Why was there a such huge amount of down in the Oseberg Viking ship?

The down found in the ship could have filled at least 31 duvets. An archaeology professor has a theory about what it might have been used for.

“I think it looks like they've taken shovels and just scooped it into dresser drawers,” Marianne Vedeler tells sciencenorway.no.

She is a professor of archaeology at the Museum of Cultural History.

“There were a lot of clay flakes mixed in with the down,” she says.

Vedeler is referring to the enormous amount of down found during the excavation of the Oseberg Ship in 1904 – the most magnificent Viking grave that may ever be found, as archaeologist Hanne Lovise Aanestad described it.

The down was set aside and then rediscovered in 2009, in the original drawers and boxes where it had been placed over a hundred years earlier.

Vedeler helped unpack and examine the large quantities of down, along with the clay mixed in between.

The down floated in puddles of mud

When she weighed the down that had been brought to the museum, it ended up weighing over 31 kilos. And that was just the down that the archaeologists took with them.

For comparison, a high-quality down duvet contains around one kilo of down.

“There was probably a lot left behind,” she tells sciencenorway.no.

During the excavation, there were periods of extremely bad weather and heavy rain. Thick layers of down floated in puddles of mud inside the burial chamber, Vedeler described in an article about the textile finds from the Oseberg Ship.

It turns out this is far from the only Viking Age grave containing down.

But why was all this down buried in these graves?

The burial chamber of two women – filled with treasures

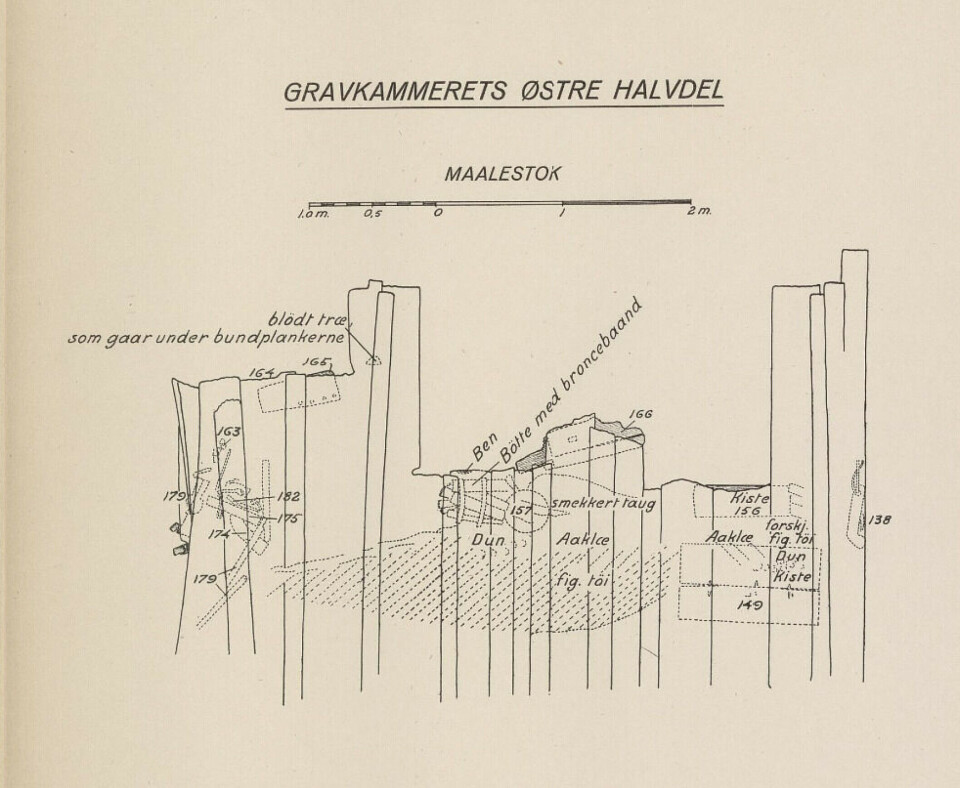

The burial chamber was located on the deck of the Oseberg Ship, and contained the remains of two unknown women, for whom the entire grave was presumably built.

They were buried with an extensive selection of treasures. The intricately carved animal heads and the Oseberg wagon are just a few examples of these highly elaborate artefacts.

“These were high-status items, both in their nature and craftmanship,” says Vedeler.

Countless hours of labour must have gone into creating many of these items. One example is the remarkably well-preserved 'Buddha bucket' – a Celtic yew bucket likely originating from the UK.

Collecting all that down must have been a significant undertaking as well.

Vedeler finds it unlikely that the large quantities of down were intended for duvets. She suggests it may be the remnants of a giant mattress.

Was it a giant mattress?

Vedeler also argues that the well-known carved animal heads found in the grave may be connected to this possible bed.

“We actually know very little about it. What we can say is that they were found in each corner of this huge accumulation of down,” she says.

