Here's what researchers encountered in Norway's deepest hole

At a depth of 3,500 metres, the remotely operated submarine discovered something very special.

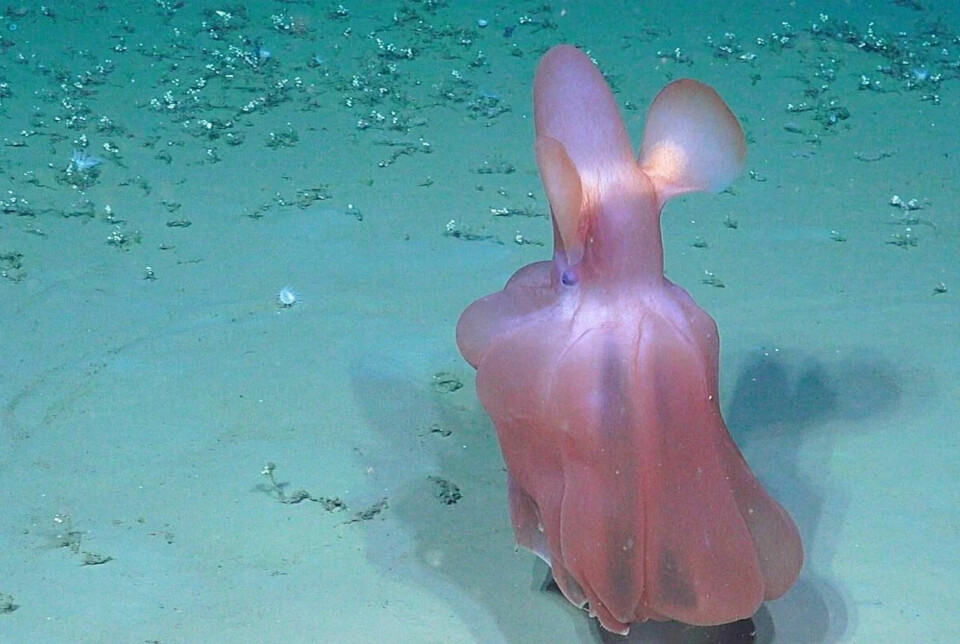

Like a dancer in a ballerina skirt, it floated over.

With the icebreaker Kronprins Haakon, one of the world's most advanced research vessels, researchers are now on an expedition to the deep sea northwest of Svalbard.

It was during the night between Saturday and Sunday that they were going to make the first dive into Norway's deepest hole.

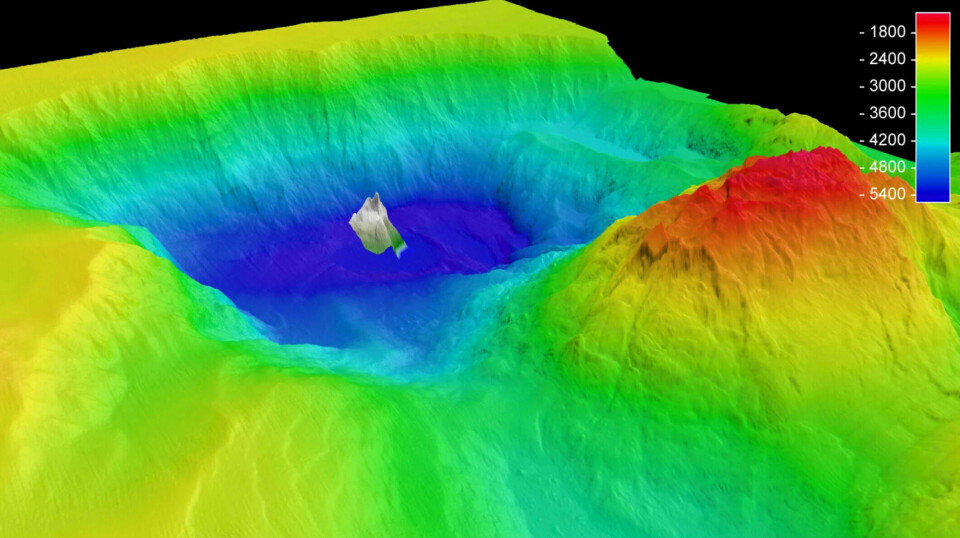

The Molloy Deep plunges a staggering 5,569 metres below sea level. That’s more than twice as deep as Galdhøpiggen, the highest mountain in Norway, rises above sea level.

Revealing the Earth's mantle

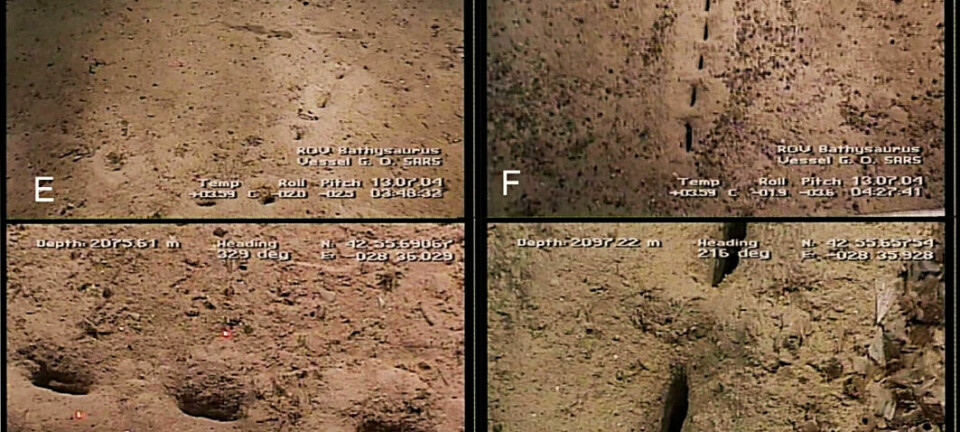

The Molloy Deep in fact goes so deep that much of the surface down there reveals the Earth's mantle, which is hidden beneath the Earth's crust.

