UN Lebanon-mission in 1978:

Norway wanted to support the UN and the US – sent troops off in a hurry without really understanding the consequences

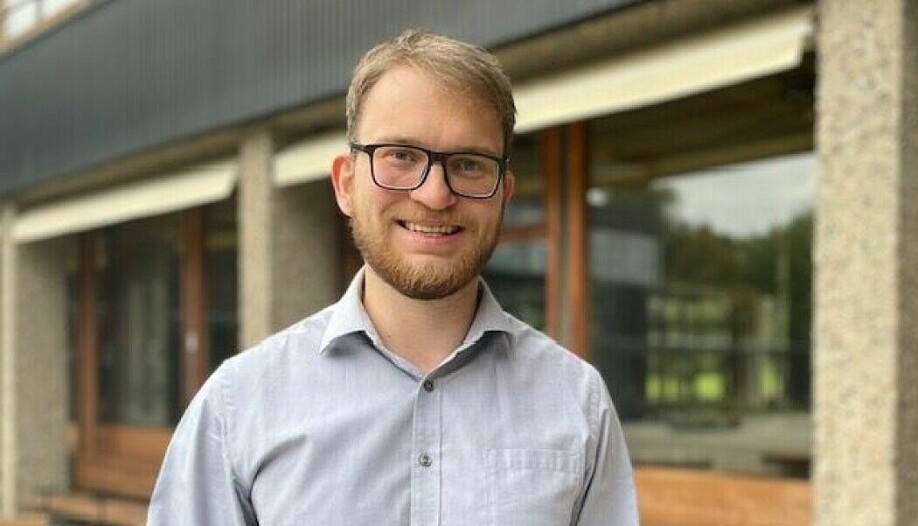

Historians have now gone through classified documents to understand what really happened behind the scenes when Norway almost immediately agreed to participate in the UN force. Former UNIFIL soldier Harald Stanghelle is sceptical of some of the researchers' analyses.

More than 21 000 Norwegian troops served in the Norwegian UNIFIL force in Lebanon between 1978 and 1998.

Twenty-one of them never came home again.

The researchers posed the question:

Why did the forces in Lebanon stay until 1998 – even though they realized that they would not be able to fulfil the UN mandate and the situation was going from bad to worse?

The study is discussed in an article in Historisk Tidsskrift , the Norwegian history journal, written by historians Robin Sitter and Hilde Henriksen Waage.

Waage is a professor of history at the University of Oslo, where Sitter is a research assistant.

Sent to maintain peace

In April 1975, civil war broke out in Lebanon.

The war contributed to the country falling apart. The Lebanese authorities no longer had control over their territory.

In southern Lebanon, Palestinian groups attacked Israel from Lebanese soil. Israel responded by occupying parts of Lebanon in March 1978.

UNIFIL was set up to oversee the Israeli withdrawal from southern Lebanon.

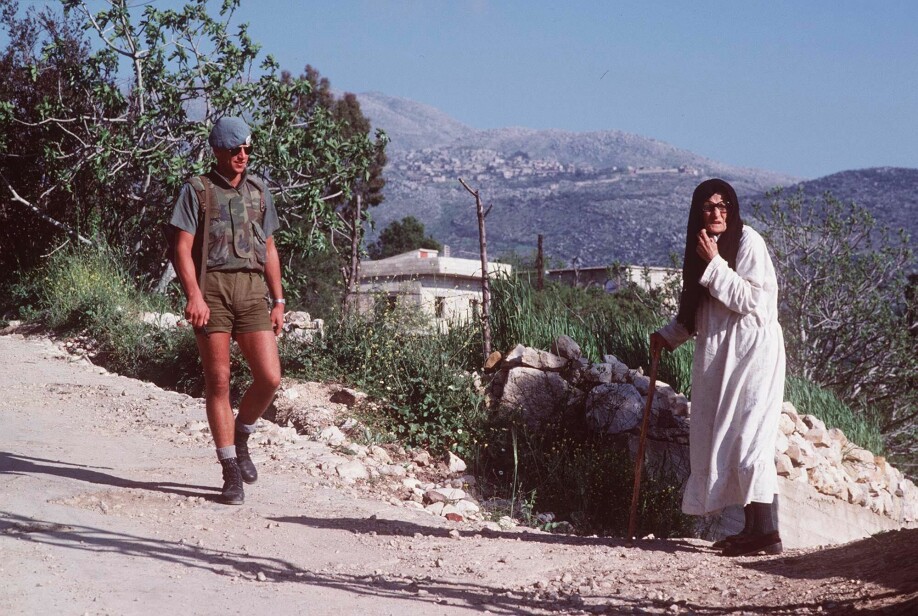

The UN force was sent to maintain peace and security in the area and to assist the Lebanese authorities in regaining control.

