Here’s what it looks like 4000 meters below the Arctic ice

Far below the Arctic ice lies a special area with volcanic activity. What lives down there? Scientists have gone on a journey to find out.

Hydrothermal vents were first discovered in 1979. They look like pipes sticking out of the seabed and emit warm "smoke", which is actually hot fluid loaded with minerals.

In the Atlantic and Pacific, many of these vents, also called chimneys, are surrounded by unique ecosystems with clams, blind shrimp, beard worms and extremophile bacteria.

Life there does not get its energy from the sun, but from the interior of the earth.

Microorganisms use reduced compounds from the vents as an energy source to make organic matter, just as plants and algae use photons from the sun. Larger animals live in symbiosis with these microbes.

However, no one has previously looked at the fauna in this type of area in the Arctic.

What lives in these cold, deep waters, 4,000 metres below the ice?

“We wanted to see if this ecosystem had developed in isolation — whether it is very different from other places with hydrothermal vents, or whether the fields are interconnected,” says Eva Ramirez-Llodra.

She is a marine biologist at the Norwegian Institute of Water Research (NIVA).

Along with an international team of researchers, she has been on a research cruise to 82 degrees N. The hope was to find Aurora, a volcanic field on the sea floor with hydrothermal vents known as black smokers.

Previous expedition found vent

Researchers were allowed to use the RV Kronprins Haakon, Norway’s new icebreaker, and departed from Longyearbyen, on the arctic archipelago of Svalbard, on September 19.

Eleven international institutions were represented aboard the boat. A writer from National Geographic and a photographer from James Cameron's Avatar Alliance Foundation also participated in the month-long trip into icy waters.

Chemical signatures in the water have previously revealed that there are hydrothermal vents in this northern region, more specifically on the subsea mountain ridge called the Gakkel Ridge.

German scientists from the Alfred Wegener Institute doggedly searched for the vents in 2014. After five weeks of exploration, they hit the jackpot on the last day of the expedition.

“They drifted over a hydrothermal chimney and got under a minute of video of it. That allowed them to know where it was,” Ramirez-Llodra says.

Now a team has re-visited the area, and the plan was to take both videos and samples of the organisms living in the depths. The expedition was led by UiT - The Arctic University of Norway and NIVA. Eva Ramirez-Llodra was the project manager.

Cheers and hugs

"It was hard to plan the days, because you work at the mercy of the ice," says Ramirez-Llodra.

Arctic sea ice is not quiet. It breaks up, freezes, and varies in thickness. That made it difficult to get to the right place. The researchers towed a camera after the boat to film the seabed.

On October 3, they finally got a good position over what they believed was the field. Everyone's eyes were fixed on the screens in the control room and the tension was high.

“When the chimney first appeared, we exploded in cheers and hugs,” the researchers wrote on a blog about the cruise.

It was a huge hydrothermal vent, a black smoker, and later the researchers found two others.

“We could see that we were approaching the vents, because the sediments became coarser, and there were more stones and colours on the sea floor,” Ramirez-Llodra says.

One encounter was a little close. The researchers pulled the camera up over a mound, and suddenly they saw black smoke billowing out of a gaping, underwater crater.

“It’s not actually smoke, but very hot liquid at about 350 degrees C. The camera ran right into it. It went so fast that we couldn’t stop it. Everything went black and we were scared that we had burned everything up,” she says. “Fortunately, we got the picture back after a few minutes. We could continue. This was our first close encounter with a black smoker.”

