Tuberculosis and cholera gave us sewage systems and posters against spitting. What will the coronavirus leave us with?

Will we ever be able to hug again?

Before the pandemic, we shook hands with new acquaintances and shopped at the grocery store, unfettered by plexiglas.

The pandemic is going to change us forever, although no one knows quite how yet.

But perhaps a look at previous epidemics and pandemics can provide some clues?

“Previous epidemics, such as tuberculosis and cholera, changed Norwegian society in a number of ways,” Professor Geir Sverre Braut said at a recent seminar at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences.

Posters about spitting in public places

Tuberculosis was to blame for about every fifth death in Norway around 1900, and around 60 per cent of the dead were under 30, according to figures from Statistics Norway.

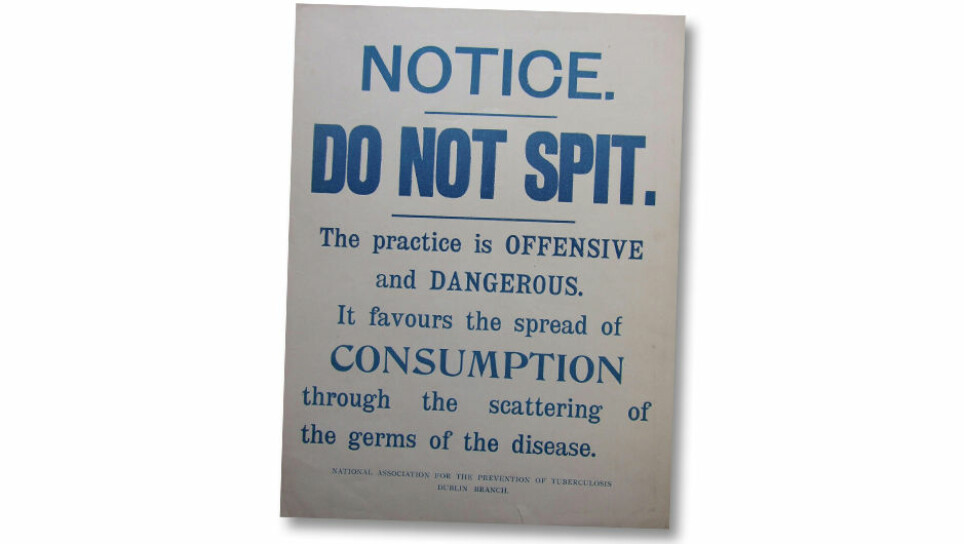

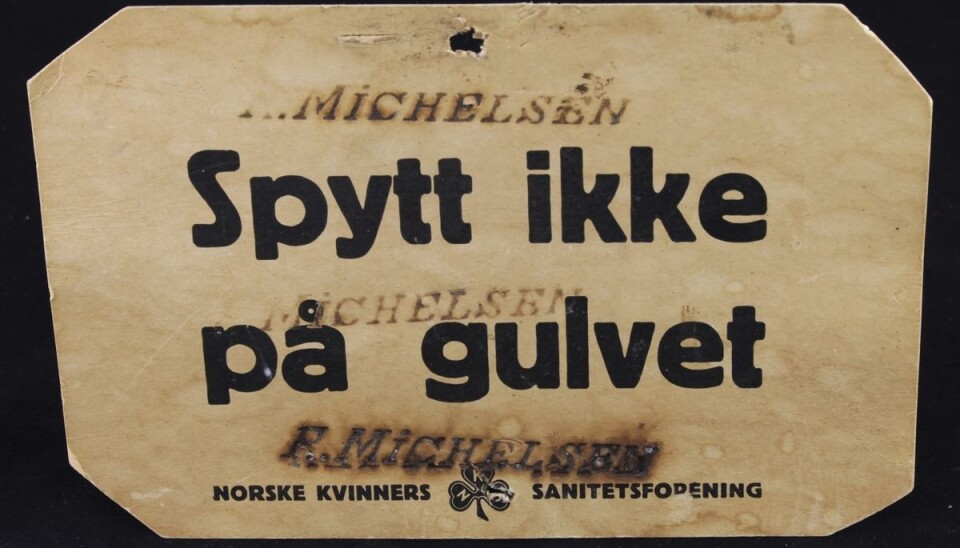

One of the infection control measures at the time, in addition to isolation and quarantine, was an informational campaign, in the form of posters designed to keep people from spitting. They were hung in public offices, in churches and on the street.