No peace awaited in Lebanon

The Norwegian soldiers were sent off in a hurry, several of them with equipment that didn’t fit. The soldiers met anything but peace and stability in Lebanon.

“A lot of the equipment the soldiers brought with them was still wet from the previous winter’s exercises,” says Sitter.

He was given access to restricted government notes on UNIFIL and Norway's role in Lebanon, which researchers had never looked at before. This became his master's degree. Now Historisk Tidsskrift has published an article based on the study, which he wrote with Waage.

King flown in from Easter holiday

In studying the notes, Sitter discovered that the decision to send Norwegian soldiers to Lebanon was made in a hurry.

This happened in the middle of the Easter holidays in 1978.

“The government had to convene the Council of State. But both the King and the Prime Minister were on Easter holiday. Eventually they were reached, and the King was then flown in from the mountains by helicopter,” Sitter says.

Norwegian politicians and the civil service received a request from the UN on 20 March to contribute forces.

They answered yes on the same day.

The mobilization order was sent to the Armed Forces, which quickly provided troops.

Within the space of a few days in March and April 1978, approximately 700 Norwegian soldiers were stationed in Lebanon.

Happened on autopilot

“Our conclusion is that at this speed, things happened on autopilot without the Norwegian authorities having carried out any assessments of their own,” Sitter says.

Previous research, such as that of historian Olav Riste, has justified Norway's presence in Lebanon on the grounds that Norway wanted foreign policy to serve Norwegian interests and ideals. What was good for Norway was also good for the world.

But Sitter's study shows there was no fundamental discussion behind this decision.

“Consideration for the UN and the USA was what mattered. No independent assessment of the situation on the ground in Lebanon was made. As long as emergency preparedness here at home wasn’t compromised, we joined in.”

- RELATED: Did you know that Norway dropped nearly 600 bombs on Libya in 2011, but had little to do with deciding where those bombs should fall.

No ceasefire desired

US President Jimmy Carter reacted strongly to Israel's invasion of southern Lebanon. He was concerned about the consequences it might have for the ongoing peace talks between Egypt and Israel.

Carter feared that this window to peace would now be closed.

That is why the Americans pressured the Security Council to establish a peacekeeping force in Lebanon. The mandate was to monitor the Israeli withdrawal, create peace and security and help the Lebanese gain control of their own territory.

But Israel, the PLO and Syria didn’t want any UN forces there. Nor was there any ceasefire between the parties.

Other UN operations similar

Most UN operations during the Cold War used exactly the same pattern of action, Sitter found. He has also reviewed several of the other UN missions in which Norway has participated.

“It’s pretty interesting that things happen so quickly. The military we had at the time was a massive mobilization defence that is actually supposed to take some time to become battle-ready.

“But with the UN missions, this all happens within a few days,” Sitter says.

Came to a war zone

The Norwegian Minister of Defence Rolf Hansen wanted assurances that the force would not be deployed in areas with combat operations, and that there would be a ceasefire. Israel and Lebanon should also agree that UN forces were desirable.

But it was far from peaceful in Lebanon when the first troops arrived in the country.

The area the UN force was to enter was a war zone. The soldiers encountered life-threatening situations and quickly ended up in the crossfire between different groups fighting each other on the ground in Lebanon.

As early as 6 April, Norwegian forces were shelled.

Chief of Defence Sverre Hamre had warned about this. He believed that Norwegian soldiers were not mentally prepared for what they would encounter in Lebanon.

A lot of these soldiers still struggle with post-traumatic stress symptoms today. It’s clear that the Armed Forces bears great responsibility for the fact that many of them haven’t coped well.

"The government was so eager to support the UN and the United States that it made decisions without fully understanding the consequences," the researchers write in Historisk Tidsskrift.

