Norwegian Air Force left decisions to others in Libya

Norway dropped nearly 600 bombs on Libya in 2011, but had little to do with deciding where those bombs should fall.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

If Norway drops the bombs, should its decision makers demand a say in the strategic command of operations?

Researcher and Lieutenant Colonel Dag Henriksen at the Norwegian Defence University College pondered exactly this question in a Norwegian journal on international politics.

When Norwegian fighter jets joined the military operations in Libya in 2011, the Norwegian Armed Forces surprised itself and others by being rather gung ho, according to Henriksen.

Norway carried out around 15 percent of all the airstrikes in the beginning of the operation and took on missions that other countries declined.

But Norwegians were not involved in deciding which targets the international forces should concentrate on.

“There’s a myriad of things you can do under the kind of mandate we had in Libya. You can take out targets in big cities, you can direct attacks at individuals or vehicles, and so on,” says Henriksen.

“These issues were primarily discussed at a military operations level, but Norway didn’t participate at that level. You can question whether this was advisable, considering the scope of Norway’s contribution.”

Getting used to exercising force

No Norwegian bombs fell on Kosovo when Norway joined the international forces there in 1999. In Norway’s two periods of operations in Afghanistan [Operation Enduring Freedom and ISAF], it only dropped seven bombs.

But in Libya that number jumped to 588.

“We were willing to carry out politically sensitive missions in the beginning, missions that many other countries wouldn’t or couldn’t carry out,” says Henriksen.

The targets Norway bombed are classified information. But in general they often involved missions that could be hard to sell to politicians or the press – for instance bomb runs in cities where the distance from the target to civilians is short.

“Other NATO countries, and I think those of us in Norway’s armed forces and political leadership, were surprised about how heavily involved we got in Libya. I don’t think anyone anticipated this when the decision to go in was made,” says Henriksen.

“From being very uncomfortable about getting involved in Kosovo 12 years ago, it now seems we’ve become accustomed to using force.”

When one country is behind nearly a sixth of the combined air strikes in an operation, it also has an impact on the development and outcome of that operation.

“We were involved in the framework of the war. We took out targets that others didn’t want to get involved with. After things went well in terms of politics and the media, others changed the way in which they participated,” says Henriksen.

Could have influenced operations

What impact did the Norwegian use of air power have? Was it the effect that Norwegian pilots had flown down to an airbase in Crete to achieve?

The military operations in Libya were aimed at protecting civilians in the East of the country. The justification was that international society can intervene in a country if the civilian population is in danger.

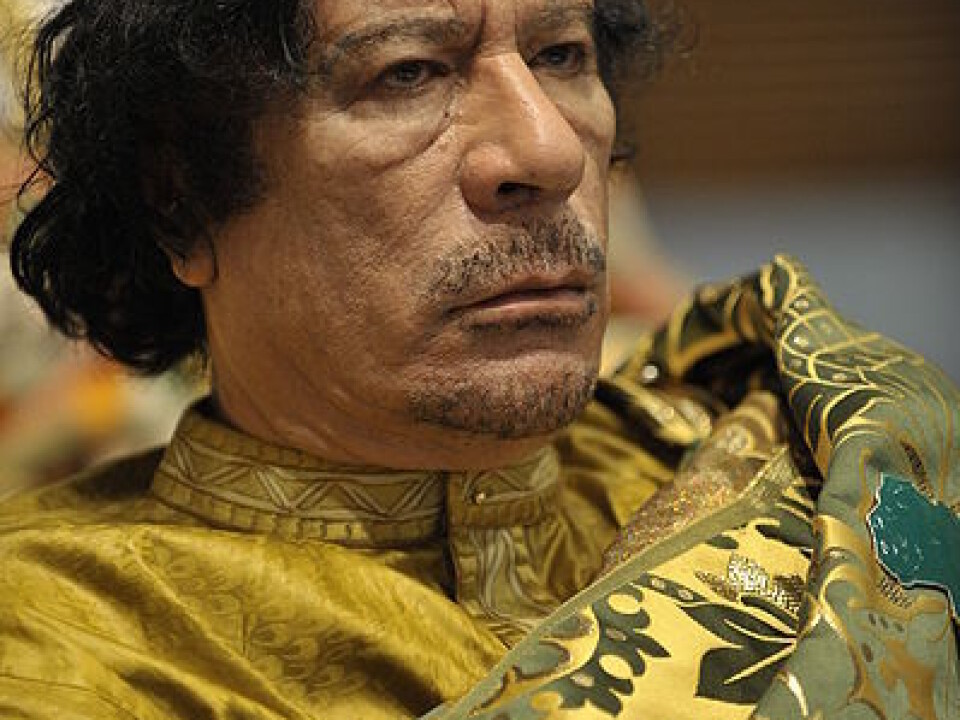

According to the UN mandate, NATO wasn’t supposed to remove Libya’s President Muammar Gaddafi from power.

“But the result was a regime change, we know that now,” says Henriksen.

“It’s debatable now whether this type of mission, called ‘the responsibility to protect’, has been undermined after Libya. The fear is that it’s more likely that such initiatives will be seen as false pretences.”

The protection of the public requires a different approach than expelling a regime. Did the participants in the Libya operation make the right choices? Were the selected targets the most pertinent with regard to the UN mandate, which focused on providing protection to the local population?

“If Norway had been involved in Libya on the operational level, in selecting targets, we could have aired Norwegian perspectives in these discussions,” says Henriksen.

Real influence on the outcome

A special kind of expertise is needed to decide which bomb targets have the best potential for achieving specific political and military goals. Norway hasn’t given priority to building this kind of expertise, and the Armed Forces Operational Headquarters says that only four or five people are currently assigned to this kind of work.

The lieutenant colonel stresses that Norwegians shouldn’t be naive. Their country is small and others were more heavily involved and had more of a say.

Usually Norway has been satisfied by contributing with tactical capacity – for instance with aircraft, ships and a few soldiers – and with letting NATO decide how to use them.

“At the root of this was the assumption that Norway was too little in any case to take responsibility for the outcome of an operation. But now we’ve seen that Norway can have a real impact,” says Henriksen.

New demands with new fighter jets?

Henriksen stresses that Libya might be the proverbial exception confirming the rule. Norway could play a much smaller role in the next operation of this sort.

But we don’t know that yet, so politicians and the Norwegian Armed Forces need to embrace this new reality.

“Norway is now buying one of the world’s most advanced fighter jets. Other countries are bound to request its use in future operations,” says Henriksen.

“If we want to have any influence on decisions about its use, we’ll have to bolster our competence and also participate in decisions made at the operational level.”

Translated by: Glenn Ostling