Prostitution in old Oslo

Prostitution was illegal in Norway at the end of the 1800s but allowed in Oslo as long as the women submitted themselves to mandatory medical scrutiny. A new exhibition documents the lives of these women.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

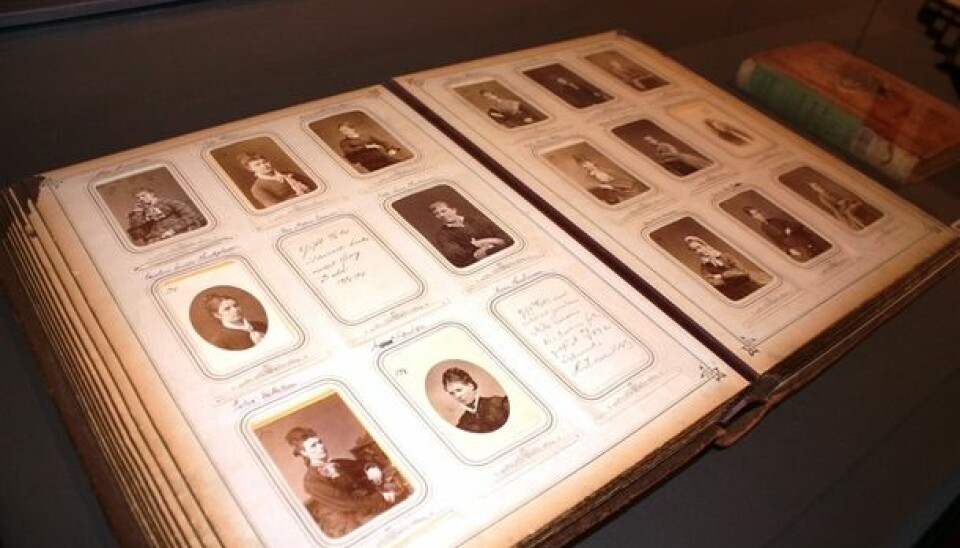

They look like bourgeois ladies, posing on chairs with fashionably arranged hair and their bustle gowns – but they are not high class gentlewomen.

The photos are from an album dated 1900 and it was the vice department of the police in Kristiania (Oslo) which kept official tabs on these women.

They were prostitutes.

An exhibition of paintings by Christian Krohg (1862-1925) titled Captivating Images has opened at the National Gallery in Oslo. Here, curators Vibeke Waallann Hansen and Ellen Lerberg are enlightening the public about prostitution in Christian Krohg’s Kristiania, including why this bohemian artist and others reacted so strongly to these women's plight.

Established in the trade

“Once the women started as prostitutes they would be fitted with beautiful gowns as work clothes, wear makeup and sport high hairdos. We see this in the Albertine picture too,” says Hansen.