Armed Forces bear great responsibility

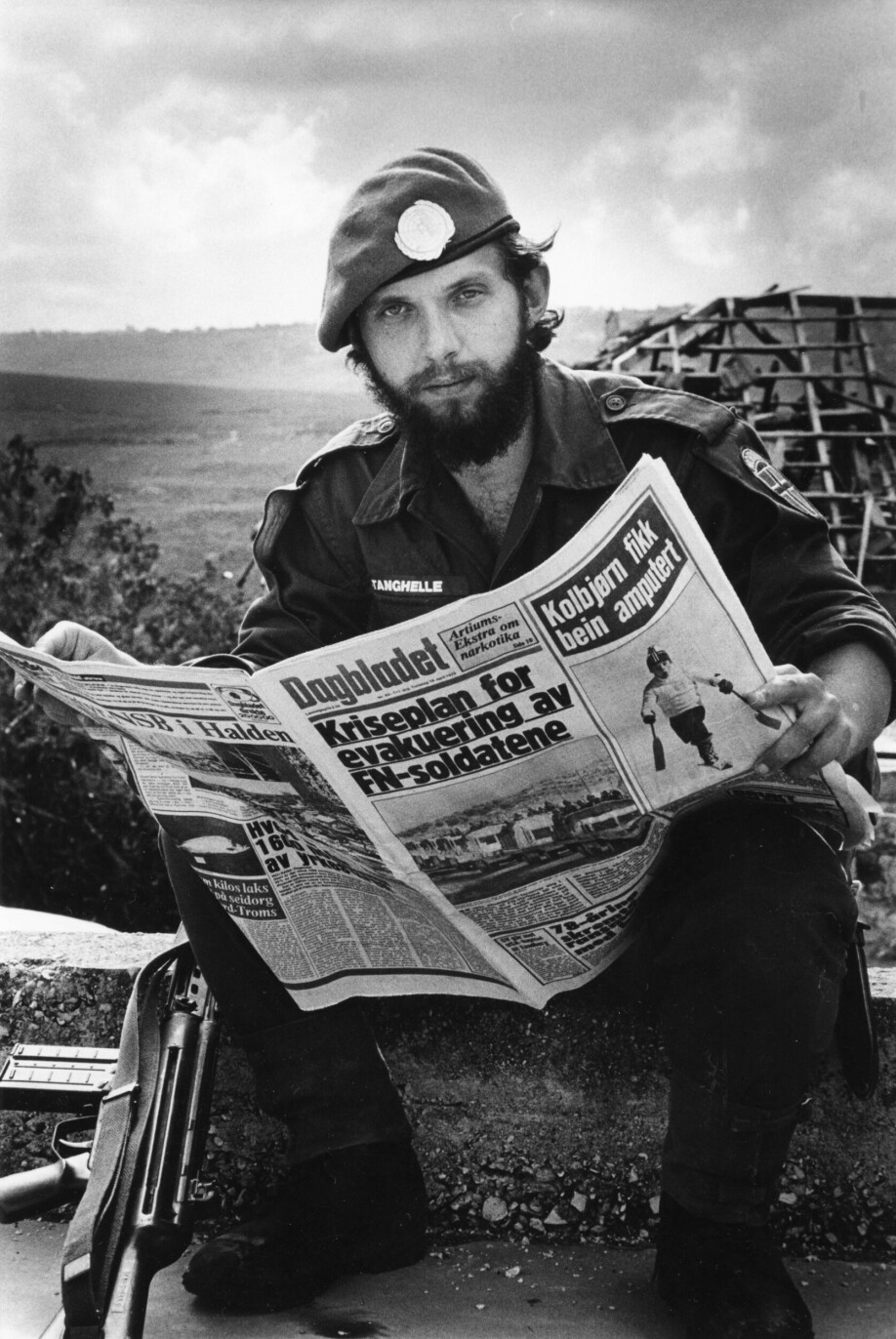

Harald Stanghelle, who covered the Middle East for the Norwegian newspaper Arbeiderbladet throughout the 1980s and later became editor of the Dagbladet and Aftenposten papers, was one of the Norwegian soldiers who came to Lebanon early.

He remembers the day very well.

Stanghelle arrives in Beirut on 26 March 1979. There is a lot of shooting in the city. Both the Palestinians and the Lebanese were furious and protesting against the new peace agreement between Israel and Egypt.

In terms of whether the Norwegian forces were mentally prepared for so much conflict in the area, Stanghelle says they were not.

“Three weeks after my battalion came down, there was an Israeli attack on the city where we were stationed. One Norwegian UN soldier was killed and another was seriously wounded. Clearly this was a situation that we were neither mentally nor in any other way prepared for.”

At the same time, Stanghelle believes the Norwegian soldiers handled the situation very well.

“However, there was no debriefing after the incident. The Armed Forces hadn’t established any such schemes. A lot of these soldiers still struggle with post-traumatic stress symptoms today.”

“It’s clear that the Armed Forces bears great responsibility for the fact that many of them haven’t coped well,” says Stanghelle.

Analysis has some shortcomings

Stanghelle thinks that what the researchers have found is interesting. But he also believes that Sitter’s and Waage's analysis has a number of shortcomings.

Stanghelle is surprised that the researchers make only brief mention of something he believes is an important reason why UNIFIL could not succeed.

