Why are there nine men hanging from a tree on this Viking tapestry from the Oseberg grave?

Were they sacrificed?

And what other secrets do the woven images reveal?

Nine men who may have been sacrificed – modern technology aims to uncover more from the Oseberg tapestries

Over 100 tapestry fragments were found in the Viking burial mound.

Researchers are now using modern technology to restore the motifs.

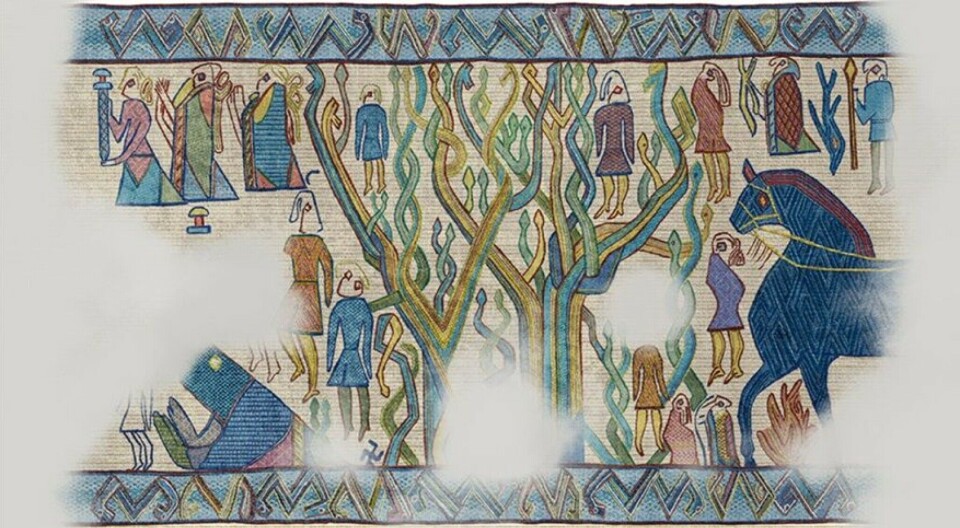

A tree stretches towards the sky, its branches intertwined, and figures hang from them.

Were these men sacrificed or executed?

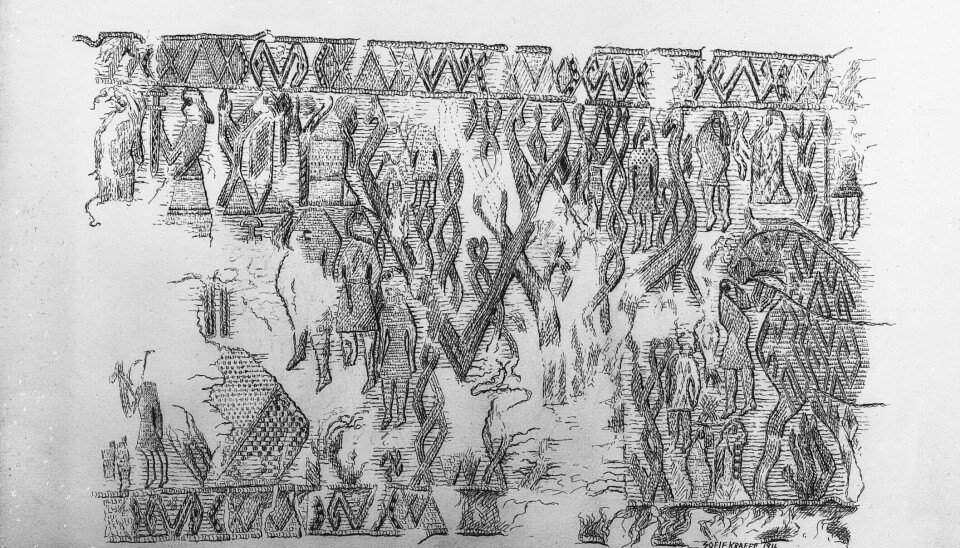

Though the tapestry is poorly preserved, it tells a gripping story. Folded and placed in the Oseberg burial mound when it was sealed in 834, it remained hidden underground, along with other woven textiles, until the grave was opened in 1904.

Could it be Yggdrasil?

“We see a tree with many branches and roots,” says Marianne Vedeler, describing the fragment.

She is a professor at the Museum of Cultural History and has spent countless hours examining images of the delicate fragments under a microscope. She is also the author of The Oseberg Tapestries.

Vedeler retrieved the Viking textile from a shelf in the museum’s storage, housed in a rather unassuming office building in eastern Oslo, where many of Norway’s most significant cultural artefacts are stored.

The fragment depicting the tree is small, only 16 centimetres wide. It is made of wool and a plant-based material that has almost entirely disappeared. The colours have faded, and there are holes in the textile. But the tree is still visible.

