Can Covid-19 lead to poorer memory? A study of over 100,000 individuals faces criticism

When participants assess their own memory, they may think it is worse than it is.

Last week,

researchers from Oslo University Hospital published a study on memory problems and Covid-19.

Sciencenorway.no and several other media outlets wrote that the study showed that people who have had Covid-19 have a poorer memory than people who have not had it.

But is this correct?

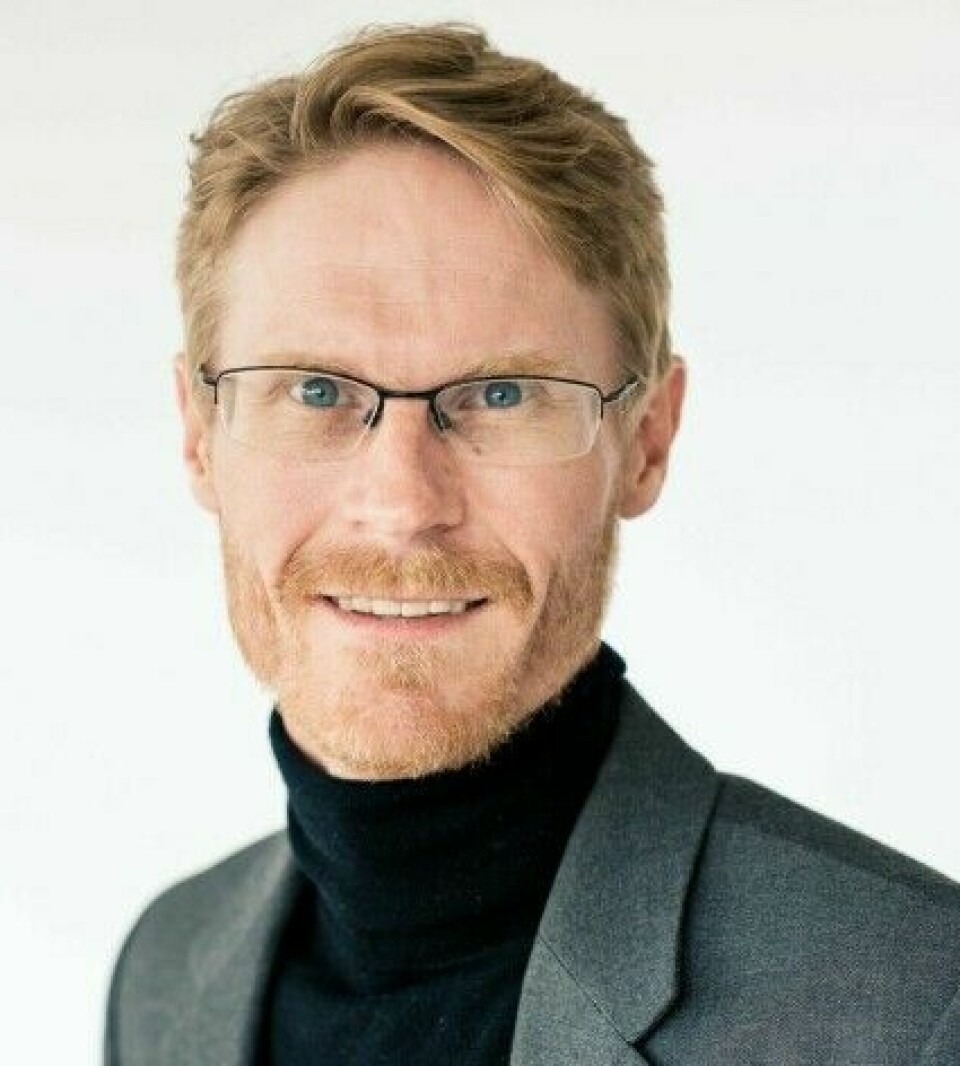

Sciencenorway.no consulted with statistician Inge Christoffer Olsen, who points out several issues with how these findings have been portrayed.

Critical of the interpretation in the media

Olsen thinks the study is well conducted. What he is critical of is the portrayal in the media.

“The way newspapers, including both journalists and the research team, have interpreted the study does not hold up,” says Olsen, who researches medical statistics at Oslo University Hospital (OUS).

