Faecal transplantation helped many with IBS

A new Norwegian study reports that many patients treated with faecal transplantation felt completely healthy after treatment. But everyone in the study were given bacteria from a single donor with a special gut flora. So what do the results mean for faecal transplantation in general?

Marte Rykke Halstensen was astounded by the changes she experienced after faecal transplantation.

“After a week, I woke up with this incredible feeling that I didn't actually notice my stomach. I could have never imagined this would be possible,” she says.

For most of us it might seem self evident that we don't think about our stomachs first thing in the morning.

But Halstensen had been struggling with irritable bowel syndrome, IBS, since childhood. Normally, she would always wake up with stomach pain and discomfort. Often the pain would wake her several times a night as well.

Intestinal bleeding

Irritable bowel syndrome is a disorder that affects about ten per cent of the population. The symptoms include pain, bloating and abdominal cramps. Some, like Halstensen, struggle with constipation.

“I could go two to three weeks between each visit to the toilet,” she says.

“I got tears on the inside of my intestines and bled from my rectum. During the worst periods, I vomited and vomited, and was completely drained of energy.”

Other people with IBS suffer with diarrhoea. After a meal, abdominal pain sets in, and then it’s best if a toilet is just a few steps away. For those who are severely affected, it can be difficult to leave the house.

IBS is not dangerous in the sense that it can kill you. But the suffering can greatly affect your quality of life. Having a normal social life becomes difficult, and in the worst case, it becomes impossible to get a job or education.

The doctor thought it was in her head

Although IBS is very common, doctors and scientists have known little about what causes the disorder. And they have had little to offer to help people with this problem.

Halstensen went in for many examinations, but the doctors couldn’t find anything wrong. She herself thought that food was making her sick, but she couldn't figure out exactly which foods were causing problems.

“The doctors thought it had to be something mental — that it was in my head. It was devastating, because I felt mentally strong. And mental problems don’t run in the family — although bad stomachs do.”

Halstensen was referred to therapy, but the treatment did not make her better.

Intestinal imbalance

Gradually, however, Halstensen began to notice changes in the doctors themselves.

In recent years, researchers and the medical community have learned more and more about IBS. For example, a decade of studies have documented that many people with IBS get better by avoiding foods that contain certain types of carbohydrates, called FODMAPs.

These are substances that the gut cannot absorb, but which feed the flora of microorganisms in the large intestine.

A great deal of research suggests that imbalances in the gut bacteria can play a significant role in many IBS disorders.

This in turn has given clinicians new ideas about how the disease can be treated.

One of these ideas was to transfer good gut flora from a healthy donor to patients, in the hope that the new bacteria will establish themselves and replace the unfavourable mix that was there before.

In 2017, researchers studied exactly this type of stool transplant at Stord Helse Fonna Hospital, on the southwest coast south of Bergen.

Inserted faeces into the intestine

“We were only supposed to have 100 patients in the study,” says Professor Magdy El-Salhy at Health Fonna and the University of Bergen.

“But there were so many more who wanted to participate. We had to apply for ethical approval to increase the number,” he says.

In the end, 164 people were included in the study, among them Marte Halstensen.

“I was told that there was a waiting list, but then someone withdrew and I was able to join,” she says.

She felt like this was her last hope. Halstensen had improved a little when she cut food with a lot of FODMAPs from her diet. But she still felt so poorly that she considered whether she should apply for a partial disability allowance.

“I really have a lot of capacity for work, so this was a bad feeling,” she says.

But then came the trip to the hospital at Stord. First she was given lots of information, preliminary tests were taken and she had to fill out standardized forms to identify IBS symptoms, fatigue and her quality of life.

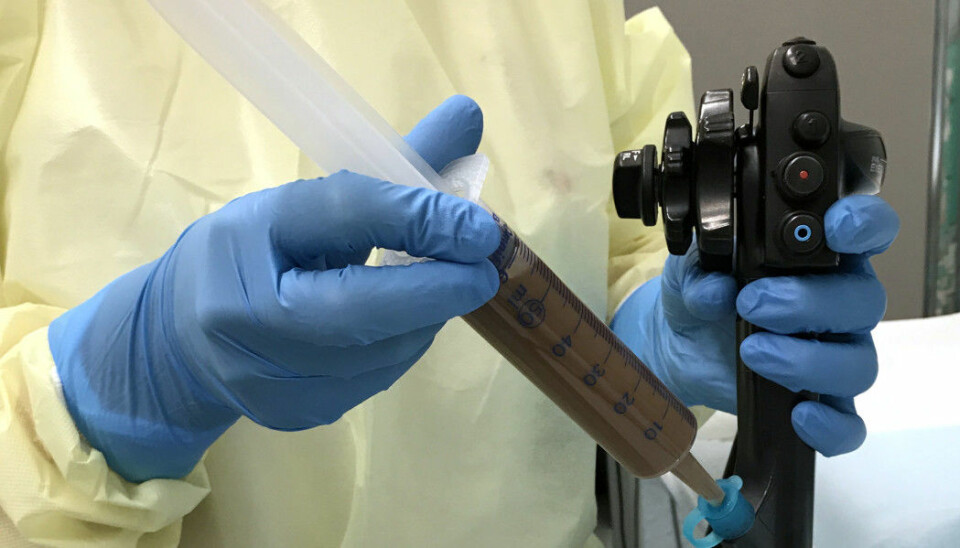

Then Halstensen had to swallow a tube, which was passed down through her stomach and into the upper part of her small intestine. The researchers then injected a stool sample through the tube into her gut.

