A spool of cotton thread ushered Norway into a new age.

It became an industrial country. And women got paid work.

But cotton has a bloody history.

This cotton spool changed Norway

Hundreds of young women have the same goal at 6 o’clock one early morning in 1846.

The women are on their way to the factory. They work at the Vøien cotton spinning factory at Sagene, in Oslo.

They are Norway’s first industrial workers. They are at the centre of what historians will later call an epochal divide.

It has been 80 years since the first spinning machine was invented in England. Before, each skein of yarn had to be spun from wool to thread on a spinning wheel. Now the machine, which was called the Spinning Jenny, could spin many spools of thread at the same time.

And the raw material was no longer wool, but cotton.

The spies were after Jenny

The British textile industry had a big head start. This was the starting point for a completely new period in world history — the industrial revolution. But at first it was restricted — by design — to the UK.

Founders with capital from all over Europe watched with interest. They sent spies to check out Spinning Jenny and the factories in Manchester. The British guarded this new technology closely. It was strictly forbidden to sell drawings, machines or expertise.

After nearly 80 years had passed, England opened up.

It became too difficult to keep the spies away. There was also money to be made from the sale of both machines and know-how.

“Two Norwegian men then hurried to Manchester,” says Gro Røde, a historian and information officer for worker culture and industrial history at the Oslo Museum.

24-year-old entrepreneur

These two men are Knud Graah and Adam Hiorth. They meet each other in a pub and quickly realize that they are on the same errand. They want the first contracts for the new technology.

While Hiorth settles in Nydalen in Oslo, Knud Graah starts a spinnery at Sagene in a different part of the city.

“I’m impressed by Knud Graah — that he dared to do this! He was a brave entrepreneur who saw the opportunity to harness the power of the Akerselva River in new ways, for a new industry,” Røde said.

Graah is 16 when he moves to Norway from Denmark. He works his way up the ladder of his trade and is only 24 years old when he gets the contract in Manchester.

He gets capital from his sister Charlotte and brother-in-law Nils Young. Together they buy the rights to the waterfall at Sagene and build the country's first factory, Vøien bomuldsspinderi (Vøien cotton spinning) — later AS Knud Graah & Co.

Young women get jobs

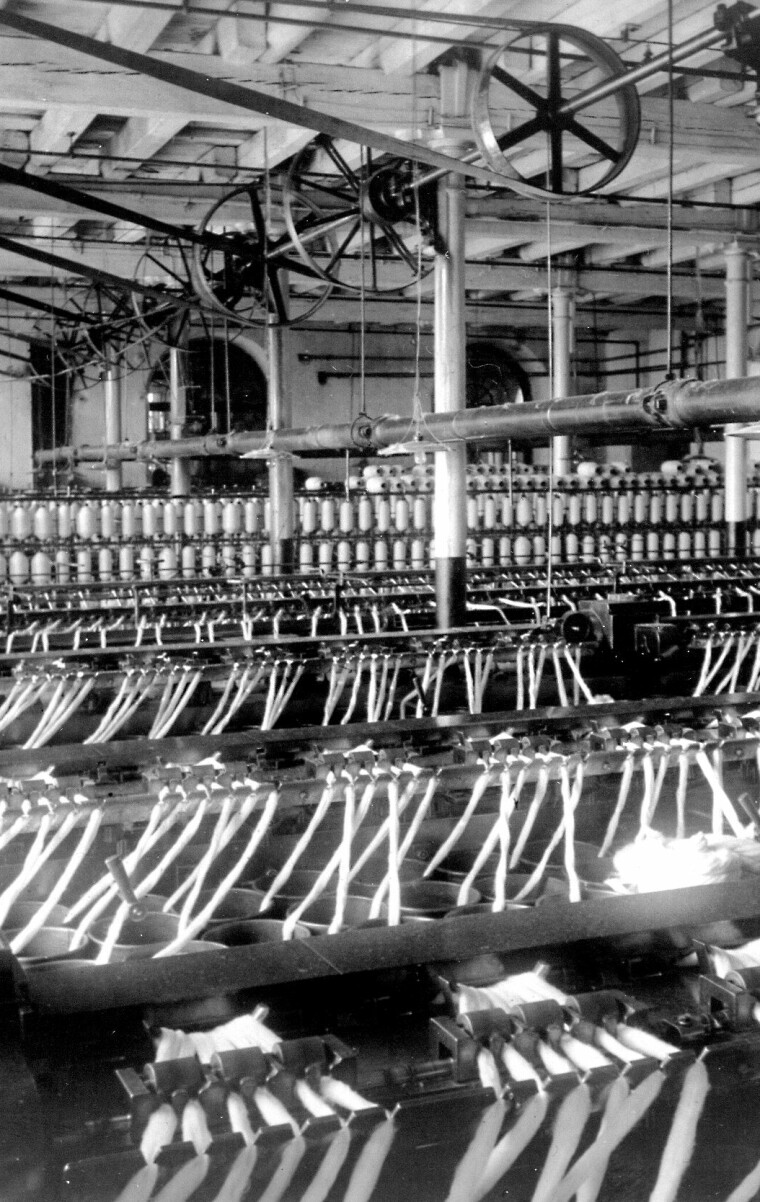

The machines come from England.

“The spool is placed into a shuttle and then shot into the warp. The technology makes it possible to produce large quantities of fabrics without manual labour, but with machines,” says Røde.

Graah makes agreements with workers and foremen, who move to Norway to train the factory's employees — who are young women.

