The strict EAT-diet is supposed to be good for the climate and good for our health. But how did researchers arrive at their recommendations?

The report lacks important information and the EAT dietary advice is based on uncertain models, researchers write in a new review. The EAT experts do not agree.

Dietary researchers agree on one thing, both the EAT-Lancet team and researchers from the research company Epix Analytics: We have to do something drastic with our diets, both because of the looming climate crisis and the harms that can result from a poor diet.

However, professionals don’t agree that the strict EAT diet is the best scientific solution to these problems — at least not when it comes to health issues.

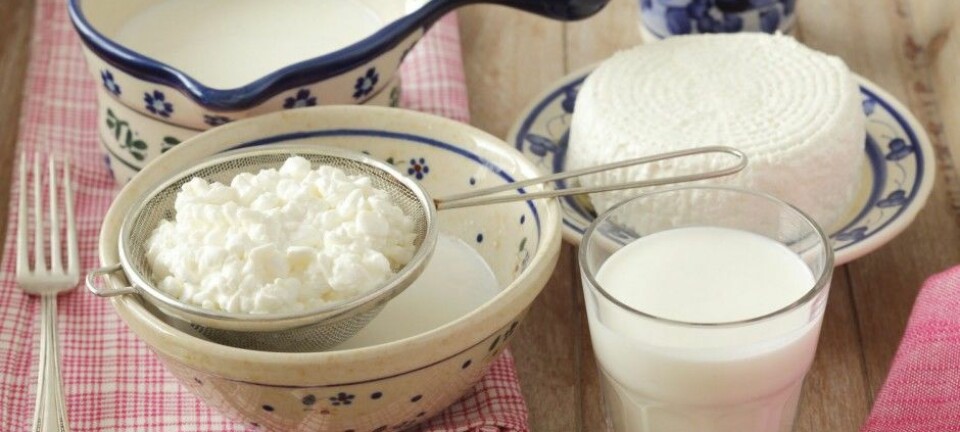

The researchers behind the 2018 EAT-Lancet Commission report suggested a standard diet for the entire population of the globe. Under their approach, half a person’s plate would be filled with vegetables and fruits, while only a tiny corner would contain meat, fish, eggs and milk products. The researchers believe this type of diet could prevent millions of deaths each year.

But it’s not clear how the researchers came up with this diet, and there are some methodological errors in the models, according to researchers from Epix Analytics, who recently wrote about this in the research journal The Lancet.

Norwegian company helped sponsor new review

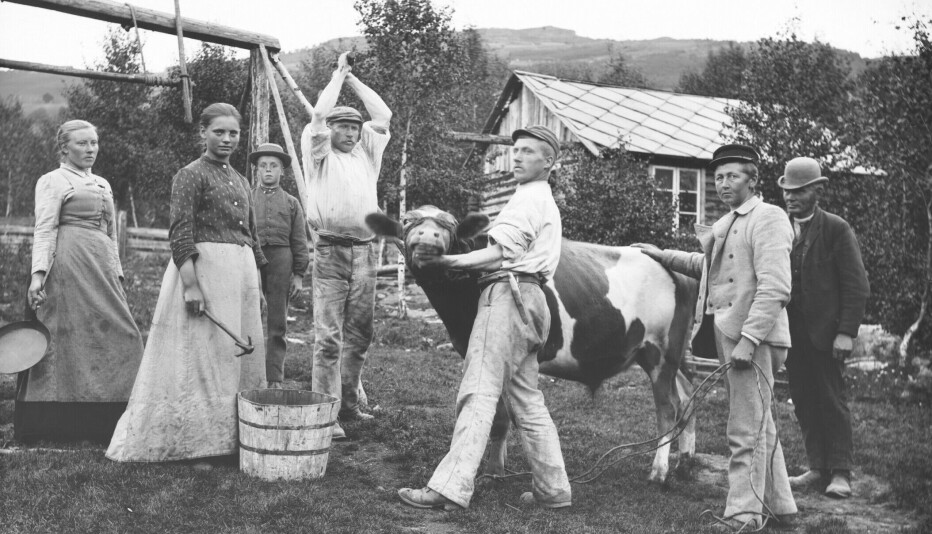

The mission to review the EAT-Lancet report comes, not unexpectedly, from a group of organizations that promote meat and other animal products, including a Norwegian organization called MatPrat, which is supported by the Norwegian Information Office for Eggs and Meat. The name translates as “Food Talk”.

“We at MatPrat /the Information Office for Eggs and Meat have questioned how the EAT-Lancet’s Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems has come up with completely different recommendations in some areas than most other summaries of what is known and dietary advice,” MatPrat writes in an email to forskning.no.

“We have not been able to find out what methods have been used to quantify the diet, or to find a system for the selection of studies that form the basis of the report, and which ones were excluded,” the organization writes.

When MatPrat did not receive a response from the research team behind the EAT-Lancet report, they decided to commission the independent research institute Epix Analytics to go through the methods of the EAT researchers.

As a result, Epix Analytics researchers Francisco Zagmutt, Jane Pouzou and Solenne Costard wrote a critique of the EAT-Lancet report for the Lancet.