This is what the researchers want to examine more closely.

Equipped with 15 laboratories and some of the most advanced equipment ever delivered to a research vessel, the Kronprins Haakon is being used this summer for an expedition called GoNorth.

Remotely operated submarine

On board the Kronprins Haakon, the researchers have brought along the remotely operated submarine Ægir 6000 from the University of Bergen. It can dive to a depth of 6,000 metres.

The octopus that the submarine encountered on its way down into the depths belongs to the genus Grimpoteuthis. These octopuses are popularly known as Dumbo octopuses.

No other octopus can dive as deep in the ocean as the Dumbo octopus.

This octopus has a kind of fin on the side of its body that makes it resemble Dumbo, the flying cartoon elephant with big ears.

Grimpoteuthis lives at depths of 1,000 metres and below. It may even go as deep as 7,000 metres.

The Molloy Deep

The Molloy Deep may have formed 30 million years ago.

It is located exactly where the mountain range of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge takes a sharp turn. It is known that such bends in large underwater mountain ranges can create deep ocean depths.

The GoNorth expedition with the Kronprins Haakon this summer is thus heading to the Arctic depths between Svalbard and the North Pole. The main objective is to determine the composition of the Earth's crust in this area. The researchers are focusing on the part of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge called the Gakkel Ridge.

The Gakkel Ridge stretches 1,800 kilometres from the northern end of the Fram Strait between Svalbard and Greenland, extending further towards Siberia.

Along the ridge, two of the Earth's major tectonic plates are moving away from each other. But nowhere else on Earth does this tectonic movement occur as slowly as right here. The researchers find that interesting.

Because the surface of the Gakkel Ridge is covered with ice for most of the year, researchers have known very little about it until now.

The plan is for the Kronprins Haakon to collaborate with the German research ship Polarstern in mapping the Gakkel ridge this summer.

The two ships will sail side by side at a steady pace, while both send seismic waves down towards the seabed. However, this is easier said than done when the sea surface is covered with ice.

Also involves politics

This Norwegian research in the Arctic also has political implications. Minister of Fisheries Bjørnar Skjæran (Labour Party) openly acknowledges this in an interview with the GoNorth expedition's own website.

Even though the Gakkel Ridge lies beyond Norway's maritime border north of Svalbard, this research is also a way for Norway to demonstrate its presence in the Arctic Ocean. It helps to secure Norway's interests in the Arctic.

At the same time, this research involves Norwegian researchers collaborating with colleagues from Germany, the USA, and other Nordic countries.

Norway now has one of the world's most modern research vessels. Kronprins Haakon is constructed with steel plates that are up to 40 millimetres thick and can maintain a steady speed of 3.5 knots through a metre-thick solid ice. If the ice becomes even thicker, the ship can reverse and gain momentum, allowing it to climb onto the ice and use its own weight to break it down. (Video: Marius Bratrein / the Norwegian Polar Institute)

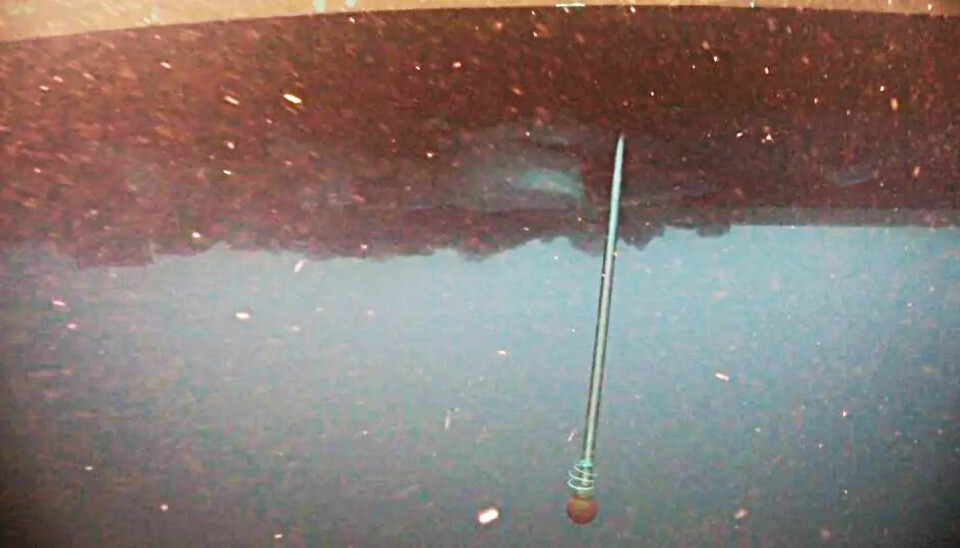

Damaged instrument

Research into the Arctic sea ice is challenging.

Ice floes of several tens of tonnes drifted by while the Kronprins Haakon was positioned over the Molloy Deep last weekend.

Just a few hours after the encounter with the Grimpoteuthis octopus in the depths, unfortunately, an instrument that extends into the sea beneath the research vessel was damaged by ice.

A large chunk of ice hit the pipe on Sunday. As a result, the instrument can no longer be retracted into the hull.

Now, the Kronprins Haakon is slowly making its way back to the port in Tromsø.

According to the plan, the instrument will be cut off and replaced with a new one as quickly as possible, so that the expedition to the deep sea northwest of Svalbard can continue while it is still the Arctic summer.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References:

GoNorth expedition's website and daily reports from the 2023 expedition.

Wikipedia page on Grimpoteuthis octopus