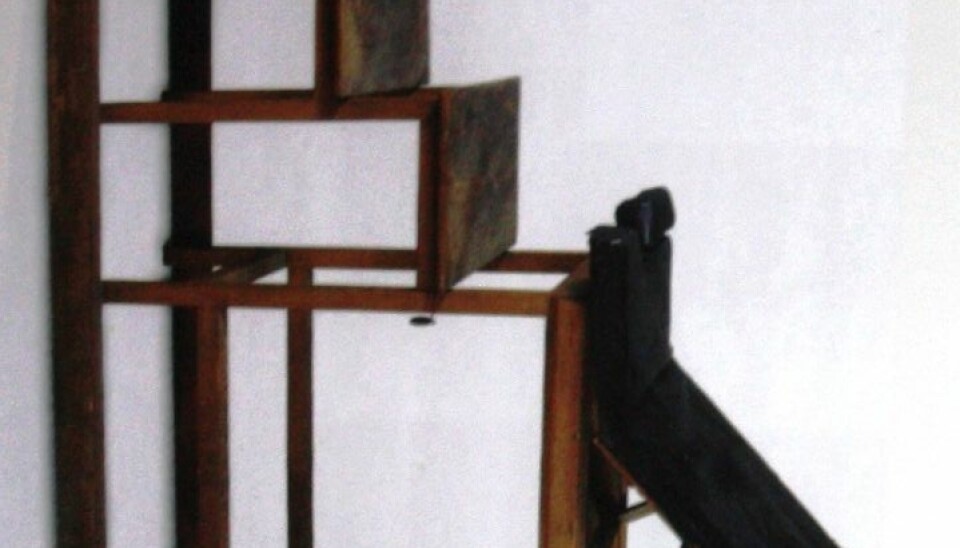

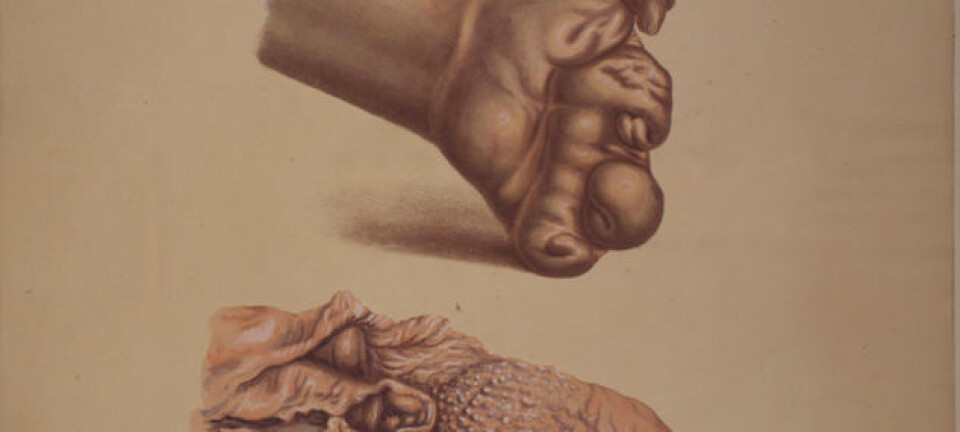

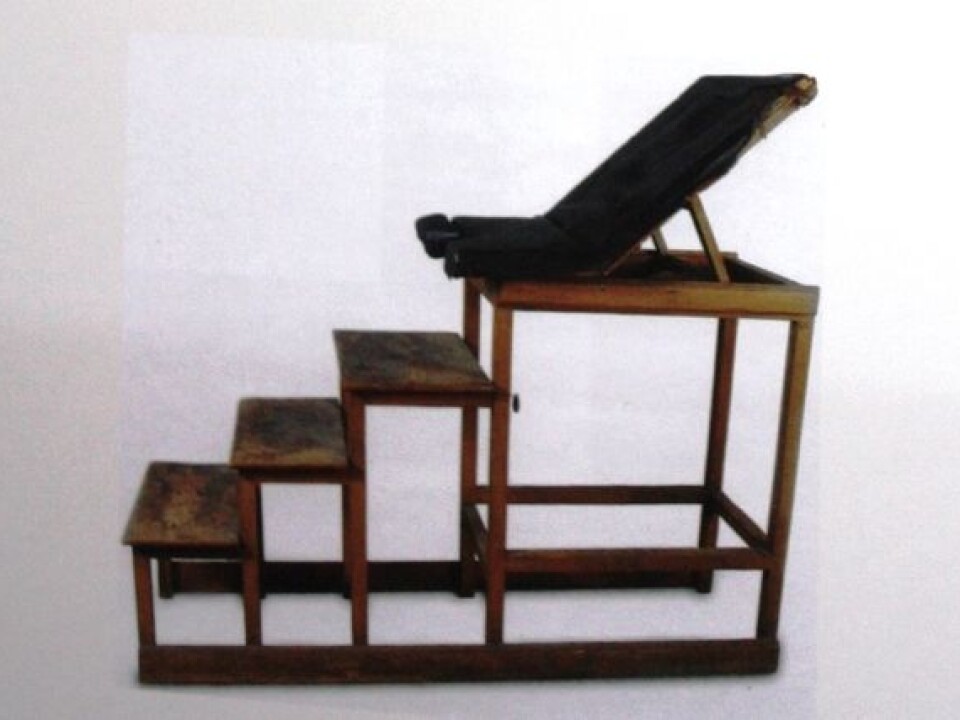

She points to the large painting comprising the central work in the exhibition – Albertine to see the Police Surgeon, which the Norwegian artist, journalist and author first exhibited on 11 March 1887.