What did the original tapestry look like, and what story was it meant to convey? An artist, inspired by the ancient weaving, has created the colourful illustration below, though it represents a modern interpretation of the image.

“There might be nine men hanging from the branches here,” says Vedeler. “That immediately brings to mind Yggdrasil.”

Yggdrasil, the world tree in Norse mythology, is linked to well-known tales of Odin, who is said to have sacrificed himself by hanging from its branches. It is also believed that human sacrifices may have been made during the worship of Odin.

This is one interpretation of the grim motif revealed in the fragments.

At least three tapestry works

“Some graves contain small fragments of tapestries, but none contain full scenes like this,” says Vedeler.

It is unclear how many complete tapestries were placed in the Oseberg grave. Marianne Vedeler estimates that there are at least three distinct tapestry works, though no one can say for sure.

In her book, she suggests that the tapestry featuring the nine men is a standalone piece, noting that the image focuses on the tree and that the fragment was folded and placed apart from the others.

There are several mysterious elements in the scene, including a large, prominent horse and some kind of mythical creature raising its arms.

Swastikas in the images

There are also many small swastikas scattered across the tapestry fragments from the Oseberg burial mound.

“The swastika is an ancient symbol that’s been used in the Nordic region since the early Iron Age,” says Vedeler.

It’s even older than that, with examples dating back thousands of years BCE.

“It likely held different meanings over time, and we don't know what significance the Vikings attached to it,” she says.

Much smaller than the Bayeux Tapestry

The Oseberg tapestries are tiny in comparison to the famous 70-metre-long Bayeux Tapestry.

They are so small that you have to get up close to see the story they depict.

“Maybe it's about control. These tapestries tell stories, and from medieval sources, we know that kings who owned valuable textiles and tapestries also controlled the narratives,” says Vedeler.

“There may have also been a link between the tapestries and what a skald recited, with the skald incorporating the tapestry into their performance,” she says.

According to Vedeler, such tapestries may have been hung on the wall during festive occasions, only to be packed away once the performance ended.

Possibly the world's most famous Viking grave

Over 100 fragments have been uncovered from the Oseberg burial mound.

The Oseberg burial is considered one of the most famous and wealthiest Viking graves in the world. While the Oseberg Ship is its most well-known artefact, many other exquisite and practical objects were buried alongside it.

The grave contained the remains of two women, though their identities remain a mystery. Yet, the significance of the burial is undeniable. The grave was looted and disturbed about a hundred years after it was sealed, so no one knows exactly what it looked like when it was originally constructed.

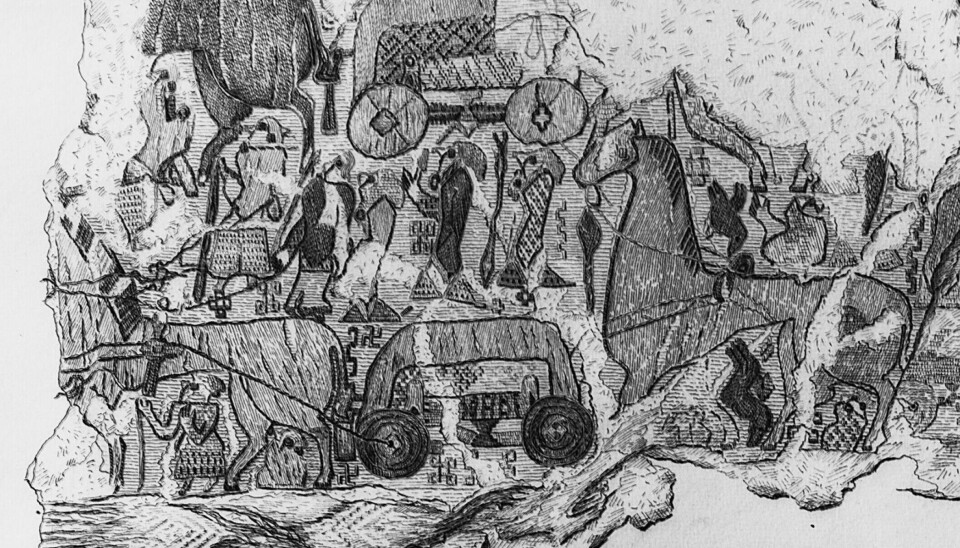

The tapestries depict a variety of scenes. Some show processions of wagons and people, others depicts battles, and some illustrate rows of people moving from right to left.

The best-preserved section

The most intact tapestry fragment depicts several wagons, horses, and people.

“They’re holding unusual items. One is carrying a staff, and another might be holding a lamp. The wagons are adorned with intricate patterns, possibly textiles,” says Vedeler.