“Women getting paid work is a social revolution. The majority of women who get a job in the factory are young, unmarried women aged 18 to 23,” Røde said.

Cheap, smart and easy to manage

There were many of them. Graah's spinning mill had more than 400 workers. A neighbouring company, Hjula weaveri, had close to 900 workers.

“We have theories as to why they employed women and not men. The factory needs the best workforce. They need workers who are handy, smart and who learn quickly. They also need to be easy to manage and not create problems. It was brilliant to employ young girls,” says Røde.

Female labour was cheaper. And there was a tradition in farming culture for women to spin and weave.

Knud Graah and other factory owners did as was done in England, they bet on the women.

Thirty per cent of the workforce was still men. They repaired, lubricated and adjusted the machines — and did maintenance work on the premises and buildings.

Stressful childcare

Many women left the factory when they got married, others continued until they became pregnant.

The Norwegian author Oskar Braaten has written several books where he describes female factory workers who have children but no childcare.

He writes about a mother who has to leave her children every morning before six o'clock. They are still sleeping. She cuts bread and puts it in the oven. Then she goes to work. When she stands by her spinning stool, her thoughts go to her children. Did they wake up in time for school? Did they get something to eat? Did they wash up? Did they take care of the wood stove and watch out for traffic? In the middle of the day, she has a break and can run home. Then she has to return for even more hours of work.

“There were private childminders, such as Hønse-Lovisa. The Salvation Army also offered childcare, where single mothers could drop off their youngest children. And children over the age of three went to the children's asylum. But this was the exception, most of the workers were unmarried, without children,” Røde said.

Hønse-Lovisa was a fictional older woman in one of Braaten’s books who offered care for single mothers and their children so that the women could work and not have to give up their children for adoption.

The first to offer free time

It was not easy to combine work with family. The women worked up to 12 hours a day.

Yet they had something that was completely new— free time. After their 12-hour work day, their evening was free. They also had half of Saturday and all of Sunday off.

“They were the first workers whose working hours were regulated. Maids and other house help hardly ever had time off. They had to adapt to the family they worked for. Nor could carpenters and other craftsmen go home until the work was done and their master gave them permission,” Røde said.

But conditions in these factories were bad.

Factory worker Anne Pleym described dark, gloomy factories in the 1880s. The machines were placed so close together that it was difficult to walk between them.

The cotton was not fully cleaned when it arrived at the factory. The cleaning and the machines produced a lot of lint and dust — which people inhaled. It made workers sick.

Then there was the noise.

Getting accustomed to the noise

The racket inside the factories was described in a book commemorating Knud Graah & Co.’s 50th anniversary, but the book claims that workers were able to tolerate the noise:

"For people who are not used to moving around in a textile factory, the noise in the weaving hall will be deafening, and it seems impossible to carry on a coherent conversation in such noisy surroundings. The workers, on the other hand, who are in the room every day, soon get used to the noise and can easily communicate with each other...”

These young factory workers were part of the Norwegian industrial revolution from day one, Røde said.

Many historians believe it was less of a revolution in Norway and more of a slow evolution involving many factors. Starting in the 1830s, the Norwegian economy was expanding. Exports of fish and timber were on the rise. Shipping had its glory days. New technology had arrived, with steam turbines and more efficient use of hydropower.

“I would still call it a revolution. Three textile factories quickly scaled up to major production, which was technically and mechanically demanding. This led to many new industrial jobs. Norway was quickly becoming an industrial country,” Røde said.

The spool of cotton thread led to big changes. Many earned money, both large and small sums, from the new industry. But there was a downside.

Slavery made it possible

Where did the cotton come from? Who picked the cotton?

Slaves in the American South provided the raw material for Norway’s industrial adventure.

“In the first years of Norway’s textile factories, the cotton is picked by slaves, who are exposed to the worst human condition possible. They are a commodity. Their labour makes textile production in Norway possible,” Røde said.

The human cost of cotton is not detailed in Knud Graah's 50th anniversary book:

"It is no coincidence that America systemised cotton cultivation. The favourable climate in the Gulf states, the exceptionally fertile soil, and not least the easy access to labour, naturally made for a strong development."

The American Civil War from 1861 to 1865 ended slavery. But Graah’s book says that freed African-Americans continued to thrive in the cotton fields with “pleasant work and a carefree life". According to the company, the former slaves’ enjoyment of their work comes from "differences in human nature and physical constitution". Skilled pickers in India and Egypt also contributed.

The cotton came from the American South and was picked by slaves. After they were freed, many former slaves continued to work on cotton plantations —with low wages and harsh conditions.

What about today?

“The history of the spinneries is also terrible. What did the industrial revolution cost people and the world?” asks Red.

She makes the connection to today.

“What’s it like for people in the textile industry today? We see reports of terrible working conditions for people who sew our clothes, but what about people who harvest the cotton and spin it? Where are the soils that are spread with enormous amounts of poisons and are overused? We don't know anything about that, and we consumers don't care,” Røde said.

After 110 years of operation, Graah's spinning mill and the Hjula weaving mill at Sagene both went bankrupt.

“Perhaps the truth about textile production is that it is simply too cheap. We didn’t pay then for the true costs of what it took to produce garments then, and we still don’t now,” Røde said.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Photo credits:

Spool of cotton and the factories as of today: Nina Kristiansen.

Historical photos: unknown photographer / Digital museum, public domain.

Cotton plantation: Phillip Minnis / Shutterstock / NTB