A lost Viking town discovered in the 1950s is stored away in this basement

Not until recently have researchers really started studying a thousand-year-old Norwegian town we know surprisingly little about.

When a piece of land near Borgund church on the West coast of Norway was to be cleared in 1953, a lot of debris was uncovered.

Luckily, some recognised the ‘debris’ for what it really was: objects from the Norwegian Middle Ages.

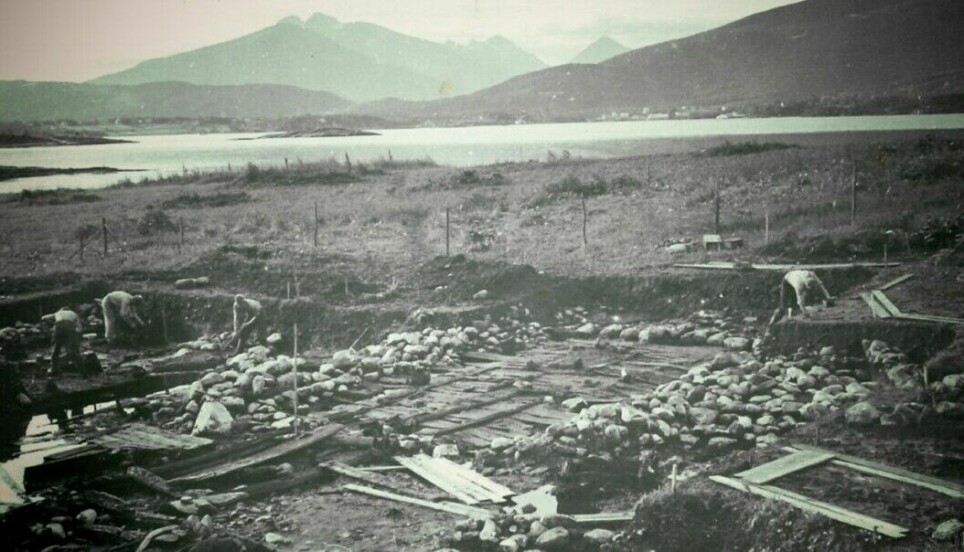

The following summer, an excavation was undertaken. Archaeologists retrieved many, many items from the ground. Most of them were taken into storage.

Then not much else happened.

Now, nearly 70 years later, researchers have started the exhaustive work of analysing the 45,000 items in storage in order to gain insight into a thousand-year-old Norwegian town we know surprisingly little about.

Built in the Viking Age

“Borgund was probably built sometime during the Viking Age,” Professor Gitte Hansen says.

In the few written sources we have about Borgund in the Middle Ages, it is referred to as one of the ‘small towns’ (smaa kapstader).

sciencenorway.no meets the archaeologist at the University Museum of Bergen. She takes us down to the basement.

Behind a simple door with an ‘Alarm’ sign on it are tens of thousands of objects from the forgotten town, excavated more than half a century ago.

What was Borgund?

The story of Borgund begins sometime in the 900s or 1000s.

Fast forward a few hundred years and this was the largest town along the coast of Norway between Trondheim and Bergen.

Activity in Borgund may have been at its most extensive in the 13th century.

In 1349, the Black Death comes to Norway. Then the climate gets colder.

Towards the end of the 14th century, the town of Borgund slowly disappeared from history.

In the end, it disappeared completely and was forgotten.

An international team

“The 45,000 objects from the 5,300 square meter excavation area in Borgund have just been lying here,” the Danish archaeologist Gitte Hansen tells us. “Hardly any researchers have looked at this material since the 1970s.”

It was Hansen who took the initiative to the research project where she and several colleagues are now thoroughly examining the large amount of material.

With a few million NOK from the Research Council of Norway and contributions from several other Norwegian research institutions, in addition to help from researchers in Germany, Finland, Iceland, and the USA, a team has been put together comprising everything from textile researchers to experts in the Old Norse language.

It's a very competent team, Hansen assures.

Together they have started to tackle the Borgund mystery.

Lots of textiles

Hansen admits that examining such extensive archaeological material is a big job.

Much of what was found in Borgund is textiles from the Viking Age and the Norwegian Middle Ages. They can tell us new things about the clothes people wore in Norway a thousand years ago.

But how well has this material held up?

The textiles were dug up as long as 60-70 years ago. Although the items were put into storage, this was mostly done without conservation work.

"I'd rather talk about something else," the project manager sighs.

“Though really we are just lucky that the archaeologists collected this great source material at all,” she says.