It said "Don’t spit in the church" or "Don’t spit on the floor. Don’t cough on anyone.” Preferably with an exclamation mark at the end.

“The tradition of spitting probably wasn’t completely controlled, however,” Braut said to sciencenorway.no.

Widespread culture of spitting

It’s unlikely that anyone would spit inside a church or anyone's house today. But people did in the past, especially people who chewed tobacco and smoked. After they had chewed tobacco for a while, the nicotine made them salivate so they needed to spit.

If the saliva also contained the tuberculosis bacteria, it could have a dramatic outcome. Tuberculosis was spread via air and infectious droplets, like the coronavirus.

“So the spitting posters were an attempt to reduce the bacterium's free flow in public spaces,” Braut said. “This is probably one of the reasons why we don’t spit indoors today.”

Drinking water, sewage treatment

We can also thank previous epidemics, especially cholera, for bringing widespread sewage treatment to Norway.

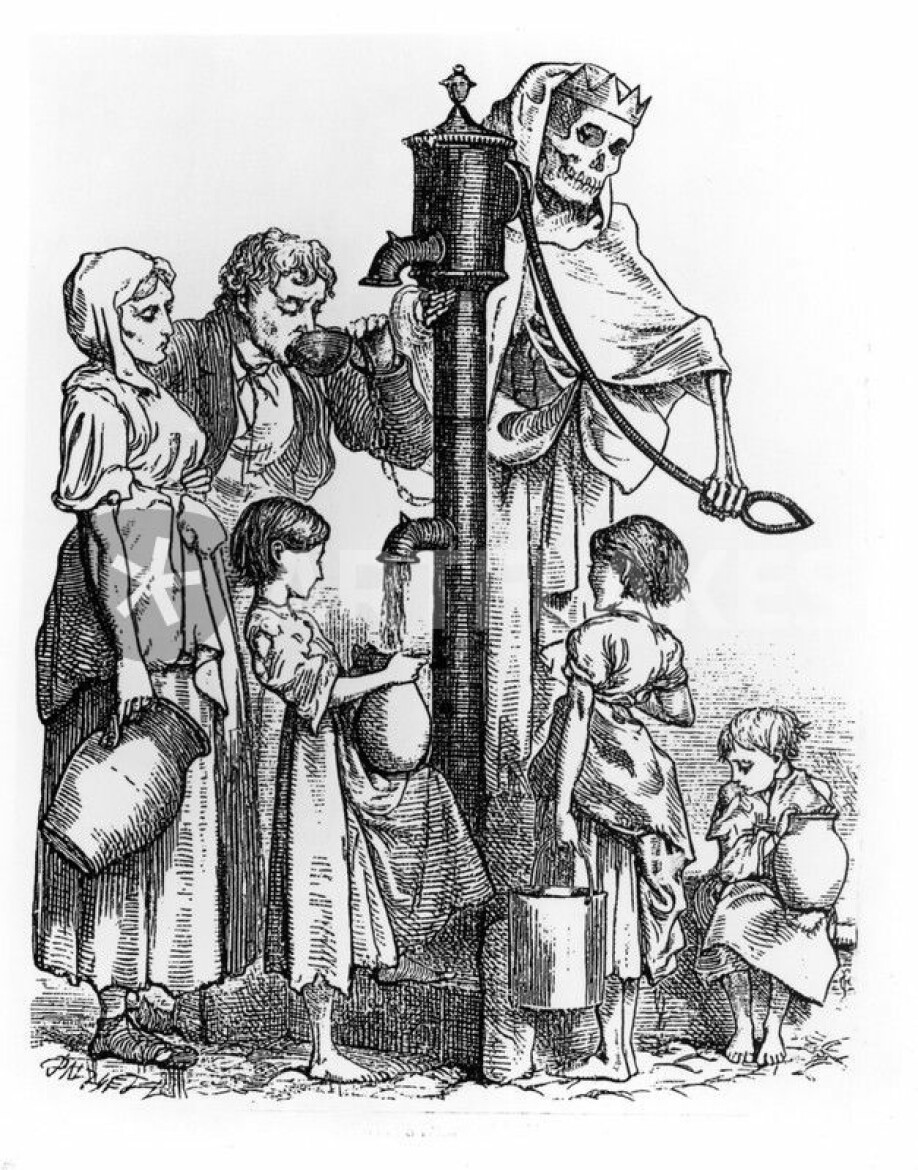

Cholera came to Europe in 1817 and to Norway in 1832. The largest outbreak occurred in 1853, when about 2500 died in eastern Norway, almost 1600 of them in the capital Christiania (now Oslo).

A quarantine station was built on Odder Island in Kristiansand, near the southernmost tip of Norway, where people arriving by ship had to stay for a certain period before they could go ashore.

"The entire development of the sewerage system in Europe took place as a result of cholera in the middle of the 19th century," says Braut. “This had an enormous effect.”

Norway’s efforts to build sewage systems also got a real boost after the British found out that the infection was transmitted through the drinking water — even though this hadn’t been a source of infection in Norway at that time.

Hand washing in maternity wards

Infectious diseases have also affected the practices we still use today in the health care system.

The Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis discovered, among other things, that it was possible to stop puerperal fever in maternity wards by introducing proper hand washing for staff who worked there.

“He bears a lot of the responsibility for today’s hand-washing routines,” Braut said.

“Infectious diseases have been responsible for providing us much of what we know today as good infrastructures and living habits,” Braut said.

When did we start hugging each other?

Ole Georg Moseng, a history professor, also participated in the seminar.

He says that the generation he belongs to — people who were born in the late 1950s — were the first to start being more relaxed about closer physical contact. Until then, people were still concerned about hygiene and keeping their distance due to the experience of tuberculosis.

“It was our generation that started to hug each other in the way we do today,” he said. “But we may have to change that a bit now.”

