Does fertility decline after age 35?

There is still a good chance of getting pregnant in your late 30s. But the risk of miscarriage and complications increases with age.

Some women put off having children until they are well into their 30s, but how long can they wait?

In an article at The Conversation, researcher Karin Hammarberg writes that women's fertility does not suddenly plummet when they turn 35.

She has the impression that many people think that the chance of getting pregnant takes a serious dive when a woman turns 35. But that is not the case. Women still have a good chance of conceiving after that. The decline is gradual, but accelerates from the mid-30s on.

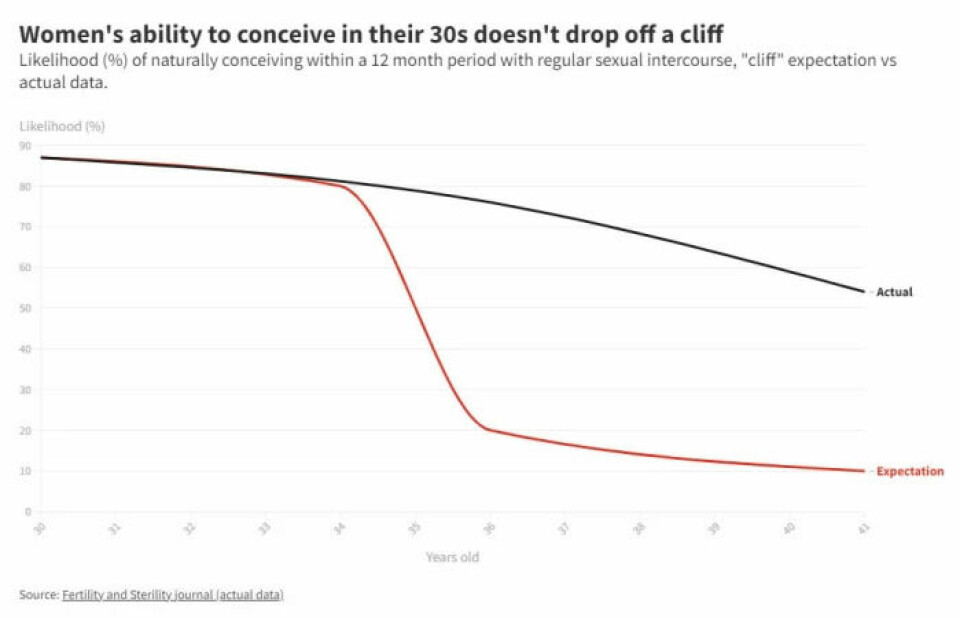

Hammarberg shows a graph that looks more like a gentle slope than a cliff.

Most women conceive within a year

The graph is based on a study published in Fertility and Sterility from 2016. American researchers followed approximately 900 women between the ages of 30 and 44 who were trying to conceive.

Within a year, 87 per cent of the women between the ages of 30 and 31 became pregnant. The conception rate for women aged 36 to 37 was 76 per cent.

Among women aged 40 to 41, just over half conceived within one year.

The study does not state how many women miscarried.

A similar study has been carried out in Denmark and was published in Fertility and Sterility in 2013.

This study showed that 87 per cent of women aged 30 to 34 became pregnant within a year. Conception was 72 per cent for women who were between 35 and 40 years old.

The researchers found that the chance of conceiving peaked at age 30 – or at age 28 for women who had not had children yet.

Individual differences

Siri Eldevik Håberg is a researcher at the Centre of Fertility and Health at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

She agrees that the decline in fertility occurs gradually.

“Women’s fertility is fairly stable until they are around 30, and after that changes occur that cause fertility to decline altogether,” says Håberg. “It drops more steeply once you’re 35, but all the biological processes begin before that. Biology works in gradual ways.”

She points out that there are individual differences.

“For some women, the decline begins earlier than for others. Some medical conditions can bring on an early decline in fertility and early menopause. But even within the normal range, there are big variations in when fertility begins to decline,” Håberg says.

When does the risk of miscarriage increase?

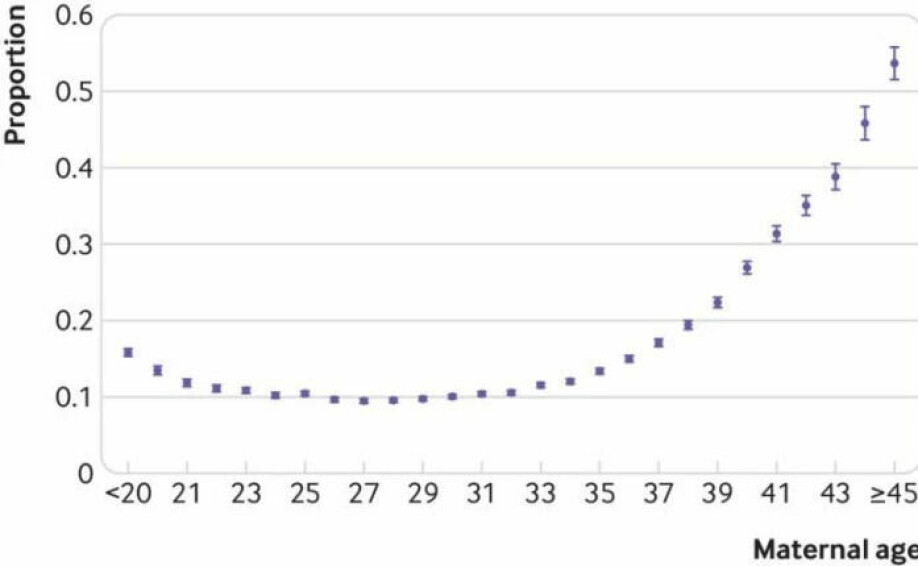

Some good studies have been carried out using Norwegian data that show that age and miscarriages are linked, says Håberg.

“The risk is lowest until you are about age 30. Then it starts to increase through your 30s. The curve becomes steep in the late 30s. It's one thing to have problems conceiving, and another thing to carry a pregnancy to term. That likelihood also decreases with age.”

A study on the topic, based on Norwegian data, was published in 2019 in the journal BMJ. Håberg was involved in the study.

The researchers looked at more than 400,000 pregnancies among Norwegian women.

One in ten women aged 25 to 29 had pregnancies that ended in miscarriage.

For women aged 38, two out of ten pregnancies ended in miscarriage.

The risk increased even more strongly after that. Half of the pregnant women over 44 miscarried.

Historical study of the time before birth control

Women's birth rate from the time before contraception was available can give a picture of natural fertility and when it declines.

In a 2014 study, researchers used records of births from the 17th to 19th centuries in several countries. The study included 58,000 women. The researchers looked at how old the women were when they had children and when they had their last child.

From this data they were able to build a picture of when fertility declined.

The vast majority, 98 per cent, had more children once they turned 20 years old. Most of them, 93 per cent, also had more children after they turned 30.

It didn't stop there – 88 per cent had more children after they turned 35, and 80 per cent after the age of 38.

Then the numbers start dropping faster. 50 per cent had more children after they were 41, but only ten per cent had children after age 45. Almost none had more children after they turned 50.

Uplifting

The study provides an encouraging picture for women who are about to start trying to have children late in the game.

‘Our findings challenge the unfounded pessimism regarding the possibility of natural conception after the age of 35,’ the researchers wrote.

At the same time however, the findings also show that it might be a good idea to speed up.

If you turn things around, the study suggests that there is a 12 per cent chance of not having more children after you turn 35, 20 per cent when you are 38, and 50 per cent when you are 41.

Studies based on historical data like this one were criticized in an article in The Atlantic in 2013.

Better health services and food access today may mean that the figures are not completely comparable. It may also be that the effect of a long marriage and thus less frequent intercourse comes into play. Couples with many children may have tried to avoid feeding more mouths.

Why is fertility declining?

What are the reasons for fertility declining with age?

Håberg finds this an exciting topic and says that a lot is still unknown.

Part of the explanation is that you are born with a certain number of egg cells. No new ones are produced.

“The number of eggs you’re born with are the number you have. That number decreases steadily from childhood onwards,” says Håberg.

A baby girl is born with about one million eggs. When she reaches puberty, she has around 300,000 left.

Each menstrual cycle releases one egg.

Do you enter menopause because your eggs are used up?

“It’s not that you’ve used up all the eggs, but the eggs deteriorate and die in the ovaries as you get older,” says Håberg. “You have a lot more eggs than you need for a lifetime. But by a certain age, very few egg cells are left.”

More eggs with mutations

As you get older, the quality of the eggs declines, says Håberg.

“The chance of genetic errors increases with age, and this helps to explain why miscarriages increase. Mutations in the sperm also play a role. Research has shown that sperm quality also decreases with age,” she says.

It becomes more difficult to conceive over time, partly because more fertilised eggs are not viable.

“The occurrence of genetic mutations in the embryo, meaning changes in the DNA, also increases with age. This means that it can take longer to conceive when fertilised eggs aren’t viable,” says Håberg.

According to Hammarberg's article in The Conversation, approximately 20 per cent of eggs have the wrong number of chromosomes. This proportion increases as women age. When such an egg is fertilised, it usually leads to an early miscarriage.

Hormonal changes also occur, which can make it more difficult to have children with increasing age, Håberg points out.

It also becomes more difficult to succeed with assisted reproductive treatment at higher ages.

“Another explanation could be that you get various other diseases over time that can affect fertility. Weight often increases with age and can contribute to reduced fertility,” says Håberg.

Low chance of child having deformities

Older first-time mothers run an increased risk of complications such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, as well as longer labour and caesarean section being necessary, according to the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

The chance that the child will be born with deformities or chromosomal defects also increases with older age.

But the chances are still far greater that the child will not be born with such conditions.

“Many of the conditions are rare. The risk is greater. But if you manage to conceive and carry a pregnancy to term, then the vast majority of children are healthy,” says Håberg. “Although complications during pregnancy and at birth are much more common in older pregnant women, most pregnancies go quite smoothly.”

Approximately 2.7 per cent of babies are born with abnormalities, including conditions like clubfoot, cleft lip or palate, heart defects or chromosomal defects.

According to a Norwegian study, the risk of the child having a deformity increases starting around age 40. The risk then rises sharply in the 45 and over age group.

The 45 and over group had a 3.5 per cent chance of having children with congenital abnormalities. Parents between 30 and 34 years old had a 2.8 percent chance of the same.

The chance is thus still far greater that babies are born without abnormalities than with, regardless of age.

References:

Anne Z. Steiner & Anne Marie Z. Jukic: Impact of female age and nulligravidity on fecundity in an older reproductive age cohort. Fertility and Sterility, 2016.

Maria C Magnus, Siri E Håberg et.al.: Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register based study. BMJ, 2019.

Kenneth J Rothman et.al.: Volitional determinants and age-related decline in fecundability: a general population prospective cohort study in Denmark. Fertility and Sterility, 2013.

Marinus J.C. Eijkemans et.al.: Too old to have children? Lessons from natural fertility populations. Human Reproduction, 2014.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no