The animal heads were found in the burial chamber, tied together with rope, Vedeler wrote in this article.

It is therefore possible that the unknown women in the grave were laid on a huge mattress filled with down. Remnants of what could be a plant-based fabric were also found, which could have been the mattress cover, according to Vedeler.

Much of this is speculation.

Although a great deal of the Oseberg Ship and the objects in the grave were so well-preserved that even the down survived over a thousand years in the soil, the grave had been heavily disturbed.

Grave robbers opened the burial chamber from the top around 100 years after it was sealed and removed the women's remains.

An incredibly difficult puzzle

‘The grave robbers removed the skeletons from the chamber and dragged them up through the opening they had dug. Why they did this is not something we need to examine here at this moment.’

This is how the Oseberg archaeologists described what the grave looked like in the first volume of The Oseberg Find from 1917. They also describe large amounts of down found under a bier in the burial chamber, though it was unclear whether this bier was part of the original grave or a result of the intrusion.

Figuring out how the burial chamber looked when it was first sealed is challenging, according to Vedeler.

“This is an incredibly difficult puzzle that we aren’t even close to solving,” she says.

At some point, this mattress – if it was indeed a mattress – developed a tear. It might have happened during the grave robbery or when the chamber itself collapsed, says Vedeler.

“When a mattress tears, you can imagine what would happen next. Down flies everywhere, mixing with everything else in the chamber,” she says.

Tapestries on top of the mattress?

Some of the items that might have been mixed with the down were tapestries from the Oseberg grave. Down has stuck to the back of several of these intricate and highly detailed tapestries. Some of the motifs depict battles and processions with horses and carriages, which you can read more about on sciencenorway.no.

Some of the tapestries were folded and placed inside or near a chest in the chamber. Other tapestries may have lain on top of the mattress, Vedeler suggests.

“The most famous tapestries were placed on top, on display,” she says.

Researchers still do not know what type of down was found in the Oseberg grave. Vedeler cites an analysis from the late 2000s, which concluded that much of the down could have come from seabirds such as frigatebirds, cormorants, ibises, and oystercatchers.

“But precisely what kind of seabird, we don't know,” she says.

There are other graves from the Viking Age where down has been found, and researchers know which bird species it came from.

Pillows for warriors

“Down is soft and quite insulating. It retains its structure even when compressed,” Jørgen Rosvold tells sciencenorway.no.

Rosvold is the research director at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA) and has expertise in identifying bird species from archaeological finds.

“Down is a material that's rarely preserved in soil. Finding feathers in an archaeological context is rare,” he says.

Rosvold helped examine a feather find from a grave in Valsgärde in Sweden, dated to the 600s CE. This was a little earlier than the Viking Age and the Oseberg grave. The find was described in a research article from 2021.

In this study, researchers argued that warriors in the graves lay on feather-stuffed mattresses. Rosvold helped determine that the feathers came from many different bird species and that there was little evidence that they had been traded over long distances.

“There's quite a bit of variation in the feathers used in different places in Norway and Sweden,” says Rosvold.

“This suggests that feathers were generally an important material. They may have simply saved whatever feathers they had available,” he says.

Most of the feathers in Valsgärde came from various geese and ducks, including eider ducks. The researchers also found more unusual pillow feathers – from owls.

How can they see differences in ancient down?

“We examine the feathers under a microscope, looking at all the fine, small structures and the distribution of pigment on a millimetre and micrometre scale. This allows us to distinguish different bird groups from one another, sometimes even down to the species,” says Rosvold.

In addition to the Oseberg grave, Rosvold highlights the Grønhaug grave on Karmøy, where down was also found. The discovery is described on the University of Stavanger's website (link in Norwegian).

Another well-known example is detailed in this 2016 research article, which describes the identification of feathers found in the Øksnes grave in Vesterålen.

This ship burial was opened in 1934 and dates back to the 10th century. The remains in the grave were wrapped in an animal hide. Inside this hide, archaeologists also found a pillow, where both feathers and fabric had been preserved.

Researchers were able to identify the sources of the down: eider ducks, cormorants, and unspecified gulls.

Rosvold has also worked with down from the Oseberg grave, but these results have not been published yet.

You can read more about the identification of feathers that Vikings put in their pillows in this article from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

Transport to the afterlife?

Regardless of what kind of bird feathers were placed in the grave with the dead, it remains uncertain as to why they were there. In the same way that the Oseberg Ship was crushed by large stones before being enclosed in the burial mound, the meaning behind these items and any associated rituals has been lost over centuries.

“We can speculate almost endlessly about what this mattress represents. Could it be a form of transport to the afterlife? There are several interpretations of the burial chamber. Could it represent a noble bedchamber?” asks Marianne Vedeler.

Or perhaps it’s as simple as these items being there for practical purposes, Vedeler suggests. Maybe the feathers were included because they would be useful in the afterlife.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.