Golden fields and glass sponges

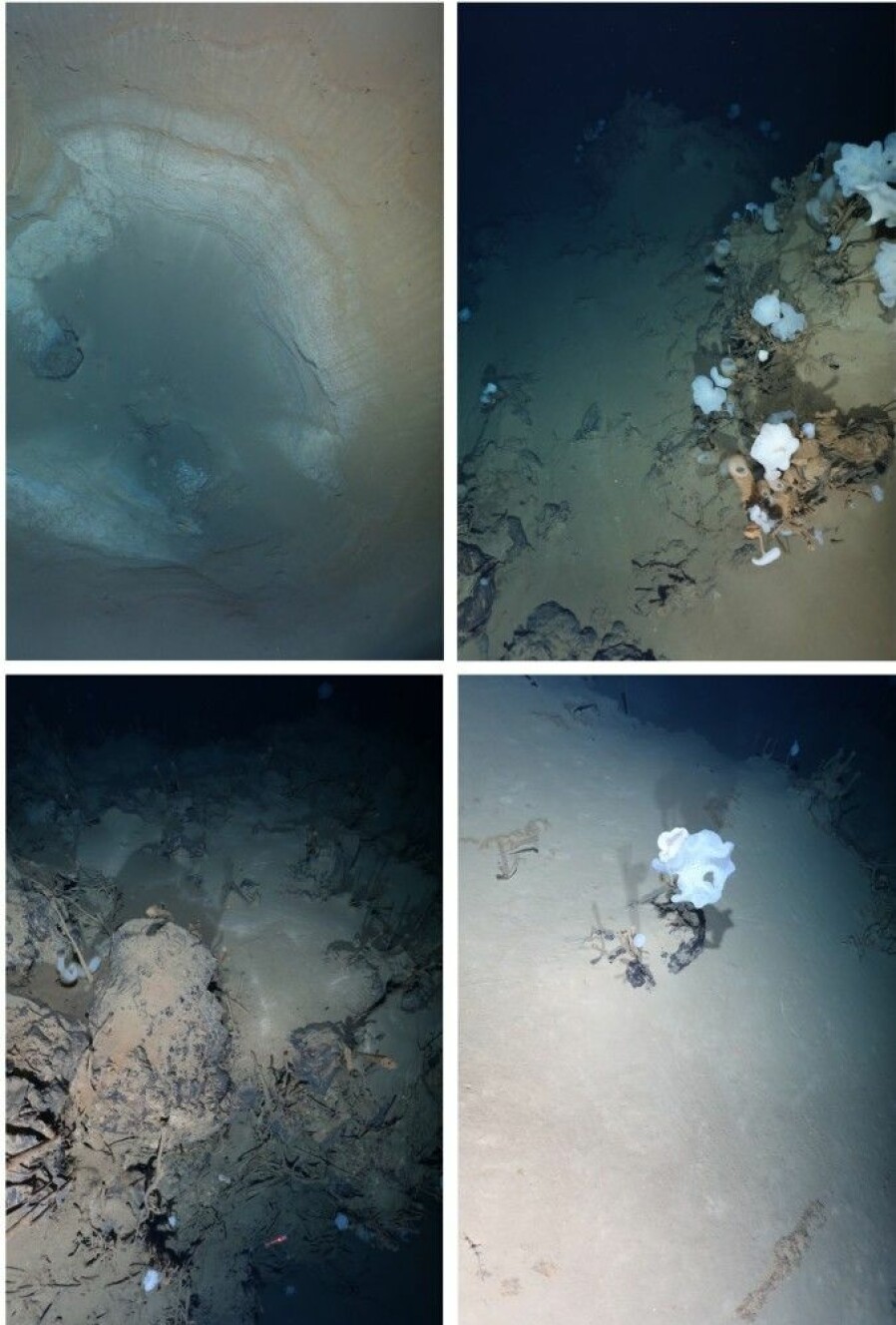

Scientists saw fields that shone like gold on the otherwise colourless bottom around the chimneys.

The material the researchers saw wasn’t gold but sulphite that is deposited by the black "smoke", Ramirez-Llodra says, although there are also traces of gold and silver in the fluid that gushes from the vent. Around the vents were clusters of white organisms that glistened as they reflected the light from the camera.

The area around the Aurora field was covered by a thick layer of fine-grained sediments. Where the ground was solid enough for something to stick, there were white, spooky sponges. There were shrimp frolicking in the depths, and sea cucumbers and anemones. The occasional fish also swam around.

But the bulk of the organisms in the depths were glass sponges. They are relatively rare, can grow up to a metre wide, and some of them can live for several centuries, according to an article about the trip written by National Geographic. The sponges are largely made up of silica, and only a little of their mass is organic matter. They can be said to barely be alive.

Very different from fields further south

The researchers did not find the diversity of life that has been discovered around hydrothermal vents in other ocean areas.

“There wasn't much life down there,” says Ramirez-Llodra. “But we’re not exactly sure why yet.”

Hydrothermal vents in the Atlantic and Pacific contain colourful communities of beard worms, clams and crabs that have adapted to the special environment around the vents.

“Most of these have a symbiotic relationship with bacteria and microorganisms that live by chemosynthesis. The bacteria can be inside their bodies or in special organs,” says Ramirez-Llodra.

“Some organisms don’t even have a mouth or digestive system, but only live from what the microbes inside their body produce.”

Ramirez-Llodra says the researchers don’t know yet if there is a similar relationship between organisms around the vents in the Aurora field.

“We have to analyse the videos more carefully first,” she said.

The researchers got plenty of samples from animals that lived on the undersea ridge. But due to technical problems, they were unable to take samples right next to the vents. A new expedition will be needed to collect animals and microbes that live close to the vents.

May be similar to conditions on ice moons

Microbiologist Dimitri Kalenitchenko collaborated with Kevin Peter Hand, astrobiologist from JPL, NASA, on a slightly different project up on the surface of the ice.

NASA plans to send a spacecraft to look for traces of life on Jupiter's ice moon Europa. Both Europa and one of Saturn's moons, Enceladus, are covered by a thick layer of ice. But they probably have seawater beneath the surface as well as hydrothermal activity on the seabed.

In other words, they may look a little like the area the scientists visited in the Arctic. How much can a spacecraft find out about potential life on the moons, far below the ice?

The researchers took samples of the ice over the Aurora field. The goal is to see if they can find evidence of the vents that are 4000 metres below.

“We are trying to see how much the ice can capture signatures from the water below,” says Dimitri Kalenitchenko, a researcher at UiT - The Arctic University of Norway and the CAGE research project.

He will also look for extremophile microbes in the ice samples from the expedition. These are organisms that are typical of hydrothermal vents and that thrive in the heat down there. The idea is that they may have somehow been driven off the area and come right up to the surface. There they may have been trapped in the ice and lie in some kind of hibernation.

"The big question is whether the microbes are present in the ice or whether it is hopeless to find them," Kalenitchenko said.

He expects to have the answer in the middle of next year.

Will go back

Additional studies of the videos and samples the researchers took will reveal more about the previously unknown environment on the Gakkel Ridge.

Ramirez-Llodra says they will embark on a new expedition later, to take samples even closer to the vents.

Both Ramirez-Llodra and Kalenitchenko agree that the expedition was rewarding, perhaps especially because of the good atmosphere on board.

“Although we had some problems and did not get to take samples from right around the hydrothermal vents, everyone was very enthusiastic to continue the work,” Ramirez-Llodra says.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no