconciliation and peace in the face of death itself.

Kerr emphasizes, however, that death did not necessarily come as a mild embrace or that dreams and visions always bring relief and comfort.

«Up to 18 per cent of end-of-life dreams among our study patients were distressing in nature», Kerr writes.

Helped with grieving

Despite the upsetting nature of some of the dreams, a study from 2020 showed that patients who had the special dreams more often experienced post-traumatic growth, and felt strengthened and mentally stronger after their dreams.

Studies have also shown that the dreams of the dying affect the relatives. Family and friends of patients with good dreams and visions found that they helped in the grieving process.

But the attitudes that loved ones hold towards these strange dreams seem to make a difference. Many patients are reluctant to talk about their visions.

They are afraid of being considered crazy and may not dare to share their experiences, even with their loved ones – often with good reason. Very few people realize that this phenomenon is common, and telling people that you see things that don’t exist is rarely helpful.

That could be a problem, according to Kerr and colleagues.

A study published in 2021 showed that positive attitudes towards dreams and visions were strongly linked to a better grieving process for both the patient and the family.

And here we arrive at what Kerr perceives as the heart of the issue:

We have to stop keeping silent about this phenomenon!

Kerr believes that whatever these dreams are, they appear to be part of a basic human ability to help ourselves in the last hours.

When we conceal and ignore this phenomenon, we are wasting a powerful tool to cope with and tolerate the most difficult things in life.

Just delirium?

Reading about the research and stories of the American hospice doctors, it’s hard to believe that it's possible to overlook these characteristic events at the end of life.

But what is the status of this phenomenon among researchers in Norway? Do they have any awareness of the strange dreams of the dying?

At first, it appears not. ScienceNorway.no did not find any researchers who were studying this topic.

Lovisenberg Lindring og Livshjelp in Oslo – a centre for the treatment of patients who are dying or seriously chronically ill – had no one we could ask about the topic. They suggested contacting someone who works with delirium.

Perhaps here is where a bit of the problem lies.

Delirium is very common in serious illness and the last phase of life, where the brain's functions are failing and result in a state of confusion.

- RELATED: When is a visit by your deceased uncle a spiritual experience, and when it is a mental illness? It’s not always obvious, one psychiatrist says. More about this in the article Hallucinations or spiritual experiences?

Fear and horror

As in Kerr's dreams, delirious patients also experience seeing visions. Have doctors and nurses perhaps simply perceived patient tales of strange dreams as a form of confusion or delirium?

“I think that there has to be a large overlap here,” says Leiv Otto Watne in the Department of Geriatric Medicine at Oslo University Hospital. He is one of the few researchers, both in Norway and in the world, who does research on delirium – another very common but seldom explored phenomenon.

Watne questions how one can distinguish between the two. But Kerr, who has researched both phenomena, believes the differences are significant. Unlike delirium, dreams and visions are structured, meaningful and often positive.

Watne confirms that there is a big difference.

“Delirium is rarely perceived as positive. On the contrary, it’s often unsettling and frightening,” he says.

Patients might encounter ghosts and monsters, or they are convinced that they are being poisoned or attacked with swords. They don’t understand where they are and might fight for their lives against a doctor who wants to administer medicine.

Other patients might not act out as much and are thus not discovered. Afterwards, they might not dare tell either the doctor or the family about these experiences.

“It's a huge problem. Experiences like this can be traumatic enough to cause PTSD,” says Watne.

He believes we need to learn more about the phenomena and praises Kerr and his colleagues for studying it.

So does Øystein Buer, a hospital chaplain at Rikshospitalet in Oslo.

He himself is studying near-death experiences.

Near-death experiences

“Yes, I work with near-death experiences. We’re currently collecting data from patients,” says Buer.

Some patients who are revived after teetering on the brink of death – for example from cardiac arrest – tell about profound experiences from the time they were technically dead. These are called near-death experiences.

Buer emphasizes that this is not the same as Kerr's end-of-life dreams, and that his (Buer’s) comments should be seen in light of the fact that he has not researched dreams and visions. That being said, one cannot deny the fact that the two phenomena have numerous similarities.

Both near-death experiences and end-of-life dreams can occur in conscious and unconscious states. They are often about deceased acquaintances, and both frequently seem to have deep meaning for the patients.

Value underestimated

Buer actually also has some experience with stories about dreams and visions before death.

“I had a cancer patient who told me that he sat by his mother's sickbed when he was young. The mother had had experiences like this in those last days of her life, and they had made a deep impression on the son,” he said.

“They were so important that they came back to him when he himself was about to die.”