It depicts a scene from Krohg’s book Albertine, published in 1886. The young woman Albertine is about to partake in the so-called visitation – which included a gynaecological examination – for the first time.

Albertine is apprehensive about the examination, as we can understand the young women we see in the police files when they were questioned and submitted to such a probe for the first time. This was the Victorian era and it’s easy to imagine the trepidation of the young women photographed in the police album felt prior to their first check-ups.

As Christian Krohg perceived them, they still hadn’t lost their sense of shame.

Provoked by hypocrisy

A law against prostitution was passed in Norway in 1842, yet the authorities decided that men needed to have an outlet for their libidos before they wed.

So a system was established – a controlled continuance of prostitution, for society’s, and particularly the customers’, convenience.

The women had to attend such visitations as often as twice a week.

Another rule kept them off certain streets and parts of the city at designated times in the afternoon. For what if a gentleman strolling arm in arm with his wife were to run into a woman of ill repute whose services he’d recently enjoyed?

The whores faced prosecution and incarceration if they failed to abide these rules.

These were the conditions that provoked Krogh and other radicals of the day. A debate about prostitution raged in the newspapers and Krogh did his bit to attack the hypocrisy through his novel and his painting.

His novel about Albertine was banned and led to litigation. Unabashed, he upped the ante by painting his protagonist Albertine outside the inspection room, and the scandalous picture was exhibited in Kristiania.

“You can imagine that many of the visitors at the exhibition were men who had visited the brothels, and perhaps their wives accompanied them to the art show. It must have been embarrassing – perhaps many steered clear of it altogether,” says Hansen.

Job hunters

Who were these girls and women who established themselves in the city’s brothels?

The official records from what you could call the Kristiania Vice Squad reveal the women were not just poor lasses from greater Oslo – they were women from all over the country, north to south, who were desperate for work.

Many of them were newcomers to the city. The police protocols provide the data; their date and place of birth are listed.

The women in the album could be from the outskirts of the capital, or all the way from Grimstad and Kristiansand in the south to Norway’s northernmost county, Finnmark. But some were also locals born in Kristiania.

“Here’s a local girl: ‘Kristiane Kristiansen, age 16, comes from the city. Initial visitation: 26.3.1884’,” Hansen reads from the police protocol.

The day this information was written down was her first visit to the police doctor, just like Albertine in Krohg’s painting.

Not just the proletariat

Why women came so far and became prostitutes can be partly explained by contemporary Norwegian demographics and social developments.

“The capital city experienced its biggest population boom ever,” says Hansen.

In 1845, just a little more than 100,000 people lived in Oslo and its surrounding Akershus County. In 1900 the figure had risen to nearly 350,000, according to Statistics Norway.

“People poured in looking for work but not everyone could find decent jobs,” explains Lerberg. “The alternative might be to toil long hours in the toxic airs of some factory.”

Nor did all the prostitutes come from dire circumstances. Nicolai Rygg, who worked at Statistics Norway from the late 1800s, started a survey of prostitution in Kristiania just a few years later, in 1907, showing that some were not working class girls.

Out of the 304 women in his study, about half came from proletarian homes, while one was the daughter of a factory owner. Seven had fathers who were sea captains, eleven came from families in commercial trades and 41 were farm girls.

Photo picked up by husband

“Do you see these empty spots?” says Hansen, pointing to yellowed squares between some of the photographs.

On one we read: “Married 7.4.94. Remitted to her husband, Georg Dahl.”

If we were allowed to remove the album from its display case at the National Gallery and leaf through it, we’d come across more of these empty spots where official photos of prostitutes have been removed. The women could be stricken from the archives once they quit selling sex.

In other empty slots we read: “Emigrated to America – photograph picked up by mother” or tersely “Died”.

If one of the ladies quit the brothel and found a husband, Hansen and Lerberg agree he wouldn’t be a wealthy saviour from the posh side of town.

You mean there were no Pretty Woman stories?

“Very little that would remind us of Pretty Woman here,” says Lerberg, looking at the album full of female faces with eyes fixed on unknown photographers.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling