Norwegian researchers are developing a new method for detecting breast cancer

Artificial intelligence can help speed the detection of breast cancer. Urgent examinations will be undertaken sooner.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, both worldwide and in Norway. The earlier the cancer is detected, the more people survive.

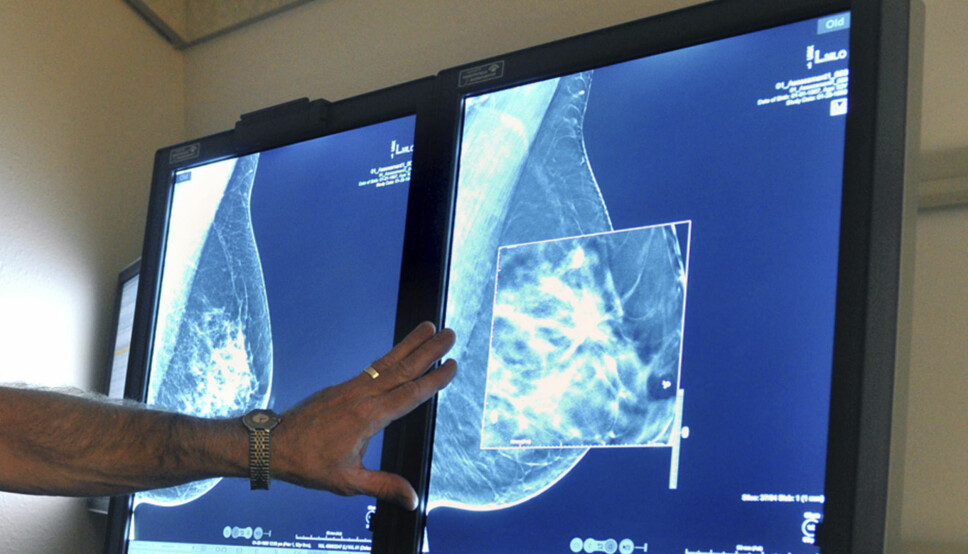

Mammography has saved many lives. But it can be difficult for radiologists to interpret the images, and the technology requires a lot of resources from the health care system.

Promising recent studies now suggest that artificial intelligence can help.

Artificial intelligence as good as a radiologist

Swedish researchers have recently published a study that shows that the best algorithm is as good as the average radiologist in detecting breast cancer, according to a press release from Karolinska Institutet.

In January, it became clear that researchers from Imperial College London and the IT giant Google have developed artificial intelligence that was better than six radiologists, according to an article on the BBC website.

Difficult to distinguish

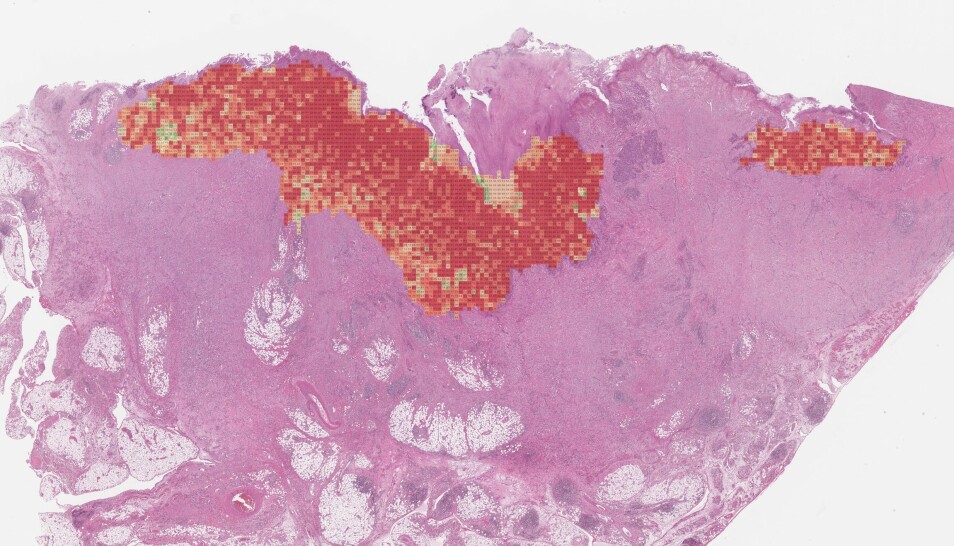

Norwegian researchers are also studying how artificial intelligence can help radiologists, who often struggle to distinguish between cancer tissue and healthy tissue.