Participants in the study received either 30 grams or 60 grams of stools from a donor, or just a sample of their own stools. Halstensen did not know what she was given. Neither did the researchers who analysed the results.

Healthy now

It doesn’t feel very good to have a tube passed into your stomach. But the manoeuvre was over quickly and Halstensen had no problems with the insertion itself.

However, the days that followed were tough.

“I was really in a lot of pain. I was nauseated and unwell, thinking this was not going to go well.”

But then came that unforgettable morning, the one where she woke up and amazingly didn’t notice pain in her stomach.

Today she describes herself as healthy.

“From not being able to eat anything, I can eat everything! Lots of bread and onions and all kinds of fruit. I couldn't eat any of it before,” she says. “I live just like everyone else, and have no pain or discomfort.”

Nearly 90 per cent improved

"Almost 50 per cent of the patients in the study became completely healthy," says El-Salhy.

He has now presented his results at a professional conference. An academic article describing the study will soon be published in the journal Gut.

The results showed that almost 90 per cent of patients who had received 60 grams of stool from the donor had improved. Over 75 per cent of those who were given 30 grams from the donor also experienced improvement. The same was true of just under 25 per cent of patients who received a placebo — that is, their own stools.

The same trend was observed in the responses to the questionnaires.

But not everyone got better. Some experienced no improvement. Others got better, but were not completely healthy.

"Lars" was one of them.

Got IBS after surgery

Lars is a busy family father in his forties. He does not want to use his real name, but is happy to talk about the study and how having stomach trouble can affect a person’s life.

It all began with surgery and several rounds of antibiotics a few years ago. After this, Lars began to experience stomach pain after meals.

Severe chest pain made doctors suspect stomach ulcers. Medical examinations showed no ulcers but an H. pylori bacterial infection. This led to a new round of treatment with two types of antibiotics and antacids.

After that, his stomach was worse than ever.

But Lars did not have constipation — he had the opposite problem.

Better, but still has problems

“I would get intense pain after eating. Then I had to be near a toilet,” he says.

This isn’t great when you have a job with lots of meetings and activities involving other people. Or for that matter, when you want to go for a long walk with the dog.

“There could be days where I was good, but then there were periods that were not so good,” he says.

Unlike Halstensen, Lars hadn’t had much contact with the health care system for his stomach ailments. But with time, his stomach problems happened more and more often. That's when he joined El-Salhy’s study, as one of the last participants.

Lars did not recover. But he thinks he's better.

“I don't get the major pain I used to have anymore, and I don't always have to be so close to the toilet. But I still have periods when I have problems and there are many things I can't eat,” he says.

He typically has problems while on holiday, when it’s not as easy to know what’s in the food he’s eating.

“But I’m not person who’s looks for problems. Instead, I try to be positive, make things work and live normally.”

Lars would have liked to be given the opportunity to get another, larger dose of faeces from the donor. But for the moment, he can only get that treatment as part of a medical study.

Does not necessarily apply to everyone with IBS

If additional studies confirm these initial results, El-Salhy envisions IBS patients being treated with repeated doses, if the initial effect is not good enough or decreases over time.

“It would not take huge resources,” he says.

Especially in comparison to what the disease requires when it is untreated.

“IBS patients are more common in the doctor's office than people with diabetes, asthma or high blood pressure. The patients are exhausted and sick. It affects young people at a stage in life where they are studying or are about to start a family and a career,” he says.

El-Salhy believes better treatment will save both money and suffering.

But there is still much that is not known about faecal transplantation.

“The participants in the study were patients who did not get better by changing their diet,” El-Salhy says.

“That means we can’t say that these result apply to everyone with IBS. At the same time, there is nothing to suggest that it should not work.”

Promising results

Rasmus Goll at UiT The Arctic University of Norway is also conducting research on IBS and faecal transplants.

“First and foremost, I see this as a confirmation of previous studies,” he says.

Goll says that five small studies have been done in the past, with striking results. Two studies in which the stools were given in capsules that the patients swallowed showed no improvement. In one of the studies, the placebo group actually came out better.

But three other studies, in which the donor samples were inserted directly into the gut, have shown promising results. Goll himself was behind one of these studies. But the results of the new study by El-Salhy and colleagues show a significantly better effect.