“The precondition for UNIFIL was that Israel would withdraw from Lebanon and hand the area in southern Lebanon over to the international forces. That didn’t happen. Israel refused to hand over the area to the UN force. Instead, they established an enclave in southern Lebanon where an Israeli-backed Lebanese militia was allowed to take control.”

This enclave was not recognized by any other country. It became the starting point for a great deal of unrest in the years that followed. The Norwegian UN force had the enclave as its closest neighbour and its biggest problem. Stanghelle believes the researchers did not problematize this point.

Sitter thinks Stanghelle’s criticism is misplaced and obscures their findings.

“Our focus in the article is the Norwegian politicians' decision to send and maintain the Norwegian mission, not why UNIFIL in general wasn’t able to fulfill the mandate of the UN Security Council,” says Sitter.

1982 – a dramatic year

The situation in Lebanon changed dramatically in 1982, when Israel invaded Lebanon again. The goal was to remove the PLO from the country.

The researchers wonder why this has not created unrest in Norwegian politics.

The political documents that the researchers reviewed show a completely different picture. While the Norwegian military expresses that they do not see the benefit of this Norwegian UN mission and want to withdraw from Lebanon, no new assessments are forthcoming from the politicians.

They take a wait-and-see attitude. But now the soldiers are given the additional assignment to protect the civilian population.

“Norwegian politicians say they are happy with this. And the mission also motivated the soldiers, who had built a very close relationship with the local population,” Sitter says.

The die was cast

The mission in Lebanon was supposed to be temporary.

But not until 1998 – after 20 years – did the Norwegian UNIFIL force withdraw from Lebanon.

There were three reasons why it took so long, according to the researchers.

First, a withdrawal would threaten stability in the Middle East. Secondly, the Norwegian authorities did not want to put the UN in a difficult situation.

And finally, Norway's support for the UN also supported the United States.

“The Norwegian authorities worried that a withdrawal would provoke strong international reactions. The fact that Norwegian soldiers were sent to UNIFIL on autopilot meant that they had no exit strategy,” says Sitter.

Not entirely fair

Stanghelle isn’t sure it’s a fair description to say that the decision to participate in UNIFIL happened on autopilot.

“Norway had a fundamental interest in staying on the right side of the United States, which the researchers mention as well. That becomes part of the rationale in deciding to send the troops,” he says.

“Sitter and Waage also emphasize in their article that our view of the UN is a mainstay in Norwegian foreign policy. So I’m a little surprised when they go on about Norway not independently assessing its participation in UNIFIL. When two of the pillars of Norwegian national security – relations with the United States and relations with the UN – pull in the same direction, that would naturally heavily influence politicians to say yes."

Plenty of hindsight

Stanghelle stresses that this research is useful. But he believes it is also based on a lot of hindsight.

“When you’re in the middle of a situation, you see some things that are important for the decision, but you don’t see other elements. I think that the researchers' wording is a bit cocky. The Norwegian authorities didn’t have a lot of room to manoeuvre at the time,” he says.

In response, Sitter notes that the researchers present the situation based on how the Norwegian authorities assessed it at the time. How they weighed the pros and cons is reflected in the government notes reviewed by the researchers.

“Contemporary knowledge is not the same as hindsight,” says Sitter.

He also disagrees with Stanghelle that Norway did not have room to manoeuvre.

“You have as much room to manoeuvre as you give yourself. Norwegian authorities assessed withdrawing from Lebanon, but concluded that the arguments against doing that weighed more heavily. The Netherlands, a comparable country, chose to withdraw its forces in 1995,” Sitter says.

A piece in the game

Stanghelle thinks the most accurate part of the researchers’ article is its title: 'The immovable pawn.'

He says, “UNIFIL became a piece in a game that everyone hoped would have a stabilizing effect. In some phases, it probably also worked that way, especially in the period from 1979 to 1982 and perhaps also after the Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon in 1985.”

Took too many resources

The operation in Lebanon eventually gobbled up too many resources from the Norwegian Armed Forces, particularly when the Balkan conflict began to heat up in the 1990s.

The mission in Lebanon ended in 1998 and the UNIFIL soldiers withdrew. The dissolution of Yugoslavia and the wars in the Balkans became the next hotspot that required Norwegian efforts.

Reference:

Robin Sitter and Hilde Henriksen Waage: En brikke ingen turte røre: Norges fredsbevarende bidrag i Libanon 1978–1982. (The immovable pawn: The Norwegian contribution to the peacekeeping operation in Lebanon 1978–1982), Historisk tidsskrift, 2021.

———