The findings of the study could be attributed to factors other than the infection itself.

Limitations of self-reported data

The conclusion in the scientific article actually differs from how it is portrayed in the media. In the study, the researchers conclude that those who tested positive for Covid-19 reported worse memory than those who tested negative.

This does not necessarily mean that there is a causal relationship between the virus and the memory.

Participants filled out a questionnaire about how they experienced their own memory. For example, how often they forget when events occurred or where they have put things.

May answer differently

Although this is a common and recognised questionnaire for measuring memory, it is not an objective measure.

Those who have tested positive for Covid-19 may simply perceive their own memory to be worse than it actually is.

“When you know you've had Covid-19 and have heard all the talk about brain fog, you might respond a bit differently than if you haven't had it, but have had the exact same symptoms,” Olsen explains.

Not random who responds

Moreover, who chooses to respond to the survey can create an artificial difference between the groups.

“If it had been completely random who did or did not respond, then it would have been a representative sample. But if it’s the case that those who have had Covid-19 and are experiencing brain fog respond more often, then there will be a bias,” Olsen says.

The researchers behind the study have mentioned these two weaknesses in the original study, but the caveat has disappeared in the media’s reporting of the findings, the statistician points out.

The researchers agree with the criticism

“We agree that we cannot definitively say that memory problems are caused by Covid-19 based on this publication alone,” says Arne Søraas, one of the three researchers behind the OUS study.

He mentions there are several reasons for this, including that this is not a randomised study.

“We also agree with Olsen that the weaknesses of the study may not always have been adequately highlighted in the media,” says Merete Ellingjord-Dale.

She is also one of the researchers behind the study, alongside Søraas and Sonja Brunvoll.

“Self-reporting is always a limitation in research, including in the questionnaire we used about memory problems. Self-reporting can lead to information bias, which might mean certain groups, like those who have had Covid-19, perceive their memory as worse than others,” Brunvoll explains.

Not sensational

“However, it’s not very sensational to point out that memory is part of Covid-19,” says Søraas.

Previous studies, including those from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, have shown the same correlation.

“Our summaries of knowledge from international research and our own research have also identified memory problems as part of the long-term effects of Covid-19,” Jan Himmels writes in an email to sciencenorway.no.

He is a senior adviser at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

“We have long known that memory problems are among the commonly reported symptoms of the long-term effects after Covid-19,” he writes.

Arne Søraas states that their article should be viewed in the context of other research.

“It's essential to always consider this context. This includes everything from earlier observational studies to studies showing changes in MRI images of the brain. We must also pay close attention to the experiences patients are sharing with us at this moment,” Søraas advises.

Small difference between the groups

Inge Christoffer Olsen also points out another weakness.

The difference in self-perceived memory is relatively small between those who tested positive and those who tested negative for Covid-19.

So, if some of this difference is actually due to the method used in the study, then the real impact of the virus is even smaller.

“When Olsen looks at the average and says the difference is small, I would say that behind this average, there might be subgroups that are more distinctly separated from each other in scores on the memory questionnaire,” says Søraas.

‘Although the average difference between individuals who tested positive and those who tested negative for Covid-19 is relatively small, significant differences persist across various points, up to three years following their test,’ Ellingjord-Dale notes.

Subjective experiences of memory

Roald Omdal is professor emeritus and senior researcher at Stavanger University Hospital.

He believes the OUS study is important and confirms that long Covid ‘is not to be taken lightly’.

‘The study underlines the presence of enduring issues in some individuals post-infection, with no apparent improvement even after three years of monitoring,’ Omdal writes in an email to sciencenorway.no.

Regarding the issues related to self-reporting, Omdal agrees that it is the participants’ subjective experiences of memory problems that are reported.

For instance, no neuropsychological tests were conducted by professionals to map out each individual’s function.

“On the other hand, there is a very large dataset where the same questions are asked and which provides consistent responses over time,” according to Omdal.

Persistent functional impairment

Even though the difference in memory problems between the groups was relatively small, Omdal considers it an important finding.

Especially because there are so many participants in the study.

“This means that for some, there will be greater memory problems, and for others, this will be of less significance. Overall, the study is important because it indicates that there is a subjective experience of functional impairment that persists,” writes Omdal.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no