Line Eikvil is a researcher at the Norwegian Computing Center who is involved in a project led by the Cancer Registry of Norway. The project is developing an algorithm that uses artificial intelligence to decipher the images from a breast cancer screening.

Norway has had a mammography programme for more than 20 years. All women between the ages of 50 and 70 are called in for screening every other year.

This means that researchers who want to train artificial intelligence to distinguish between healthy and diseased breast tissue have access to a lot of data.

“We have a method up and running now. But we are still in the process of collecting enough data on breasts that are cancerous. The vast majority of women who are screened are fortunately healthy. That means there’s actually not a lot of data on cancer cases,” she says.

Data from other countries

When the researchers initiated their project in 2018, the plan was to use only Norwegian data.

“Since we started the project, other groups have done similar studies elsewhere in the world. That means we can combine our data sets with others,” says Eikvil.

Artificial intelligence requires lots of images to learn.

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden have compared three algorithms in the study mentioned above. The method that had access to the most data for learning was the best at detecting cancer.

Deep learning

The approach is based on what is called deep learning.

This involves training computers to recognize something in an image that represents what you want them to find, says Eikvil.

“We’ve traditionally done this by extracting selected properties from the image. If you are going to learn how to distinguish between bananas and oranges, you can calculate properties that depend on the colour and shape of the fruit. However, when reading a murky x-ray, it’s hard to determine which properties distinguish cancer from healthy tissue,” she said.

With deep learning and lots of data with which to train the computer, it can learn what separates healthy tissue from diseased, and can get better and better, she says.

Not afraid of becoming unemployed

Today, two completely independent radiologists look at a mammogram after a woman’s screening.

If there is a large discrepancy between their two conclusions, they meet and decide on an answer.

The discussion of artificial intelligence is often centred around the negative aspects of this technology. People are afraid that computers will take over their jobs.

Helga Brøgger is not worried about becoming unemployed, however.

As head of the Norwegian Radiological Association, Brøgger points out that AI is just a tool for humans to use.

Brøgger hopes that artificial intelligence will mean faster diagnoses from mammograms.

That will allow urgent examinations to be prioritized, so that they are read earlier.

“It’s fun to be a radiologist today, but it will be much more fun once we start using artificial intelligence. Then we’ll be able to free up time and use that time instead with our patients and on difficult cases. We’ll also have more time to consult with each other,” she said.

Depends on people

Although there has been a lot of research showing that artificial intelligence can diagnose diseases, it will take time before this is routine, Brøgger said.

“Where large data sets are available, such as with mammography, I think we will see good tools in clinical use soon,” she said. “When it comes to smaller patient groups, where there are not as many patients and data, it will take longer before this technology finds its way to hospitals.”

Once the algorithms are ready to use, the professional community will still need to address a number of questions, she says.

“Will we get the same results at different hospitals, with different algorithms and a different group of patients? How do we integrate these tools into a hospital’s existing digital systems? Who is responsible for the decisions these tools make?”

Must work closely together

Eikvil and Brøgger say that artificial intelligence requires close collaboration between the technologists who develop the algorithms and the healthcare professionals who will use them.

“If we can build our expertise, we’ll have a better understanding of the approach and what it is good or bad at,” says Eikvil.

Brøgger agrees.

“Collaborating with technologists makes us better able to understand the technology and use it in our computer systems. We need to learn how to use these solutions so that we’re confident we’re offering sound services and that we can explain how decisions are made to our patients,” she said.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

———