Based on a summation of previous research

Much of the criticism levelled by the Epix Analytics researchers relates to the fact that the EAT researchers are not open about how they have arrived at their recommended diet.

Their recommendations are based on a review of research on the relationship between food and health. But that is no simple task. There are an incredible number of individual studies on food and health, and these are also summarized in many other different systematic reviews.

Consequently, it goes without saying that the researchers had to make a selection, screening out the most relevant studies.

But which studies were selected? This is an area where there is room for interpretation.

For that reason, the Epix Analytics researchers say the EAT group should have described their selection process, so that other researchers could assess whether the sample and the criteria were well balanced.

Unclear how EAT researchers selected studies

Zagmutt and his colleagues criticize the EAT researchers for not describing the methods they used. They also find fault with the lack of reflections on which factors might have affected the results.

In addition, numbers used in the EAT report to describe risk don’t always match up with the studies from which they were obtained, Zagmutt writes.

Another point made by the Epix Analytics group is that EAT researchers compared their strict, calorie-specific diet with the diet people have today, when they calculated how many deaths could be avoided with a new diet.

However, when Zagmutt and colleagues did their own analyses of the American population, they concluded that the EAT diet would not save more lives than any other diet with equally few calories.

May not prevent premature death

An earlier study supports this argument.

Anika Knuppel from the University of Oxford and her colleagues ranked the participants in a large study by how close their diets were to the ideals of the EAT diet, and compared this to how good their health was.

It turned out that those whose diets were most in line with the EAT recommendations had a lower risk of heart attack and diabetes, compared to those whose diets were least similar to the EAT diet. But there was no difference in the risk of stroke and no clear link to the risk of premature death.

There are also signs that those who ate most like the EAT diet generally had a healthier lifestyle, Knuppel concluded in The Lancet this summer.

Have now published a description of methods

Researchers behind the EAT report were given the opportunity to respond to the Epix Analytics criticism. In the same issue of The Lancet, Walter Willett, Johan Rockström and Brent Loken write:

“In our report, we were not able to describe in detail the three different methods used to estimate the number of preventable deaths among adults, but these have now been published separately.”

Willett and his colleagues also write that all three analyses, using different methods, produced the same result: The EAT diet could prevent around 11 million premature deaths around the globe each year.

“Zagmutt and his colleagues do not provide any counter evidence,” they write.

Willett also says that they did not include the possibility that people would cut calories in their calculations. If the EAT researchers had assumed that people would eat only enough to maintain a normal weight, then the estimate of how many premature deaths would be prevented would be even higher, they write.

The EAT researchers also received strong support from several Norwegian nutrition researchers earlier this year. The EAT diet is actually astonishingly similar to the Norwegian authorities’ dietary recommendations, they wrote in an op-ed on forskning.no earlier this year.

In another op-ed, Norwegian researchers wrote that the EAT report has never claimed that the EAT diet is the only option for a healthy diet.

Paid for by organizations that promote meat and dairy

It is worth noting that the clients behind the new report are organizations that promote the use of meat, eggs and dairy products — which are precisely the food groups the EAT-Lancet report recommends people mostly cut from their diet.

This in theory should have no effect on the Epix Analytics report. But there are many stories where those who pay for the research have influenced the results of reports they have commissioned.

For example, a client may have formulated the research questions in a way that favours certain results, or they may stop the publication of results or reports they do not like.

More on this topic: Researchers under pressure: “We can't conduct secret research.”

EAT researcher previously criticized for over-simplification

On the other hand, university researchers are also not always without financial, idealistic or personal ties.

Willett, a supporter of plant-based diets, was criticized a few years ago in an editorial and an article in the research journal Nature.

The widely recognized Harvard nutritionist was criticized for running down studies that went against his own lifestyle advice, but at the same time highlighting studies with weaknesses, if the results supported his view.

"It is risky to oversimplify science for the sake of a clear public health message," the Nature editors wrote in their 22 May 2013 editorial.

Nutrition research rife with disagreement

The new criticism of the EAT-Lancet report is just one of a number of professional debates about diet and health.

For example, a debate has long revolved around the health effects of different types of fat.

And recently there was a great commotion when an expert group reported that people don’t need to cut red meat from their diets to be healthy.

One of the reasons for all the back-and-forth arguments in nutrition research is that the results these recommendations are based on often contain uncertainties.

Dietary research is largely based on population studies, where researchers survey the lifestyles of a large group of people. They then watch how the health of their study participants changes over time.

For example, it may seem as if people who eat a lot of meat, on average, die earlier than those who eat only a little.

But the problem with studies like these is that that they say nothing about what leads to what, and that results can often be affected by misreporting and underlying factors. Are people honest about how much meat they eat? And is it the meat that kills people, or do meat lovers generally have a more unhealthy lifestyle than people who eat the most plant-based foods?

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

F. J. Zagmutt, J. G. Pouzou, S. Costard, The EAT–Lancet Commission: a flawed approach?, The Lancet, September 2019.

W. Willett, J. Rockström, B. Loken, The EAT–Lancet Commission: a flawed approach? – Authors' reply, The Lancet, September 2019.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this story on forskning.no