This could offer a direct glimpse of what a procession of wagons and people looked like – captured in a tapestry likely made in the 9th century. Some of these tapestries might have been locally produced, serving as a kind of testimony from a specific time and place.

“Many have examined the garments depicted and compared them to those shown on gold foil figures,” she says.

You can read more about gold foil figures on sciencenorway.no.

Vedeler notes that all the women depicted in the Oseberg tapestries have a type of train on their dresses.

“This was a status symbol,” she says.

Some of the women are shown wielding swords, depicted in battle with shields, yet they still wear these dresses with trains.

“That must have been impractical,” she adds.

What about the most damaged fragments?

Many of the tapestry fragments are so deteriorated and small that they are difficult to interpret, especially in terms of how they fit together.

Or what story they are really telling.

“We’re hoping to see if these scenes can be assembled into larger narratives,” says Vedeler.

An ongoing research project, called TexRec, is exploring whether artificial intelligence can be used to automatically piece the fragments together and identify which ones match.

Can computers solve the puzzle?

Davit Gigilashvili, a postdoctoral researcher at NTNU’s Department of Computer Science, is part of a team developing software to piece together the tapestry fragments into larger images.

Gigilashvili believes that computers can be trained to group fragments.

“Algorithms can learn to recognise different styles and motifs. For example, human silhouettes might resemble one another, or two figures may look like warriors, indicating that the fragments could belong to the same battle scene,” he says.

Machines could also potentially be trained to identify similarities in weaving techniques, such as the number of threads per centimetre, allowing the fragments to be grouped that way.

However, Gigilashvili says it is unlikely that computers will be able to automatically solve the entire puzzle.

“These fragments lack so much information that current methods just aren’t advanced enough,” he says.

The pieces are damaged, they don't fit together properly, and significant expertise is required to understand how they connect. Computers are also not particularly good at solving traditional puzzles.

Additionally, there’s the issue of training data. While large AI image models are trained on millions of images, no such data exists for ancient, unique woven archaeological textiles.

“Image AI learns patterns based on millions of images, like recognising what a bike or a human face looks like,” he says. “We’ve had suggestions to create woven textiles and artificially age them to simulate wear and tear.”

In theory, this could be used to train the machines, but the process is expensive and difficult, according to Gigilashvili.

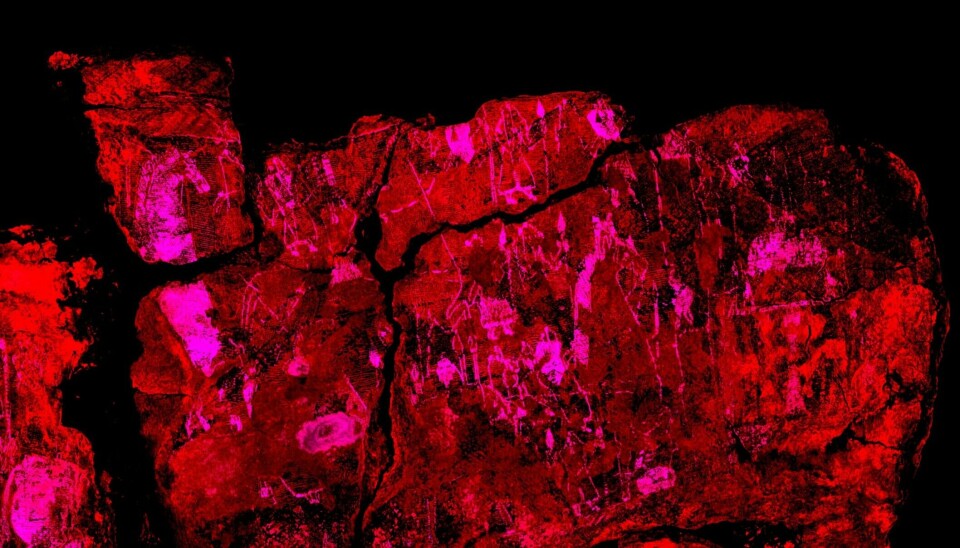

But they have found a way to reveal details

So far, the project has developed software that treats the fragments like puzzle pieces, allowing researchers to see how they might fit together, rotate them, or compare them.

“We can also adjust contrast or manipulate colours to bring out details that are difficult to see. Certain colour filters can make the remaining details in the images visible to the naked eye,” says Gigilashvili.

The fragments are set to be exhibited at the new Viking Ship Museum once it’s finished, but Marianne Vedeler hopes to uncover more before then.

“What I would really like to know more about is which pieces belong together, and what complete stories do they tell? Can we piece together a more cohesive narrative?” she asks.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no