“I believe that health professionals who care for the dying have encountered patients who’ve had extraordinary experiences,” says Buer.

He has no doubt that we should talk more with dying patients about what they are experiencing – both the negative and the positive.

“The value of these experiences for patients and relatives is underestimated. It’s a bit taboo to talk about a topic that borders on the spiritual and the existential. But it’s important to note the experiences as resources,” Buer says.

- RELATED: How should nurses provide for patients’ spiritual needs, especially at the end of life? More in the article Bringing spirituality and religion to elder care

Existential challenges

Stein Kaasa, a professor at the University of Oslo and NTNU, is also aware that many dying patients can have extraordinary experiences. He works with people with incurable cancer and has met many patients in the last days of life.

“People will tell you a lot of different stories, if you’re open to them,” he says.

“I’ve found that talking about this creates a good atmosphere and a starting point for a good conversation with seriously ill people. But unfortunately, this dimension isn’t sufficiently present in our consultations with patients,” Kaasa says.

He believes a lot of patients have existential challenges that they need to talk about, regardless of whether they have religious beliefs or not.

“But there’s not enough focus on that,” he says.

Not so concerned with the patient

Kaasa believes there are several reasons why experiences like dreams and visions rarely come up in conversations between the doctor and seriously ill patients.

For one thing, many physicians are likely reluctant to address anything that borders on a patient’s soul life and spirituality.

Another more general issue is that the field of medicine is simply not adequately concerned with the patient. The focus of research and treatment is the cancerous tumour – not the patient that has the tumour.

“I think in principle that we should be doing more research on patient-centred phenomena. Medicine isn’t curious enough about the person behind the disease,” says Kaasa.

Could this be an explanation for the fact that hardly anyone nowadays knows that dying people have dreams and visions?

Kaasa believes there is little reason to doubt that a lot of people have these experiences.

“The phenomenon is well enough documented,” he says.

Now we should move on to the next big question: How do we relate to these experiences?

“We should design a study to test the effect of addressing this topic in patient conversations. This research is lacking,” says Kaasa.

At the boundaries of science

Hospital chaplain Buer wouldn’t mind if researchers investigated a possible connection between deathbed dreams and visions, and the near-death experiences that he himself is studying.

What actually lies at the bottom of all these experiences?

Are the dreams a kind of advance near-death experience, as part of more universal experiences of encountering death?

Comparing cultures would also be interesting.

Buer wonders if people have universal, fundamental human experiences that they interpret based on their own personality and culture.

But when it comes to the deepest questions about death, we are unlikely to find any answers.

“Science has its own rules and methods. At a certain point you reach the limit of what it can say about some things,” says Buer.

Won’t speculate

Kerr also stops at this juncture.

As a lecturer, he admits that he sometimes tries to escape from the podium before anyone in the audience has time to ask the question that always comes up: What do you think this really means?

He has no answer.

“I can’t begin to speculate on an afterlife or on God's larger plan, which is what many people really want me to talk about,” Kerr writes in his book.

He believes one point is precisely that the dying process is about more than what comes afterwards. The time before the end is interesting in itself, not just as a precursor to something else.

«Dying is more than the suffering we either observe or experience», Kerr writes.

In the midst of tragedy, processes also take place that are meaningful for patients. As bodily functions are failing, the spirit is sharpened.

“They experience a growing sense of connectedness and belonging. For me, what it all means is that the best parts of living are never truly lost,” says Kerr.

References:

Tatsuya Morita et.al.: Nationwide Japanese Survey About Deathbed Visions: "My Deceased Mother Took Me to Heaven", Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 2016.

Sandhya P Muthumana et.al.: Deathbed visions from India: a study of family observations in northern Kerala. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 2010. Summary.

Allan Kellehear et.al.: Deathbed visions from the Republic of Moldova: a content analysis of family observations. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 2012. Summary.

Christopher W Kerr et.al.: End-of-life dreams and visions: a longitudinal study of hospice patients' experiences. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 2014. Summary.

Kathryn Levy et.al.: End-of-Life Dreams and Visions and Posttraumatic Growth: A Comparison Study. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 2020. Summary.

Pei C Grant et.al.: Family Caregiver Perspectives on End-of-Life Dreams and Visions During Bereavement: A Mixed Methods Approach. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 2020.

Pei C Grant et.al.: Attitudes and Perceptions of End-of-Life Dreams and Visions and Their Implication to the Bereaved Family Caregiver Experience. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care, 2021. Summary.

C. W. Kerr & C. Mardorossioan: Death Is But a Dream: Finding Hope and Meaning at Life’s End. Penguin Random House, 2020. Summary.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no