“My generation was also the generation that drank from each other's cola bottles because the doctors had come to the conclusion that we were actually quite invulnerable to bacterial infections,” he said.

This was also a time when people were vaccinated against viral infections.

Engineers ended cholera

“What we know about infection has been with us for the last 400 years,” Moseng said at the seminar.

And it hasn’t been medical science that has gotten us through these difficult times.

After the devastation caused by the cholera outbreak, it was the people who knew about safe water supplies and who understood the necessity of sewage systems that saved society.

“It was engineers who helped eliminate cholera from Europe, not medicine,” Moseng said.

When it came to tuberculosis, the authorities provided general rules of conduct similar to those we have today.

“Tuberculosis ended because society became increasingly prosperous. Prosperity meant that people could stop living jammed into an apartment, sharing a single bathroom, and with everyone sleeping in the same bed,” Moseng said.

“The major pandemics have been fought without the benefits of medical science,” he said.

What will change after COVID-19?

Previous pandemics have thus affected both social structures and the way we behave.

So what will change after the coronavirus pandemic?

Geir Sverre Braut, the community physician, thinks we will most likely start shaking hands again.

“It’s human nature to want to have some form of physical greeting. At some point, I think it will come back again,” he says. “But it’s not certain that our habit of hugging people will.”

Protect customers and store employees

What he thinks has come to stay, however, are the plexiglass dividers in stores.

“I remember the railway stations in the 1960s and 1970s, when there was glass between the clerk and the customers,” he says. “We had the same in bank branches in the 1970s. When I studied at the University of Oslo in 1974, my bank Kreditkassen had glass between employees and the customers.”

And it wasn’t bulletproof glass, he points out. It was there for infection control.

“This stopped in the 1990s because we as a society wanted more openness. And in the enthusiasm for a more open society, we got rid of these kinds of things. And now we are suddenly back to where glass between customers and store employees is on its way back again,” he said. “I think that is something we will continue to see.”

Braut also believes that people will continue with thorough hand washing in the years to come.

“We in the health care system have been very focused on the importance of hand washing for the last hundred years. But most people have had a slightly more relaxed relationship to this,” he said. “I think many have come back to this now, and I think it will continue.”

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no