Pioneering work at the time

The excavations in Borgund in 1954 were led by Asbjørn Herteig. He was one of the pioneers of modern medieval archaeology.

Herteig was one of the first archaeologists in Europe to collect the remains of ordinary medieval people.

“Before Herteig, archaeological interests lay mostly in churches, monasteries, and castles,” Hansen says.

Herteig on the other hand, collected trivial things from the Middle Ages.

"Items such as shoe soles, pieces of cloth, slag (the by-product of smelting ores and used metals), and potsherds are archaeological sources that can tell us about the everyday life of ordinary people," says Hansen.

"And can you believe how lucky we are to still have these items - in a condition that allows us to do research on them!", she says.

All the way back to the 10th century

Gitte Hansen hopes that the Borgund findings will give us many answers. Perhaps discoveries that were not possible for scientists to make in the 1950s and 1960s.

“Establishing exactly when Borgund existed will be an important job,” she says.

We are talking about a dense settlement of houses and at least three marble churches that covered a fairly large area by the Borgundfjord some distance within Ålesund on the West coast of Norway. The fjord is known for ‘Borgundfjordfisket’, a rich cod fishery that often takes place in late winter in February and March.

Analyses of ceramics, textiles, remnants of iron, and grindstones from Borgund have already begun to yield results.

“We now see that Borgund must have existed already at the end of the 10th century,” the archaeologist says.

According to Hansen, there seems to have been a lot of activity in Borgund until around 1350. There is also some activity after this.

“But it is too early to say for sure how long the town existed,” she says.

The contact with Europe

In the remains of Borgund down in the basement under the museum in Bergen, researchers are now discovering ceramics from almost all of Europe.

“We see a lot of English, German and French tableware,” Hansen says.

People who lived in Borgund may have been in Lübeck, Paris, and London. From here they may have brought back art, music, and perhaps inspiration for costumes.

The town of Borgund was probably at its richest in the 13th century.

“Pots and tableware made of ceramic and soapstone from Borgund are such exciting finds that we have a research fellow in the process of specialising only in this,” Hansen says. “We hope to learn something about eating habits and dining etiquette here on the outskirts of Europe by looking at how people made and served food and drink.”

- RELATED: What did the Vikings really eat?

Life in Borgund

What was it really like to live in a small town on the outskirts of Europe in the Middle Ages?

How was their everyday life? What did they eat? Did they wear the same clothes that people elsewhere in Europe did at that time?

It already seems quite obvious to Gitte Hansen that the people in Borgund were not natives.

“There are many indications that people here had direct or indirect contact with people across large parts of Europe,” she says.

It has previously been thought that fishing was important to the inhabitants of Borgund. Did they partake in the extensive stockfish trade between Northern Norway and Europe? Did the inhabitants of Borgund perhaps deliver a lot of fish to the German Hanseatic League in Bergen?

Fish was important

“There is much to suggest that fish was important in Borgund,” confirms the project manager.

In a collaboration with the NTNU University Museum in Trondheim, a research fellow there is examining the many fish bones that have been found in Borgund. Many are leftovers from whole fish. The researchers interpret this as meaning that the inhabitants themselves ate a lot of fish.

“We have also found a lot of fishing gear. This suggests that people in Borgund themselves may have fished a lot. A rich cod fishery in the Borgundfjord may have been very important for them,” Hansen says.

The remains from ironwork tells us that the forgotten town in Western Norway had several legs to stand on.

Maybe this was a town where blacksmiths had a particularly important role?

And why in the world did Asbjørn Herteig and his colleagues find lots of shoemakers’ waste materials? As many as 340 shoe remains can tell us about both shoe fashion and what kind of leather people preferred for their shoes in the Viking Age.

A total of 250 textile pieces

Even though the textiles from Borgund have not been stored as well as the researchers today would have liked, there is still a lot to investigate.

At first, scientists thought they had 150 pieces of textile from the excavation which was undertaken more than half a century ago.

Now they see that there are in fact 250 pieces.

“A Borgund garment from the Viking Age can be made up of as many as eight different textiles,” says Hansen.

A royal decree from 1384

From the historians' written sources, we know surprisingly little about Borgund.

That is why archaeologists and other researchers are so important in this particular project.

But one important historical source does exist.

It is a royal decree from 1384 which obliges the farmers of Sunnmøre to buy their goods in the market town of Borgund (kaupstaden Borgund).

“This is how we know that Borgund was considered a town at the time,” Hansen says. “This order can also be interpreted as Borgund struggling to keep going as a trading place in the years after the Black Death in the middle of the 14th century.”

And then the city was forgotten.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no