“This study is also the largest of its kind so far, which means its conclusions are somewhat more concrete,” Goll said.

Super donor

El-Salhy believes the study showed such good results because the donor that was used is what he calls a super donor, with a very special gut flora.

“The donor is a 36-year-old athlete. He does not smoke, takes no medication and has only been through three antibiotic courses in his whole life. This is unique,” El-Salhy says.

“He was born vaginally and was breastfed as a child."

All of these factors promote a healthy gut flora.

The man eats a normal Norwegian diet, but with a lot of protein and a lot of fibre. In addition, he takes many different supplements, which is common in the sports world.

Tests have shown that the intestinal flora of this donor contains high or low levels of certain bacteria, compared to a sample of 165 other healthy people, El-Salhy says.

He says that studies on faecal transplants for other bowel diseases have shown that some donors appear to be clearly better than others. In addition, different patients may need different donors.

El-Salhy and his colleagues will start new studies to test the effect of different doses and different donors, in order to determine what gives the best results.

Don't know what good gut flora is

Goll, on the other hand, is not convinced that the super donor is behind the El-Salhy’s results.

“It’s impossible to say, since all the participants in the study received stools from the same donor,” he says. Then you have no one to compare with.

Goll is also sceptical as to whether today's tests of intestinal flora are good enough to say anything meaningful about the bacteria in either the donor or the patients.

“The tests only scratch the surface,” he says. “The gut flora contains perhaps 1200 different types of bacteria, while the tests measure 60-70 types.”

Admittedly, these are bacteria that can play important roles. But for now, too little is known about what characterizes a good and a bad gut flora, the researcher says.

Placebo effect was limited

Goll believes that some of the reason for the clear results from El-Salhy’s study is because the placebo effect was quite small, compared to previous studies.

Most previous studies of treatment for IBS have also shown great efficacy in patients receiving a placebo. Goll believes there are two reasons for this.

One is that researchers often recruit patients with severe symptoms. That probably means they have included many patients who are quite ill. Because symptoms of the disease fluctuate, many of these study participants will get better on their own, regardless of treatment.

The second reason is that patients with IBS are often not taken seriously. They are often told by doctors that there is nothing wrong with them. But the problems remain the same, and the patients are left without help. This can be so disappointing and frustrating that it makes people worse.

“They can get better just by joining a study where their illness is acknowledged,” says Goll.

He believes this may help explain why El-Salhy's study showed so little placebo effect.

“The area around Bergen is very good at treating people with IBS in the first place,” he says.

Patients feel like they are taken seriously, while at the same time they aren’t made anxious that they have a serious illness. That reduces the placebo effect to a very great extent, Goll says.

The X-factor and different causes

Since we know little about what really happens in the gut after a transplant, it’s reasonable to wonder whether there are other explanations for El-Salhy and his colleagues’ results.

In this study, for example, faeces were inserted at the top of the small intestine, while other studies have inserted faeces from below, into the large intestine. This might be part of the explanation.

There may also be “x-factors” that researchers are unaware of. The intestinal flora, for example, contains much more than bacteria. Maybe fungi or viruses play a significant role?

Another issue is that there are likely completely different causes behind the symptoms of different IBS sufferers. For some, the disease may be due solely to an imbalance in the gut flora. In others, stress may play a major role.

This is probably partly why one type of treatment may work quite differently in two patients.

A big new study next

All of this suggests a need for basic research on what is happening in the gut and the body, and on specific treatments, such as faecal transplantation.

Goll can tell us that he and his colleagues at UNN Harstad and UiT The Arctic University of Norway have just received support for a large study on faecal transplantation.

In early 2021, they will start recruiting as many as 400 patients at four different centres around the country. Participants will be treated with faeces from several different donors.

This study will be large enough and monitored well enough so that it can answer the question as to whether the health care system should treat people with IBS with faecal transplants or not, says Goll.

Hope others get the same opportunity

Study participant Halstensen hopes that faecal transplants will be available as soon as possible. Partly because she fears what will happen to her if the effects of the faecal transplants she received diminish over time, and partly because she would like to see others given the same opportunity as she was given.

“It’s an invisible illness, and you can be very frustrated by not being understood. You just want someone to help you,” she says.

“After I became a mother, it was terrible. I felt so awful and didn’t have enough energy to make it through the afternoon. It's painful when your two-year-old child has learned to say ‘Mom has a sick stomach and needs to rest’," she says.

Suffering can interfere deeply with the important things in life.

“I think many people find it very difficult to be intimate. It's hard to have people close to you when you're in pain and feeling awful. It hurts and can have major consequences,” she says. “Now I'm restlessly waiting for treatment to be available to other people who are ill.”

Reference:

M. El-Salhy et.al: Faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in IBS using a super-donor: A randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled study, presented at United European Gastroenterology Week in Barcelona, 2019.

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

———